Viewed 18229 times | words: 3259

Published on 2019-12-09 13:21:48 | words: 3259

Yesterday I shared a commentary on the current cognitive dissonance between our political leadership (which, as usual, in my view includes both politicians and business leaders) and reality on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/robertolofaro/posts/10156399476757016

Well, those who met me in Brussels and London or other European towns while I lived and worked there already heard similar comments from me.

Actually, also from other Italians living abroad, but still looking at Italian affairs and working in paths similar at my activities up to end 2007, interfacing at Cxx level.

Now, what changes is the names of those involved- but behavioral patterns? No, not really.

Italian economic development post-WWII

Over the week-end I read few books that I picked up in a local library as recent discussions in Italy reminded me of the difference between wannabe leaders and leaders.

The former talk a lot, issue "fatwa", and generally care about expanding and keeping happy their following.

The latter... lead by doing and having their following do more than they themselves assumed to be able to do.

Search for leader on this blog to read previous articles on this specific cultural issue.

The book links that you will find in my commentary below on each book are actually links to reviews that I posted over the week-end.

Now, the books I picked up were about the history of electoral systems since the unification of Italy in 1861 to 2018 (a disappointment but still useful pointers- about the roller-coaster of electoral law reforms), and two books about a person who played a special role in the late 1940s and up to the early 1960s within the "industrial history of Italy".

Why that range (1861 to 2018)? Because it matches the "range" that I read and studied in the past, albeit on the specific issue of elections and electoral systems, probably a book on the history of the Ministero dell'Interno I read few years ago was more informative (so, I will get back to those books, if still available).

All in Italian, I am afraid, but probably a short book (less than 100 pages) containing few speeches can highlight some key themes on Italian industrial development post-WWII.

Another book, focused more on the foreign affairs side of Enrico Mattei's activities to turn the request to dispose of a company focused on oil created by the Italian fascist government (1922-1943), AGIP, into creating a still existing and developing energy conglomerate covering also the production of related machinery, R&D, engineering services, etc- the ENI group (there have been changes across the years, notably after the post-Thatcher Italian variant of privatization, but it is still one of the major players within Italy, and one of the few with a projection abroad that extends beyond mere selling activities).

In Italy, routinely companies complain that the cost of energy is a competitive disadvantage of Italy, along with ineffectual bureaucracy, even more than salaries and corruption.

Part of the initial impacts of those 1950s-1960s activities within the energy sector was to enable access to fossil fuels at more favorable conditions than what would have been obtained by a country with almost no say in energy production.

Then as now, a country with scarce energy resources (if you ignore those potential but not used enough: hydroelectric, wind, solar, biogas, etc) had to take on debt in order to finance, also because historically in Italy the debt is mainly public, the assets are mainly private.

The trouble is: during the expansion of the 1950s and 1960s actually debt wasn't as substantial as it became from the 1980s-1990s.

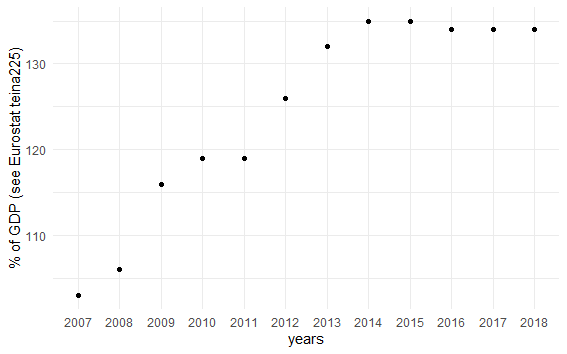

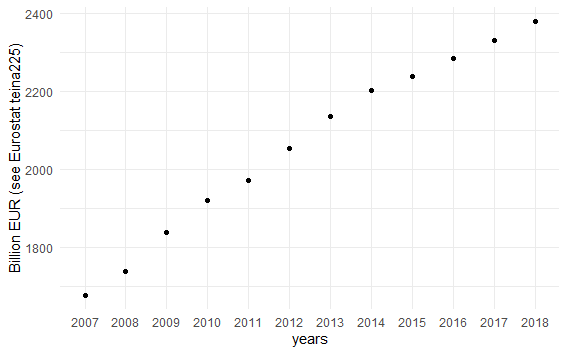

I looked for data in Italy, but then decided to use those provided by Eurostat, as we have a shared "harmonization drive" that makes data comparable.

Today, I will use only the data about Italy, focusing on data since 2007:

In Italy and in Brussels, way too many talk about "% on GDP"- yes, I know, it is due to Maastricht: but, frankly, it does not make sense.

If you contract the size of the economy, reducing the percentage implies cutting not just expenses, also eventually investments- which, in Italy, for reasons I wrote about before, often means "non-selective cutting", i.e. cutting, say, x% across, no matter what the (future) consequences.

In Italy, various rounds of privatization and externalization actually resulted, from my observations since 2012, in transferring to citizens various processes (and associated costs) that in the past were taken care of by companies owned by either the State or local authorities.

Once you privatize a company, markets control prices, and additional costs resulting from process transfer and increases in fees often are not considered "tax"- but if you are a person, family, or business, the impacts are not neutral.

Therefore, I think that it would be interesting to assess not just the taxation (which is already within the "top echelon" of European Union Member States), but also costs transferred.

As an example, considering the cost of kindergarten and the lowering of salaries, recent newspaper articles reported how parents sometimes see less expensive to have one of them to stay home if they have one or more children, than working and sending the kids to kindergarten.

Anyway, that would be a political minefield: which data should be considered? Which service model should be considered as more "sustainable"?

Whenever I discuss with fellow Italians about e.g. the Euro, or reforms in support to business, few are "non-selective" in presenting the data.

So, whenever I see a dialogue between those ignoring the data presented by the other side, I let them play their theatre: black-and-white discussions are not realistic, in my view it is always a matter of choices, not of "manifest destiny shown by data".

Incidentally: since I returned to Italy, I saw that again companies started adding a "corporate kindergarten" as a perk for employees.

A good initiative, but if not balanced by what few local authorities tried (covering the costs of kindergarten, an investment on the future), the risk is to increase the divide between those who have access to steadier jobs with a company that provides corporate welfare, and those working within the "gig economy" (in Italy, I met also people who have been working that way for the same company for a decade or more) with no support net.

Closing this digression, let's turn back to debt.

I rather look at the actual value than at the percentage of GDP.

In 2007, I remember discussing with my local (well, all foreigners) contacts in Brussels the Italian debt, at the time at slightly more than 1600bln EUR, stating that, if our "leaders" did not change their approach, maybe we will talk in few years, few hundred billions later.

Well, I think that I was, as usual, an optimist, as I remember talking about 400bln.

For today, I will share just the data and trend about Italy:

As you can see, while, after a spike few years ago, the % stayed more or less steady, the actual value kept growing.

I will not discuss the details now, what matter are trends.

Now, probably, you can understand why, beside some interested "spin" from those who were actually part of the Government that negotiated changes to the MES/ESM and suddenly discover it as if they had been sleeping during the negotiation, blending the words "debt" and "restructuring" in Italy is ruffling feathers.

Europe and Italy

As I discussed recently with a friend who asked me what I do think about the MES, I think that MES/ESM, as the Euro, is just an element within a larger picture.

Not too bad as an escape route: but as I said to my friend, I see no reason to read it now- it is basically final, we did not have that much negotiating power (see the debt volume above), and I will wait until the dust settles, as ratification and implementation are what matters.

The website of the MES/ESM outlines the key point: "The revised ESM Treaty will come into force once it has been ratified by all 19 ESM Member States. This involves approval in parliaments in all Member States. The ratification process will start following the signature of the agreement amending the ESM Treaty."

Somebody attacks the MES/ESM changesm, but really as a twisted way to resurrect their old idea of leaving the Euro.

I agree with most of what somebody better qualified than myself (and most of those writing about it), Luca Ricolfi, wrote in a short post.

Yes, Luca Ricolfi rhetoric is sometimes a little bit "extreme", but between the critics of the MES/ESM he is one of the most balanced.

To balance that off, a former minister, Pier Carlo Padoan instead stated why he sees how some changes were an improvement.

Frankly, both converge from different directions (Luca Ricolfi from an overview, Pier Carlo Padoan from "technical" details) on the same point: Italy made the best it could of a bad negotiating position.

Personally, I disagreed decades ago the Multilateral Agreement on Investment that tried to transfer political power to non-political appointees, and as I discussed with my friend I think that the MES/ESM, as well as other institutional changes, are still deriving from the upside-down approach to European integration.

As discovered by some small local authorities in UK after voting for Brexit, the European Union has an "harmonization" effect, e.g. by providing funding to reverse depopulation of small villages, islands, and mountain villages, as part of the European cultural heritage.

Many of those receiving funds in such a way have a tiny population- hence, in a democracy, they represent little or no interest for national politicians.

By leaving the EU, why should the European Union keep funding small villages in UK?

Still, having de facto no independent budget, the European Commission is severely constrained in doing what, in other countries, would be done by a federal government, to redistribute and balance differences.

The European integration developed mainly through a "jump forward whenever there is a crisis", as that was a way to circumvent the reluctance of Member States to do the obvious: surrender part of the sovereignty to reinforce a shared organization.

I am a federalist- but I would prefer something more "democratic", also if I think that the proposed European Constitution that, once torpedoed in France and the Netherlands, generated the "jump forward" of the Treaty of Lisbon, was a typical legal contract.

What would you expect from a constitution? Motivation.

If not on the level of "We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America", at least something closer...

What was the proposed European Constitution? Boring.

So, instead of creating a federal state with a federal budget, we keep tinkering with elements that, once introduced, to become workable arrangements, need... further tinkering.

The European integration framework was already getting lost into technicalities with the Maastricht Treaty.

The Treaty of Lisbon, again, wasn't a "motivational" document.

Do you read the "terms and conditions" of each contract with an utility or software license that you receive?

If you do, then those documents would be appealing to you.

Otherwise... not really that much (and I wonder how many of those who voted for or against in 2005 in France and The Netherlands actually read it).

Nonetheless, that "shock" re-launched a debate on the "democratic deficit" of the European Union institution.

Sharing the burden ahead

I do not subscribe to the concept of "eurocrats": it is akin to when, decades ago, an Italian President complained about "technicians from the Moon" who had designed a tax return.

If blending the demands and political petty projects of the Italian Parliament resulted in a tax return that I think was assessed as requiring more than a M.A. to be able to competently complete it, you can imagine what happens when (as in the MES/ESM and other Euro-related) 19 countries representing 340 million people get into the picture.

So, what matters is the concept.

Since the Treaty of Lisbon, a rebalancing of power de facto was attempted- expanding those of the European Parliament, contracting those of the Council of Ministers, building up an embrionic shared position on foreign affairs and defense, etc.

The Juncker European Commission that just ended its term was actually working on an arrangement where the President of the Commission was supposed to have political value, being chosen between candidates proposed by the European Parliament groups.

This arrangement was a step forward in reducing the "democratic deficit"- not anymore a backroom deal President (an arrangement that, instead, the governments of many Member States still favor).

Due to the results of the recent European Elections, this option was not available, so a new candidate was chosen and selected by agreement between the European Parliament groups.

So, at least formally, we followed the same line.

Now, there are already attacks at the budget: the President of the European Commission proposed a budget, the (rotating- in January will change) Finnish President of the Council of the EU asked for a cut, the President of the European Parliament stated that a cut will not be accepted.

Yes, the three Presidents are having a dialogue.

If you read the 18-month programme of the Council, you can see that the more we integrate currency-wise, the more necessary becomes "whatever it takes" to make it workable.

At the same time, we keep adding other integrations (energy, etc.)

So, in the limbo between what we have and what we would need to have, "technicalities" pile up.

Seen from the outside, looking forward, personally I think that we will end up enforcing the mutualization of debt.

Which implies also harmonizing the concept and structure of debt.

And, of course, implies also its oversight, to avoid that pooled resources are sucked by "free-loading countries".

As you can see from the "% GDP" chart above, Italy did gradually try to stabilize in those terms.

Albeit the issue is the stock of debt, and the side-effects of what was done to try to keep it under control.

If you e.g. postpone intervention on infrastructure, eventually that affects the ability to generate revenue.

A website called "debt clock" reports that Italy has to pay 3k EUR per second (!) just in interest.

Annual value? 95,589,326,744 EUR

An amount that is larger than many of the revenue redistribution elements within the current budget.

According to a document from the Bank of Italy of 2008, the debt was in December 2007 1.599bln EUR, and went over the 1000bln threshold in 1994, while was 1/10th of that in 1980 (converted into Euro).

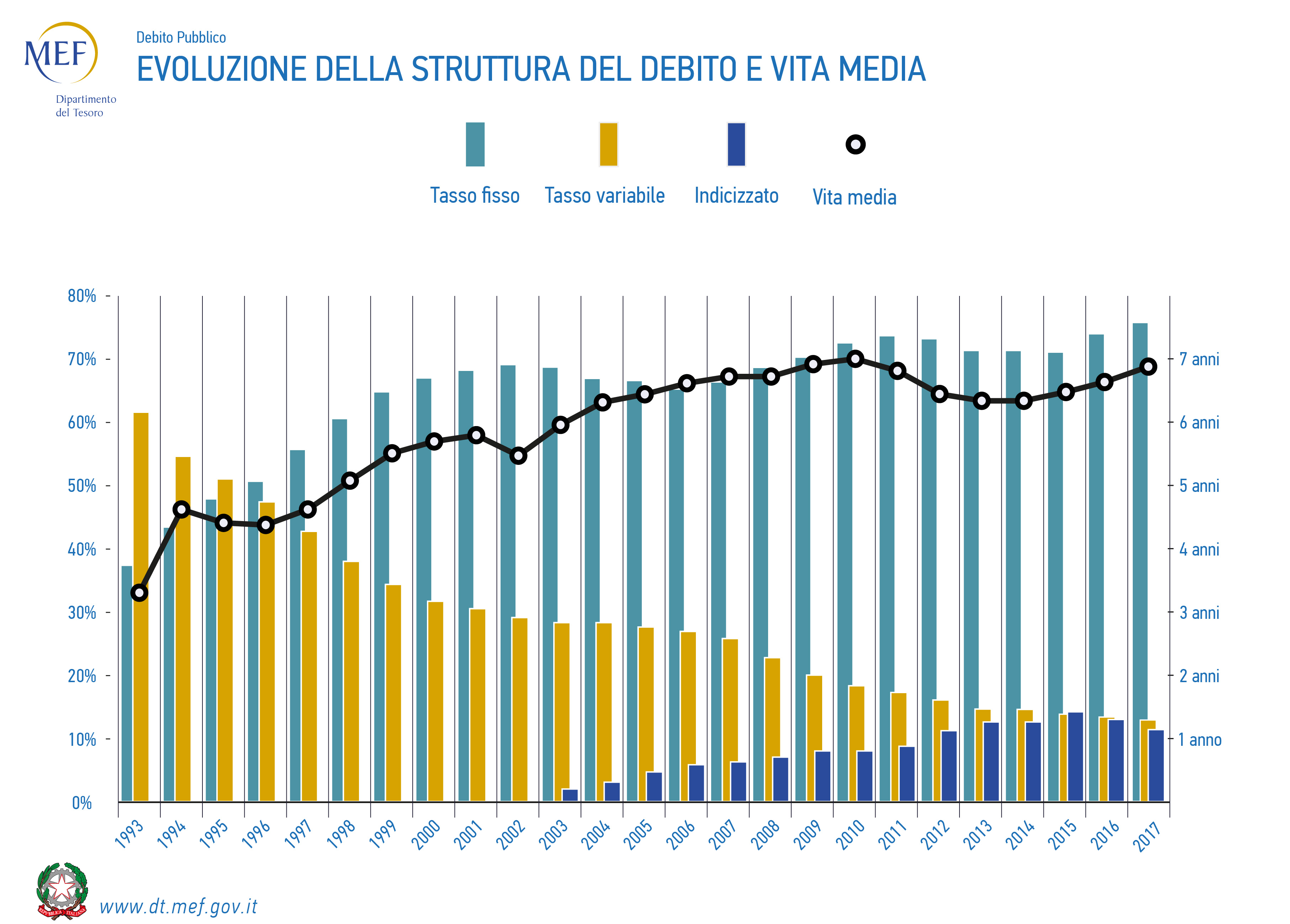

The good news is that the Italian debt since 1993 extended its life (chart from Italian Government; other data available):

So, what is the brouhaha about the MES/ESM coming from Italy? Too little, too late- and mainly to support a political style that reminds me of what I read about Byzantium.

I remembered in previous posts few times something I read in a Kissinger book, where he wrote that Italian Foreign Affairs Ministers (he was talking about over 40 years ago) did not seem that much interested in foreign affairs.

Unfortunately, a Pavlovian reflex of Italian politics: foreign affairs since decades have been considered as a tool toward national politics, and we are still applying to foreign affairs the negotiating style that is common in Italy.

Or: you negotiate, but if you cannot get your terms, you accept- then, during the implementation, each event turns into a re-negotiation.

As I said to my foreign contacts when I worked with them: almost nothing is ever final, so look at the practical side, not just at the theory.

Newspapers could add a service to readers: the cost of each statement affecting foreign affairs that is carelessly uttered by our politicians.

If it were a political choice, well, reactions would be factored in- you cannot make an omelette without breaking few eggs.

But in our case often the cycle is the following: statement, market reaction, statement reversing or altering the previous statement.

And this is not just a current issue, as by reading the Italian articles on MES/ESM you could assume: it is a routine that I observed also in the past, at least since the late 1980s.

Now, what will happen?

Your guess is as good as mine- but I am still inclined to see a forthcoming spring election (if those provoking it will see it to their own advantage).

Otherwise, we will resume a pattern toward... procrastination while fighting a continuous political guerrilla war.

_

_