Viewed 14880 times | words: 8812

Published on 2020-06-14 21:24:22 | words: 8812

As the title says, this article is about "scenarios".

And it is about unbundling, i.e. "unpacking"- both scenarios, and the three "industries" that I selected for this post.

Anyway, the next few sections will be focused on the first part of the title, i.e. The post-COVID economy, as will serve to outline the context of any scenario-based discussion:

- The difference between scenarios, forecasts, and plans

- The communication side of unpopular choices

- Managing crises and risks in Italy

- Allocating resources and re-inventing government

- The alienation effect of realistic assessments

The difference between scenarios, forecasts, and plans

I discussed few days ago a theme that recent discussions on the "performance" of epidimiological models visualized.

A scenario isn't a crystal ball affair.

Actually, in many cases (e.g. counter-terrorism, business activities to pre-empt risk and adverse events)...

...the purpose is not to prepare for what cannot be avoided, but to spur into action- to actually prevent what your model shows.

In all these cases, there must be at least two elements:

- an assessment, including information on the context, what I could call the "Pavlovian side" of societies and organization (i.e. a foreseeable reactive answer to a set of stronger or weaker "nudge" initiatives)

- a chain of events, with degrees of freedom and constraints/weaknesses/etc, so that potentially such a chain can be altered.

Example: if you allocate resources to counter-terrorism and no terrorist attack succeeds thanks to the ensuing actions, your scenarios on potential impacts will (hopefully) never deliver the expected damages.

So, you will be asked to answer for a negative: having explained the risks, having outlined the potential impacts, having helped carry out actions to pre-empt any of that from happening...

...the question becomes not "how and why we were successful in preventing a bleak future", but "why did we allocate resources or generated indirect costs, while nothing happened"?

The communication side of unpopular choices

As you can clearly understand, this is more a matter of communication management (from all the parties involved, plus toward the external audiences), than of misalignment of purposes or lack of knowledge.

Let just say that, with COVID-19, fear affected the communication abilities of too many: scientists, politicians, business decision-makers, and the audience(s).

Why audience(s)? Because there were different types of audiences, at the beginning, and with different levels of ability to influence events.

In the end, all were involved at a personal level, but at the beginning the first three had a disproportionate potential impact.

Impact that extended both on the course of events and the perception by audiences.

One of the courses on COVID-19 that I followed was delivered by the Imperial College on Coursera and, as I wrote online before, one of the interesting elements it contained was a routine update video interview, that, over the course of few months, showed how much knowledge of COVID-19 evolved.

Until early March, at least in Italy, there was aggregated resistance to any containment measure, with plenty of exchanges to "avoid generating panic" and "underestimating the risks", which usually resulted in asking others to make choices.

In Italy, there is an ongoing legal squabble about who shold have made which choice but, in reality, the point is different, and only one politician dared to say it (also because he is only marginally affected by any allocation of responsibility).

The reality?

Frankly, despite all those who say that, since decades, we live in a "risk society" (not just in Italy), we don't.

Just to rephrase what we are dealing with: we just passed the first wave of a new epidemic, and our current technology enabled us to contain it better than what happened in 1918.

As reminded few days ago by President Macron and Chancellor Merkel, we should use the lessons learned in this phase to improve our preparedness for the potential second wave.

Shared on Facebook few days ago: an #interview with #Fauci on the #forthcoming #second #wave of #COVID19 : while #President #Macron and #Chancellor #Merkel warn about #preparedness, in #Italy we seem almost onto the usual "passata la festa, gabbato lo santo"

better to remember,, before somebody starts dismantling all the work done over the last few months to improve the posture of our #health #system: it is not yet time of writing a book on "lessons learned"...

Actually, also for other crises that might happen down the road- from further viruses, to economic crises, to the side-effects of massive relocations due to global warming and other issues: as reminded within an old book Teggart's "Rome and China: a study of correlations in historical events", it wouldn't be the first time that the dislocation of a population provokes ripple-effects across the known globe.

Also, it should be considered what could happen in a second (or third wave) this is from the CDC website

"It is estimated that about 500 million people or one-third of the world's population became infected with this virus. The number of deaths was estimated to be at least 50 million worldwide with about 675,000 occurring in the United States. Mortality was high in people younger than 5 years old, 20-40 years old, and 65 years and older. The high mortality in healthy people, including those in the 20-40 year age group, was a unique feature of this pandemic."

Managing crises and risks in Italy

Our societies, notably in relationship-based societies (such as Italy), haven't yet developed a cultural and operational framework for risk.

In Italy, usually we have plenty of laws, decrees, regulations, but we are used to "adjustments", as I wrote often.

This implies that decision-making requires, more often than not, a joint exercise of bartering and "balancing", as if we were to strictly look at the letter, we could end up chasing our own tail for a while.

So, we have to build up momentum for any unpalatable choices that could affect in an unbalanced way our tribes.

You probably read about the Caravanserail of committees that since early March (but, actually, before) appeared in Italy.

Yes, COVID-19 and its response were part of the reason.

But, actually, in most cases what I read and heard is "recycled" material from previous position papers- as I wrote in recent articles, "coronadressing" is tempting, as enables to push your agenda while wrapping within the emergency bandwagon.

And this happened at the national, local, private, public level...

You know that I have been writing for a long time how Italy has been falling behind its European partners since at least a couple of decade.

My observation is based on statistics,yes- but also, more importantly, on "on the ground" observations while working around Europe since the late 1980s.

I saw this falling behind as a side-effect of the inability of the country to develop a systemic view- we are still partitioned into countless tribes, tribes whose interest converge when resources are lavishly available, but instead, when resources are scarce or "prioritization" is the mantra...

...it is a continuous re-assessment of power balance.

To avoid repeating what you can read in tens of thousands of words just since early 2020: convergence or agreement is routinely achieved as a convergence of interests, but no agreement is ever final, well before it is implemented, as all those involved continuously monitor and assess any potential, immediate, or foreseeable, re-balancing that could affect their position either positively or negatively.

Side-effect: we talk about long-term plan, but live in a constant state of flux- you do not simply look for a new potential opportunity where you could get a better hand now that the balance is either changing, or going to change...

...the tradition is to renegotiate (something that my foreign contacts working in Italy told me since the 1980s- sometimes with unusual results).

And this COVID-19 crisis, and the ensuing constantly increasing allocation of funds, is no exception.

Allocating resources and re-inventing government

If you are old enough, you probably know that "re-inventing the government" was a 1990s initiative (I shared some commentary and related experiences in past writings).

Let's just say that, in reality, digital transformation is a often used as a way to push through cultural changes that are much overdue.

Notably in a country such as Italy, were we live in the XXI century and expect XXI century services, but then behave (as individuals and a society) as if it were just a matter of personal goodwill.

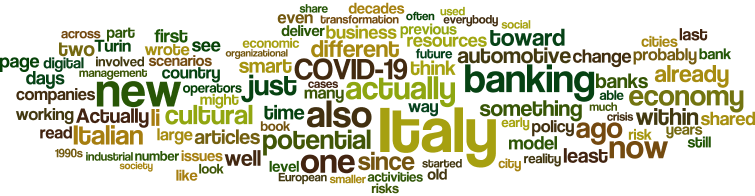

This is the status of the Italian economy, shared online between June 8th and June 10th:

#news from #Italy - the #present of the #economy

- #impact of #COVID19 #recession is uneven

- #ABI (bankers' association) issues new rules to ensure #COVID19 funding to be released to #companies

- #steel #production : #Ilva #Mittal as the last drop

I will share immediately my thoughts on the latest initiative, the "Stati Generali".

Here are the news that I shared on Monday:

#Italy #Stati #Generali 1: #background- how the GDP is composed, and an article from #Ainis about the usual routine- multiplying power and competence centres...

#Italy #Stati #Generali 2: event management and alignment between #economic #policy and #social #reality

It was announced and supposed to start on Monday; then was supposed to start Wednesday, then Thursday, and now, for external reasons, started yesterday, Saturday.

Its duration was to be initially few days, then stretched into ten day.

As of Friday evening, the full agenda and the invitations weren't yet formalized, but a discussion was repeatedly presented into first a plan for what had already been identified or allocated (e.g. by the Decreto Rilancio, as well as the European Union initiatives), then something more ambitious.

Aims? The more are clarified, the more sound akin to developing in days what hadn't be developed in decades.

I think that what at most can deliver is either something that in reality had already been prepared, or a general framework that then, dialectically, will be the "umbrella" for whatever will be actually done later.

Or a mix of the two- also because, while the centre-right opposition decided not to attend, members of the coalition eventually started saying that they too will present proposals: if it is a political platform, everybody wants to share it...

The loftier the goal, the shorter the time and resources allocated to it- is a national habit.

So, I am pragmatically skeptical (maybe because, not at the national level, and mainly in business, I have been involved in attending, organizing, converting discussions from workshops on various subjects into action since the 1980s).

But I can see, as usual Pollyanna-style, a potential positive: for a long time I wasn't the only one advocating a serious discussion to define a new industrial policy.

Look e.g. at my most read post on this site Per una politica industriale che veda oltre le prossime elezioni #industry40 #GDPR #cybersecurity / For an industrial policy that survives election cycles #industry40 #GDPR #cybersecurity.

So, why has been Italy unable to design and implement an industrial policy that wasn't just a set of "adjustments" (what in Italian are called "pannicelli caldi"), for few decades?

The alienation effect of realistic assessments

As I said a couple of days ago while discussing with a friend, I think that we keep having issues with the analyses and assessment prepared by our gazillion of think tanks.

Not because their lack of skills or capabilities, but due to cultural issues.

The trouble is that, in Italy, the above mentioned "fluidity" implies that even the best analysts routinely do not say what they would like to say according to their findings, as this could be "future relationships damaging".

The interesting part is that this is not even by design (albeit in some cases is): it is a Pavlovian reflex- "talking straight" in Italian is considered not polite even when you are an analyst- hence, it is a back-covering exercise.

Meaning: you do your analysis as should be done; then present what is as close as possible but nuanced enough for relationship sake, and, if at a later stage, somebody complains that you didn't say what should have said, you can point to some paragraphs here and there that, if connected, could clearly show your argument.

Talking straight is what, when I had some "experts" delivering me advice, wanted.

More than once had to clearly state in Italy that I wanted clear information on status, trends, risks- then, how to communicate them was my task: if the experts go "politically correct", everybody will go as far as possible from reality, and as close as possible toward cocooning.

Earlier this week I was reminded how I said last year, well before the COVID-19, that we were heading into a situation that could at last push us toward making choices (e.g. in Italy everybody talks about digital transformation because it is trendy, but then we retain highly-hierarchical decision-making approaches following the mantra "nothing that affects negatively our tribe").

Well, the chaotic management of this current "thinking-planning-assessing-budgeting" phase (yes, in that quixotic order, jumping back-and-forth on an infra-daily basis) should at last stir the (money) pot.

My assessment? It is an opportunity, if seized at its peak (i.e. before a tribal re-assessment intervenes).

Specifically, it is an opportunity to have a meaningful debate and then start the real design work.

That will not last just two, or three, or even ten days: it should be considered a "kick-starting" or "scope definition" workshop.

Otherwise, as I wrote in previous articles, the amounts involved (both new debt and the EU resources) risk becoming something that will negate any possibility of changing course for at least a couple of legislatures, if the wrong course is chosen, and, as we, as "sistema Italia" (Italy at the systemic level) already lost at least a couple of decades, this would mean skipping a generation (social- and business-wise), and probably affecting one-two generations more.

So, "where are we now"? I think that what I posted two days ago on my LibraryThing profile, information from a book on Turin I read few days ago, actually summarizes points that I already discussed here since 2012 (and elsewhere online since 2003).

You can read the review of "Chi ha fermato Torino" here.

If you prefer something lighter (albeit the book is only slighly over 100 pages long), today, as part of my German language skills improvement path, watched in German a movie that is probably worth showing to anybody who is confused between means and purpose: "The Bridge on the River Kwai".

What's behind the title

Within the previous sections I shared a short summary of a complex environment (Italy), an environment where, as I keep repeating, a week could deliver as many twists as an ecological era in another country.

As an example, slightly over a week ago a poll stated that now we shifted toward four main political parties, each between high tens and low twenties (in %), and few days later... we were back to three main political parties.

Today, in a new poll we were to two blocks, both at roughly around 40-42% each, with a single party going up above the planned 5% threshold, and an asteroid belt of tiny parties, all well below 5%.

Even more interesting, one party within each potential coalition is scheduled to grow organically in part by absorbing votes from the other party (actually, in one case the poll identified a potential third party in a coalition that would take votes away from the other partners).

If you are curious: posted in Italian, but added also one of my routine NOTAM in English.

Search for "leader" within this site (it catches also leadership etc), and you will see a long list of articles, book reviews, etc.

If you know a bit about Italian history, at least XX century political history, you can understand why.

Italy is a complex country that doesn't like complexity, and therefore, routinely, instead of reforming, we look for shorcuts.

One of this shortcuts is a quest for a leader, as if one person could be enough for the governance of a country where tribal interests generally trump common interest.

When trying to quickly do what we hadn't be able to do in decades, this instinct becomes even stronger- and my foreign readers probably remember all the enthusiasm about Mario Monti almost a decade ago, then turned into politics as usual.

To streamline, have a look just at few articles, one per year 2015-2019, covering both leadership and defining an industrial policy:

- 2015

- Miopia culturale e politica industriale in #Italia

- 2016

- Amministrative 2016-03 "io sono quello che ha pagato i conti"

- 2017

- il paese dei leader (in 2019 updated as Il paese dei leader / The leaders' country takes a page from Vichy

- 2018

- Per una politica industriale che veda oltre le prossime elezioni #industry40 #GDPR #cybersecurity / For an industrial policy that survives election cycles #industry40 #GDPR #cybersecurity

- 2019

- From #Mattei to #MES / #ESM - #Europe and #Italy

If you look at all the articles within the Business: rethinking section, there is a concept, rephrased in various ways, that appears often: disintermediation.

Why unbundling

The idea should be familiar: technology, social and business evolution- all converged to enable nimbler new operators to "skip" one or more layers within the market, to deliver services and products that previously involved various (and probably larger) operators.

Decades ago, automotive, banks, cities (at least in Italy) where doing everything "in house": from producing your own steel for your own cars, to printing and delivering your own monthly statements if you were a bank, to managing water, trash collection, etc if you were a city.

Then, supposedly in the name of "competition", we started unbundling industries.

It might have been separating the management of an infrastructure from its operation and its use (e.g. in telecom, trains, electricity).

Personally, as I worked as a supplier and in outsourcing practically since 1986, I have been on both sides in many industries, and shared already almost two decades ago some feed-back on potential issues (reprinted and updated in 2013).

What did COVID-19 was to actually compound with existing trends.

Disintermediation is part of the "uberization" concept, in a way, i.e. being able to deliver a product or service without having the assets needed to design, develop, produce, maybe even distribute.

So, despite all the standards, compliance, etc, now it is feasible to have "niche" car producers or new financial operators that actually have to respectively use suppliers or have agreements with "traditional" universal banks.

Actually, new car producers such as Tesla had to "import" talent to be able to scale up production- but, in the future, probably volume will be less important than value-added.

Incidentally: "talent" doesn't necessarily mean people- also "representation of talent" (books, videos, etc) can convey useful information- albeit, often, optimizing requires somebody who already connected those dots, as any "formal transfer of knowledge" tries to (re)structure knowledge.

Therefore, what will matter is the ability to integrate into new products (physical, financial) "components" available on the market.

And that is where, frankly, "old" companies still have a competitive advantage.

Actually, whenever I talked to start-ups within the automotive and banking domains in Italy, I found that, behind the founders, the expertise came from established players.

Actually, in some cases, I think that actually "spawning" new, nimbler operators is going to be the common choice for many established "giants".

Technology (automation, AI, etc) and new socio-economical trends (more about this later) will change models of ownership and consumption much more than we are used to now.

Social and cultural change, courtesy of COVID-19

No, I am not going to talk about remote working, or social distancing, or reduced travel.

Courtesy of COVID-19, change is actually happening faster than most organizational cultures are ready to- notably in Italy, where, as I often repeated, one of the reasons why "cuts" were mainly horizontal (a whole layer, without really that much assessment) simply because tribal links, and exchanges between tribes, made next to impossible to avoid ripple-effects.

So, Draconian changes are routinely adopted as the way ahead.

The same applies to city design.

Urbanization is a trend that, until recently, was considered a destiny shared worldwide.

This generated few issues as, e.g. in countries such as Italy, urbanization used to be coupled with development, a more affluent society.

Since at least a couple of decades, this wasn't true.

As an example, if you look at the book review about Turin that I listed above, you will see a reference to an article from 2016, "io sono quello che ha pagato i conti".

Turin was already into a decline well before 2016, and the debt assumed for the previous wave of urban development didn't deliver enough results to justify those investments.

Actually, well before COVID-19, the issue for towns such as Turin was: who will finance a "smart city", if the shift from a manufacturing economy toward a service economy wasn't based on high-value-added jobs, but on what was increasingly becoming a "gig economy", even for activities that in other countries are "ordinary" jobs?

Is a "smart city" built for over 1.4mln people, now reduced to less than 900,000 inhabitants, still sustainable, with the current (pre-COVID-19) socio-economic environment?

Are we heading toward "smart cities" that look like Mitchell's "Reinventing the Automobile: Personal Urban Mobility for the 21st Century (MIT Press)" (a kind of update of Womack's 1990s "The Machine that Changed the World")?

Or toward huge urban centres à la "Blade Runner"?

Over the last few years, while I was living in Turin (November 2015 - February 2019), attended few meetings about the design of the new "town master plan".

Well, as I shared on Facebook a newspaper article: as I discussed two days ago, #COVID19 is actually acting as a fig leaf for a #trend toward a different kind of #urbanization

a new #Middle #Age with each #smartcity for fewer surrounded by connected yet distant suburbs and villages.

still looking to become a town integrated within a region

call it the #Trantor #urban #model (from Asimov)?

Bear in mind that, even before I started living and working again in Turin (2012), I was already saying (and then writing) that I could not see as sustainable a town that had been expanding (and preparing to add more expansions) while its population contracted, and, moreover, the "shift to a service economy" wasn't the one you expected- with a shrinking tax-revenue base.

So, I am not against the quest to contract by few million meters (approx. 10%)- I am against the social engineering trends that I saw since 2012.

The idea? As I discussed with a friend, while many talks about a "nuovo umanesimo", some of the discussions that I heard while in Turin were closer to a new castle-based society, where the "castle" is our forthcoming smart city.

With the excuse of COVID-19, an attempt to go back toward a pre-industrial economy, where a town-castle is for few and those supporting them.

Instead of 60-70% of urban population, maybe 30% that consumes as if it were 60%.

All the others, go outside, and need to find ways to keep them out.

Almost as the famous NATO joke about keeping somebody down, somebody in, and somebody out.

Because having all these masses within urban centres under a glass ceiling is an issue.

Somebody say that smart cities of the future will be an example of what in the fascist past of Italy was called "autarchia": self-producing everything.

Well, for the time being, both produce and energy as well as products will have to come from outside (albeit, as others and I wrote since years, 3D printing and automation could actually enable "clean" micro-factories also in towns).

More down-to-Earth, Italian newspapers over the last few years routinely published articles that invited e.g. those with university degrees to return to a pre-industrial time.

Such as to inhabit villages that have been abandoned post-WWII, back then to fuel the industrial development of the country- but not to use their skills there (feasible, in the XXI century), but to revive lost skills, jobs, productions.

Forgetting what I was told a couple of decades ago from an old man living in the mountains.

The "old way" was a subsistence economy, nothing close to what city-dwellers were used to.

When in the 1950s-1960s companies started looking for factory workers, many in the mountains run for it, as working 8 hours, having running water and electricity, and all the other "city life things" (movie theatres, shops, etc) were a much easier life than raising cattle or growing produce in the mountains.

Personally, I think that, in a service economy based on human capital to deliver added value (as most routine manual activities will eventually require less and less people), there could be a place for reusing villages in a different, more modern, more connected way.

Not just to produce what is consumed by the smart cities of the few.

What Italian newspapers and magazine were actually offering was something else: keep getting a degree for your own personal interest and education, but then get away from towns, and get back to what was done by our ancestors.

Obviously: journalists and upper class, as well as politicians and their tributaries, would still stay in less crowded, more human, more enjoyable "smart cities".

As I was told two decades ago in Turin: the game is up, there isn't enough for everybody, and this was well before reading a 2009 automotive marketing book describing the Italian market as following "the hourglass model".

A different kind of hourglass, where the bottom half stays there.

Despite what some say of my background, since the 1980s I keep repeating that I think that with the Republic "titles" ceased to be differentiators- and this should apply also to lineage etc.

Actually, in the XXI century (I know, I write this almost in every post) automation coupled with disintermediation and a data-centric society mean that we need something else.

Every individual citizen might have to contribute new ideas, concepts, innovations, no matter the "status" (or even degrees, titles, age, etc)- both as an individual choice, or as a side-effect of interacting with the new "smart environment".

In my view, "smart cities", if you adopt the "urban dissemination" model, enable to create "smart villages" and "smart virtual cities" (e.g. administrative units that are physically separated, but aggregated along different lines).

I know that, as usual, "pushing away to villages" and creating again a "castle" mentality would appeal to many (actually, those who will not be so "pushed"), following the Italian saying "lontano dagli occhi, lontano dal cuore".

And, again, apparently a way to simplify complex choices.

Anyway, that would be both a waste of resources, and just procrastination- and in Turin and elsewhere in Italy we are where we are now as a side-effect of "working along the line of least resistance".

If you reposition issues, they do not get solved- actually, may expand, as a cancer.

There will be time in the future to discuss more about "socio-economic models"- and, as I wrote above, I think that all is converging now toward generating a potential critical mass for real change.

If we fail now, worst case scenario is that what we saw recently, multinationals keeping in Italy just their "service" and "selling" part, will increase: a consumption country.

Anyway, before developing scenarios, I would like to see what will be produced by the next ten days of talking and negotiations called "Stati Generali".

Furthermore, before choosing either my model of "smartcity" or the other one, we will have a transition phase.

A transition that already started few years ago.

Transitioning economyic models in Europe, phase 2

Well, people of my age would probably reminding something, by reading the title of this section.

The first wave of transition economies included those that used to belong to the COMECON.

Think about it: when you read about "need to change economic model", "things will never be the same again", "moving toward a green, digital, inclusive economy"...

...you are actually saying something that, in XXI lingo, echoes a bit the promises of the "Communism is Soviet government plus the electrification of the whole country".

Then, beside the unification of Germany, that took a while to be politically "a new normal" (an Italian politician said once "we like Germany so much, that we like to have two of them"), former COMECON countries had to redesign themselves, to adapt before they could become full members of what was to become our current EU27.

As for the 28th member, UK: the COVID-19 side-effect announced today pointed to a -20.4% GDP loss in April, vs. -5.8% in March.

Actually, I lived both seasons, as I was in Germany for personal reasons in the early 1990s, and then in Baltic countries in the late 1990s.

Changes weren't trivial, most of all cultural and organizational changes.

You can change laws by fiat (or by a vote of Parliament), but implementing them is another ball game.

As I reminded few times in the past, in early May 1993 went in Prague, and it was funny to read on a local English-language newspaper advice for foreigners that said something on these lines: private property and associated contracts are something new; therefore, after signing a contract, re-read it with the other party, as otherwise you risk ending up as that foreigner who signed a contract for a property, and then discovered that the owner assumed that he could still use it (well, it happened also in Turin, so I would say that cultural change maybe takes a while).

What we are talking now about is yet another transition.

I shared in previous articles data on the forecasted impact of digital transformation and AI on automotive and banking, and also electrification of cars, smart cities, moving toward a greener economy, etc.

As reminded earlier this week by the European Central Bank (I will quote material that I read today as part of my weekly update for the ECBSpeech webapp), changes already started.

Example: "Further decline - by 6.3% on average - in number of bank branches in most EU Member States

And, as remarked on June 10th by Isabel Schnabel, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at an online seminar hosted by the Florence School of Banking & Finance: "First, some sectors of the economy may never return to their previous size, requiring a large reallocation of capital and labour, also across borders. Despite some progress in recent years, however, product and labour markets in the euro area still remain too rigid to accommodate the required shift in resources in a swift manner, risking permanent damage to the economy.

Second, the speed and extent of capital and labour reallocation is likely to differ across euro area economies, depending on the sectoral composition and the quality of labour market institutions. Such differences, if left unaddressed, risk increasing heterogeneity and fragmentation, further complicating the conduct of the common monetary policy.

Third, recent events have increased the odds that large cash-rich firms may absorb liquidity-strapped start-ups, thereby curtailing competition, with potentially adverse effects on productivity and welfare. The pandemic could therefore amplify trends in economic concentration that we have already observed prior to the crisis, particularly in the United States.

Fourth, there are risks that COVID-19 will lead to a surge in protectionism reversing the current pattern of international production. While re-shoring could be the outcome of benign advances in automation, a general unwinding of global supply chains would jeopardise potential output growth across the globe.

And, finally, financial distress of firms and households will cause the share of banks' non-performing loans (NPLs) to rise over time, weighing on bank capital and potentially clogging the bank lending channel of monetary policy.

" (from The ECB's policy in the COVID-19 crisis - a medium-term perspective).

So, COVID-19 might accelerate (and not just in banking) a concentration- further reducing competition.

And this bring me to discuss last two specific Italian cases.

As, I think, both represent quite well what our transition accelerated by COVID-19 might generate- across all industries.

Expanding or removing potential competition?

As I wrote above, "unbundling" could actually expand the power of those organizations that have a longer and deeper industry experience, as shown the share of total assets.

In both automotive and banking, Italy is currently looking toward another round of concentration.

I will first talk about banking, as it is (for now) an "Italo-Italian" (as my French friends and colleagues used to say in Paris about "Franco-French") affair.

When I was working in the first banking project, a general ledger in 1987-1988, the number of Italian banks was on 3 zeros- now it is much smaller, but still we have what many call "too many, too small".

There are now two main Italian banks, Intesa Sanpaolo and Unicredit, and both grew through acquisition and mergers, mainly since the 1990s.

Why back then? Because there was a major reform in banking ownership, spawning banking foundations that are now a major player within the Italian economy, notably on social development; few days ago posted a review of a book published recently: Tombari-Greco - Fondazioni 3.0: Da banchieri a motori di un nuovo sviluppo - ISBN 9788830101326.

Intesa Sanpaolo launched an offer for Ubi, a smaller player that it would like to absorb, after selling to another player (trying to avoid anti-trust objections) part of the branches.

Across my business activities since 1986, I was involved in cultural, organizational, technological change activities before, during, and after a Merger&Acquisition (M&A) activities, with various roles.

The banking industry was the first one I worked in that had a large compliance side, well before this extended to other industries (from ISO9000, to SOX, AML, etc.)

Nowadays, compliance is the "great cultural equalizer"- at least on the operational level.

Still, in my experience, there are plenty of cultural differences between banks, and also within banks.

In Italy, in meetings, early in my career was able to differentiate those who were "bancari"-bank employees, from those with a family background as "banchieri"-bank owner, also if they have the same job title in different banks.

Why this "cultural digression"? As noted above, the current economic climate risks negatively affecting the availability of competition.

I wrote already in past articles that I think that the number of branches will keep contracting.

What I do expect is actually a "reshuffling" (see previous articles).

If we sideline for now which shape will take "smart cities" (i.e. "Blade Runner" or "castle"), there is a common thread: no more private car for everybody, banking branch for everybody but a different offer.

Personally, I switched to "electronic" (home banking, remote banking, etc) whenever available, in whatever country I was living and working in.

Actually, since the early 1990s I almost never visited a branch (except when "going electronic" wasn't an option).

In the future, backbone banking services and products will need a critical mass that mini-banks of the future will not have.

Therefore, when e.g. I will obtain funding from you via a platform that maybe belongs to Intesa Sanpaolo, Unicredit, or new operators, I can then add my value added as mini-bank, by building up services, that you megabank cannot deliver as fast as a mini-bank can.

Why? With automation also of decision-making processes that are really based on "parameters", a large bank still has the issue of a large organization to disseminate information on new products and services, as well as monitoring.

And this takes time.

A smaller, purpose-built operator, could instead assemble a new product or service just for a single event, and rely, for its "technical" (payment systems, compliance, etc) components, on the "menu" (toolbox) of options offered by larger entities.

Actually, as discussed above, generating these "single-purpose mini-banks/financial operators" might be a way to "teach the elephant to dance" (to use an old consulting buzzword), i.e. enable a long-standing banking behemoth to behave as a startup.

But this is the end point.

In this transition, in banking (as we will see later, also in automotive), the game might be different.

If the purpose for Intesa Sanpaolo were to increase presence in territories, probably scooping up smaller banks that have some issues could be the "old" way (in the past, Bank of Italy and the Italian Bankers' Association had larger banks buy smaller banks that had some issues: I remember e.g. Banca Fabbrocini, Banco di Sicilia, Banco di Napoli, etc).

But integrating a large number of smaller companies implies having to deal with plenty of cultures to integrate.

Instead, a faster approach is removing from the market a potential competitor large enough to plan to eventually create and offer on the market a competing platform.

Actually: a medium-sized bank might be better positioned to "grow in the new way", i.e. by creating a platform, and then offering it to smaller operators, instead of trying to grow organically (it is an approach that, with some differences, saw in the pre-Internet era in both Belgium and Italy, in banking).

Also, a medium-sized bank would be potentially just one culture to integrate.

If this post were to be about cultural change, I would discusse case stories that I collected across Europe on M&A in banking, from people working within the banking industry- but this is not.

Now, before talking about common elements, I will shift to another industry, automotive.

In this case, everybody is criticizing Renault that is cutting workforce because the model of Ghosn was wrong- which was similar to the one that had for FCA Marchionne, i.e. volume growth.

Actually, it is funny as right now technology enables to do something that was within the 1990s Womack's "The Machine that Changed the World", e.g. producing in large factories what are basically unique cars.

In reality, the point isn't volume growth, if volumes will contract.

Is about purchasing quota, as did in steel Mittal.

To remove competitors and control offer, but also remove competing cultures and expanding your own.

Building up volume now is actually akin to "retiring capacity"- critical mass to be able to provide efficiently the "Lego bricks" needed to deliver a new car model.

Already in the late 1980s I saw how some structural elements (chassis) were shared between nominal competitors, as the investment needed to create a new one was too high.

If they aggregate and have a higher volume, they can improve efficiency and push out competitors that cannot share across the volume, so that, when volumes will contract, there will be fewer able to survive, and able to define the offer, systemic integration, etc.

Specifically on the Renault cuts, it is a déjà-vu: when a new top management team arrives, the outgoing team clears up the desk (and enforces the cuts) that the incoming team would need, so that the one incoming can claim to be building, instead of having to deal first with the unrest for the cuts due to the failure of the prior model

It is a culture that I dislike, as it doesn't build a clear line of accountability and "imprinting": I rather follow the one that I saw e.g. when in the early 2000s, after Marchionne entered, I was told that he was cutting 40-50 managers a month, to flatten the structure.

Of the two elements, "imprinting" is more important: if you restructure the activities while being inside (also with zero impact on the size of the workforce), you are the one who defines the cultural elements to be retained or promoted, and those to be phased out- according to your criteria of where you are heading to.

If you let that task to the outgoing management, they will follow their own parameters, or their assumptions about your parameters- and maybe will introduce some additional cultural, organizational, technological side-effects that you will have to deal with.

Why? because you have to ensure that it is your model that is enforced- and that your cutting choice are done, as when cuts are widespread, usually there is also a "corporate politics" element- and you risk tossing away human capital that would be relevant to your business model.

Their core business isn't to make cars, already externalized long ago, their core busines is how to do a car, how to integrate systems, how to distribute and support cars.

Albeit some of those activities shifted already at least partially to their suppliers, e.g. Bosch and others.

The "new automotive industry" already few years ago in Germany was forecasted with a potential losse of 200,000+ high-value-added jobs.

Also in recent reports stating the increase of jobs in USA, I say: look at the figures, at the mix- not at the number of jobs

So, for competition sake, I would rather see a third operator in banking in Italy, to differentiate offer and "scale up" in a different way.

But I think that it would make sense to have a merger of automotive companies across Europe coupled with parameters to ensure an eventual "unbundling", as it was done e.g. for the energy industry.

Anyway, antitrust is revising both banking and automotive merger and acquisitions, e.g. Intesa-UBI and FCA-PSA.

From an Italian perspective, the merger might be FCA-PSA, but from what has been seen so far, sounds more like an acquisition by PSA of FCA.

Conclusions

While waiting for the end of "Stati Generali", critical is to have transformation considered not as a change of business models, but of the underlying logic on workforce buildup and related objectives.

Such a logic should be defined from the top, i.e. from society as a whole: it is a political issue (and, in my view, politics includes also social and economic operators).

In both manufacturing and finance, we have a scale factor that has cultural impacts in Italy.

E.g. in representing instances, also within business, the number matters more than the size/culture mix: having a large number of small companies implies that their viewpoint is potentially better represented by industrialists' association than that of larger companies- notably when there is a crisis.

The decision-making timeframe of a small company isn't that of a multinational.

Hence, it made sense the initial choice of Marchionne to leave the industrialists' association: what has to do FCA with tens of thousands of companies that barely get into a three digits workforce? Culturally, and by investment and management logic, they are on a different scale and mindset.

A representativity weighted on cultural and organizational capability would be needed, if a single voice is to be heard to build up the future, and not just struggle to ensure business continuity of a fading status quo ante COVID-19, ante digital transformation.

But I wrote in the past both in articles, books, and on Linkedin about the need for a cultural growth: in the next phase of industrialization, companies will probably have to get used to bridge their organizational culture differences, and actually to learn how to work with different corporate cultures on different supply chains- even small companies.

Italy often misses opportunities not because the human or financial capital aren't available, but because there is a "tribal mismatch".

So, I find boring our obsession for "capitani coraggiosi" working for free and making damages (see the references about "leader" and "industrial policy" shared above).

Equally boring the routine newspaper articles that, whenever there is a success abroad, dig and find a prior application (or suggestion) in Italy: ask yourself why did it die here- as I wrote often "capacità progettuale" does not imply "capacità di eseguire i progetti".

And now, let's wait to see if the convergence of this crisis and a large amount of resources in a short time will help decision-makers to think long-term.

To close down, I would like to share few items presented by Christine Lagarde on June 8th, to the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs of the European Parliament (I selected few paragraphs): "The COVID-19 pandemic and measures to contain the spread of the virus have caused an unprecedented contraction of economic activity in the euro area.

After a contraction in GDP of 3.8% in the first quarter of the year, our new staff projections see it shrinking by 13% in the second quarter. Despite being expected to bounce back later in the year and recover some of its lost ground, euro area real GDP is now projected to fall by 8.7% over the whole of 2020, followed by growth of 5.2% in 2021 and 3.3% in 2022.

The European Commission's proposal for a revised Multiannual Financial Framework and the Next Generation EU are decisive in this regard. And we should not forget that the largest supranational issuance in euro ever announced that is associated with the proposal could also have a positive impact on the international role of the euro.

It will be important to adopt this package quickly. Setting a clear timeline will give more certainty and confidence to citizens, businesses and financial markets. Any delay risks generating negative spillovers and driving up the costs, and hence the financing needs, of this crisis.

European spending will be most effective if its focus is on projects that add real value from a European perspective.

The primary common interest is to reduce the fragmentation stemming from the present crisis and divergence in the longer run.

Another key dimension is the digital transformation. Here, the recent lockdowns have accelerated the adoption of digital technologies on a broader basis. Now is the time to expedite the digital transformation on a more permanent basis and bring the EU to the frontier of the digital economy.

If combined with appropriate reforms at the national level, these measures will strengthen economic resilience and boost our economies." (full text here)

_

_