Viewed 16615 times | words: 11352

Published on 2023-12-19 23:10:00 | words: 11352

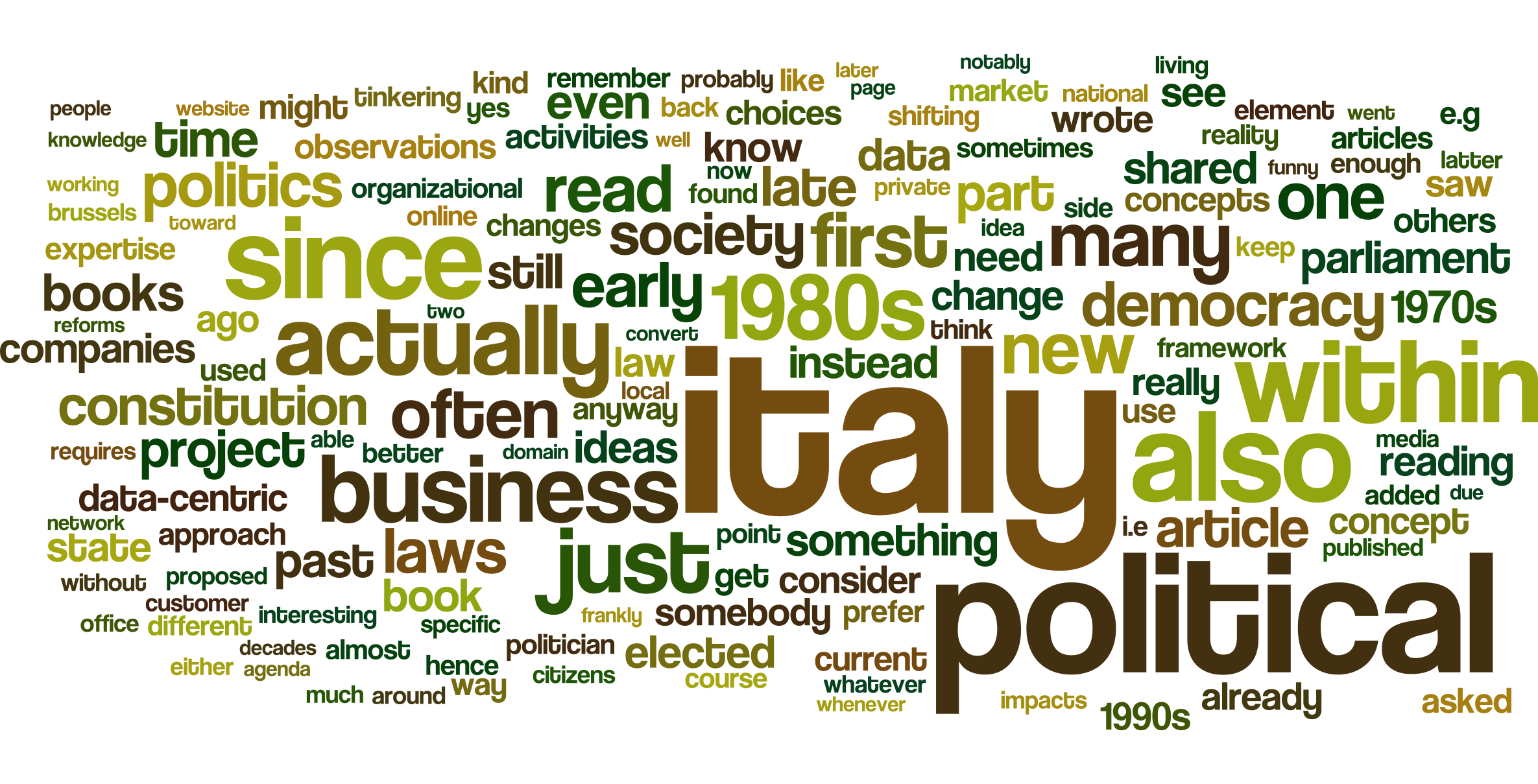

Few days ago, updated an article from the Data Democracy section, specifically about Law&Versioning in #Italy - an experiment in #swarm #democracy.

Somebody could ask: what has law-making to share with data democracy?

Moreover: with digital transformation impacts on society and business?

In my view- a lot.

Ditto for cultural and organizational change, as will explain later.

As I added in that article on 2023-12-05:

" moved this article within the "DataDemocracy" section, as increasingly anyway regulation and legislation, in Italy as well as within the EU, is almost following a cycle of draft_release - lobbying_for_change - amendments (which does not exclude that the initial draft is actually subject to pre-emptive more structured lobbying).

A further article will follow. "

And this is, of course, that further article.

The "concept" page of the data democracy section that linked above had this incipit:

" If data is everywhere and everyone is both a consumer and a producer, everyone will be able to contribute to continuous improvement of services, products, and, yes, societies built around data.

Pending the development of Artificial Intelligence smart enough to allow, say, to utter (just to name one): "Alexa, please let me know which data are stored by Amazon, and alert me if somebody outside those that I added to my 'guest data list' visits it", and then combine with, say, "Alexa, please check how do I benchmark in my neighborhood in terms of trash recycling and water consumption"...

...we are stuck with computers, software, data scientist, and the like.

Anyway, for knowledge that has to be published online due to a law or regulation, or that is already published in other formats, there is no reason whatsoever that makes compulsory to use "technical" (business included, not just computer professionals) to access the information. "

In this article, I would like to share few ideas, observations, concepts, starting from... the definition of the latter three within the scope of this article:

_ ideas, observations, concepts

_ the lifecycle of laws in Italy as I observed since the 1970s

_ direct democracy, extreme democracy, and realistic democracy

_ looking again at the Italian Constitution, but in evolutionary terms

There have been few changes since I first prepared the initial drafts that others already read, commented, reused, but actually it was the actual writing of the article and reading of the news that inspired a mild redirection.

Ideas, observations, concepts

The cycle within the title of this section is quite common not just in business, but also in society.

Someone has an idea.

Then blends with observations.

Then develops that into concepts.

The next step? Projects- which, as I keep repeating since decades, in my view extend way beyond a nice charter and plan- the real project is the execution, which might be somewhat different from the initial plan.

Actually, the observations often have to be both direct and indirect.

Hopefully from sources that you assume to be reliable due to past experience, not just due to the amount of "likes" or "buzz".

Reproducibility is a key element: if the "authority" of the sources implies accepting a "trust me" without supporting evidence, what is being asked to have is faith, not trust- and, probably, any observation provided by such "sources" is closer to their own ideas that any substantiated by facts.

It is a bit of the scientific method- as sometimes wonderful ideas do not survive even a tangent encounter with the reality of observations.

Now, the point is simply to subject your own ideas, or those that you are asked to contribute to, to a modicum of reality check.

It might be reality-reality (you misunderstood what was feasible).

Or it could also be political reality- both in business and society, i.e. acceptable-reality or even actionable-reality.

Example: say that you made a five-year plan that includes withdrawing from some markets, or, in politics and society, relocating a hospital after seeing that would not be feasible to renovate it.

The latter is a case that was discussed at length within a course on complex projects management / program management from Universidad de los Andes that "attended" (i.e. virtually attended on Coursera) in 2022.

If, like me, your projects and program activities have mainly been within the private sector (except, in my case, pre-business in the 1980s and some projects in mid-2000s), and mainly within IT or cultural/organizational change or finance or logistics, it is a worthy exercise to attend that string of courses to see cases as diverse as coping with a disaster involving recovering alive miners (I would call it "emerging project": unwanted but not completely unexpected- was a risk you had to have contingency plans for), adding new services to a community or, as above, relocating a hospital within a community that is growing but where there is an increasing gap between "have" and "have not" in terms of services and inclusion.

Why a "worthy exercise"? To extend the boundaries of your ignorance- what a USA politician famously called "the known unknowns", reducing a bit the "unknown unknowns".

Meaning: just because you attend a course, you do not turn an unknown into a known, notably when being able to act on that bit of knowledge required additional knowledge: I might be interested since forever about buildings, architectures, and the design of cities- but while I might, as I did in the early 1990s with a girlfriend who was townplanner, comment in reasonable way about the blueprint of a proposed construction and its surrounding areas, that does not mean that I would know all the regulations or have the skills needed to building something like that.

Which is something that often had in the past to remind to others: being able to understand the context does not necessarily imply being able to intervene.

In those cases, as discussed few days ago within a post on Facebook (and its version for Italian audiences) and a post on Linkedin, focusing just on the now and here is not enough.

Unless your "cone of visibility" is just the next electoral cycle, or your aim is simply to spend down to the last penny any funding available, by doing everything that is formally feasible- no matter how reasonable or sustainable.

If your aim is to leave a better place than the one you found (which, whatever "better" meant to you, used to be the purpose of politics), usually you have to balance between at least a couple elements in decision-making:

_ continuity of the present as a recognition of value of the past

_ "seeding" the future, by setting signposts that others will develop on.

Then, I would add a third one: it is not politically correct, but let's be frank- any decision-maker looks also at her/his own "value extracted".

This is worth a digression, as notably in Italy I heard so often the rhetoric of "selfless leader", that I got really bored, and more than once was first told that I was too negative, then asked where did I got the information to do that forecast.

Usually, along with suggestion that those who criticized me at the beginning for being negative, actually had already understood the same, but said nothing: Italy is the country of 20/20 hindsight presented after the fact as 20/20 insight.

When it comes to "profiling" people, often end up being as Al Pacino said within "The Recruit", "a scary judge of talent" (and no- I do not share his rationale within that movie).

Nothing magic there: you just have to listen before you talk, and try to understand what motivates others, not project onto others was motivates you.

Then, apply some "signal intelligence" to digital media publications (and some "Kremlinologist" skills).

E.g. a partner decades ago involved me each time he considered new partners for his company, and for each one of those I advised not to take onboard... eventually he asked me years later help to remove them from the company.

And it worked also the other way around: since at least a couple of decades, whenever I met somebody that I was told beforehand by gossipers to avoid or about supposed weaknesses, I simply ignored the gossip, and made up my mind.

For those that I considered positively, long after I stopped working with them, saw that actually they did get the promotions that they deserved- usually after leaving the gossipland.

Obviously, if they are within a team that you coordinate, then it is up to you also to help their talent develop.

My (applied) concept of leadership is relatively simple: if you are a leader, you have to help grow the capabilities of those around you, not just go around and collect prizes for yourself.

Of course, this requires also a mandate from the organization to actually do that.

The alternative? In Italy, since the 1970s I saw way too many supposed leaders who basically did not build capabilities, just developed their own "cornerstone" role or even had a mandate to do so: remove the cornerstone, and the whole structure collapses.

Actually, one of the most read articles on this website is "Il paese dei leader, published in 2017 and so far read by over 14,000 people.

The motivation of the leader could be financial, power, "becoming history" and projection of image.

Whatever it is, better to consider this third factor, the motivation of the leader, instead of pretending to ignore it, and then see how many "strategic decisions" are unbalanced by this third, ignored element.

Yes, there could be occasionally the selfless CEO or politician who comes, does, leaves, and is just happy about that- a self-actualization choice, usually supported by a form of parachute (could be another role, financial, or something else).

Anyway, since 2012 in Italy, and even since the 1990s while going around Italy, I had plenty of opportunities to look at self-declared "selfless" leaders who then ended up in one or another trap for their ego.

It could be something as innocent as shifting bottles in front of you while you are a panelist, to give cameras and TVs an clear line of sight to focus on your face.

Or lavish perks, as some of the recent scandals about "new ageish" companies within the new world of digital finance and real estate management in the USA.

In the end, also those most innocuous often enter a self-reassurance cycle where whatever they do is positive, hence they should become the default choice in their chosen domain.

Or: the longer they go, the less able are to collect "signals" from the environment that would otherwise have inspired adjustments.

I do not like a market economy, but this is what we have, so since the 1980s I said that we should make it work properly.

Hence, I dislike monopolists or those assuming that have a manifest destiny to lead a market or domain, and filter out all those who do not acknowledge their gatekeeper value.

Also because, as I wrote in countless articles on this website, in a data-centric society (which, like or not, is the one we live in now), eventually the most logic path is accepting that each member, individually or an aggregate, can make new lines of development "emerge": a data-centric society is also, by consequence, an experiments-based society.

In my view, we should add to schools "experimentation" skills, as our current use of social media is "success-oriented", while experimenting implies accepting failure as an option within any new initative, and learning from it: "fail fast, fail early" does not apply just to startups.

Anyway, these last few paragraphs would require probably a book.

End of digression, and back to the idea of concepts.

So, if you considered not just the idea and the observations, but also "framed" both within the context of "who" and their associated "why(s)", then defining the concept is barely a first step.

Defining a concept, in both business and advocacy activities, is not to "preach to the converted", but to see how much that concept is functional to advancing your own agenda.

It could be a convergence of interests, or your own "evangelization initiative".

Incidentally: whenever I found a startup that wanted to "convert the market" to their own offer, as nobody else was already offering it anywhere on Earth, I looked at how much they had moved along the line from idea to observation to concept.

In some cases, some of them were able to generate "buzz", and attract funding from those that they converted- but jumping directly from idea to concept while staying as far as they could from observations, as if a reality check was an issue.

Many of them actually paved the way to make a new market "emerge", with a potential demand significant enough...

...to convert existing companies with larger war chests to enter those markets, and crush them out of the market that they had helped to put on the map, but with some bravado assumed that they were the one and only able to develop.

Actually, I was in the past paid to be a kind of "Devil's Advocate" by customers and partners, to avoid getting down such a blind alley, and did it for free as part of the vetting of startups.

So, having a concept then requires a coalition of the willing.

Meaning: either you can get that mythical MVP (minimum viable product) on the market (and this applies also to political concepts), so that it is identified with you and any "copycat" is clearly seen as a copycat; or, if your idea-observations-concept show that you need some deep pockets, you might consider partnering, more than with financial VCs, with corporate VCs or similar "vehicles".

What I am referring to is companies built to scout for opportunities and associated teams, companies that are actually derived from corporations that understood that "making an elephant dance" is a nice concept- but if you get a startup inside a corporation, it is akin to "making an elephant dance with an ant"- and then burying it under piles of corporate vetting processes and forms to fill.

Now you would say: but why all this "business-oriented" discussion within the scope of an article on law making?

Well, unless you were on another planet, since at least after WWII (but also with the nepher of Freud in the 1920s, "Propaganda" by Bernays), also politics and political ideas have been a product for more than a century.

Actually, as I like to remember many of my more idealistic friends at least since the 1980s, corporations were actually invented to blend a projection of politics, not as a separate entity.

Anyway, look also at the Triumvirate in Ancient Rome: Caesar without the deep pockets and other elements from the other two "initial partners" would not have had the development he had.

Before talking about political science, I think that many would just benefit by reading about political history: we complain about "fake news" in campaigns, but, as I shared in the past, both in Greece and Rome politics was not that "fair game" that we think it to be.

To summarize: once you have concepts, converting them into projects (or laws) requires bartering with reality, what in business is called "scoping".

The lifecycle of laws in Italy as I observed since the 1970s

As I wrote above, this article has been in various stages of drafting for a couple of weeks.

The reason? I was observing the political debate in Italy.

In Italy, while since the 1990s we had a routine of "parachutes" landing into politics from civil society, before that we had political schools associated with political parties, or their on-the-job training equivalent, e.g. as an assistant.

The net result has been routinely shown by the "structural cohesion" and quality of laws and decrees issued by governments of different hues and shapes: declining, declining, declining- and requiring increasing amounts of ex-post tinkering.

Also, I remember how actually in both political activities in the early 1980s, and then in the Army in mid-1980s, before starting working in mid-1980s, helped something that I went through between the late 1970s and early 1980s, as part of my interest in cultures.

At the time, in school we had something called "educazione civica"- which sounds in English a bit a kind of Soviet-Orwellesque concept, which I could convert into "creating citizens".

In high school, in the late 1970s to early 1980s, we had in Italy a bit of a "partecipative" model, and for various reasons I ended up studying in libraries on the Italian "Gazzetta Ufficiale" (the official bulletin) a couple of laws that then explained to my classmates, and that, along with an historical research on my family and ancestors in Parliament, ended turning into reading not just the Italian Constitution resulting from the post-WWII "Costituente" assembly elected to write the Constitution, but also reading other Constitutions, and comparing them.

Maybe not the standard reading material for an early teenager- but was lucky enough that, if at 9-10 had moustaches and could ask for books at the ordinary (i.e. grown-ups) library (to read on site, as obviously when asked to register to take loans was redirected to the children's library), at 14 had a beard and therefore could attend the Biblioteca Nazionale Universitaria, to read books that, until archive.org and gutenberg.org, were not available elsewhere (e.g. I remember reading books from the early XVI century, that now you can find scanned on archive.org).

Reading about cultures and archeology since few years before, and how towns and bureaucracies had developed, while being in a "political" environment (saw live my first political campaigns in the early 1970s), implied that I was specifically attracted more by the "why" each Constitution had been designed, than from the usual long list of rhetorical promises of a paradise on Earth.

The "narrative" is always interesting- sometimes frankly more than parts of the results.

So, while preparing this article, and reading current news from Italy on proposed laws, reforms, and law changes following the first release of new government decrees and proposed laws, decided to read again a bit about the introductory/"framing" part of Constitutions.

My 1970s book about comparing different Constitutions is deep into boxes- hence, went to visit the Turin central library and picked up some more recent books.

A 2021 book on "Struttura e funzioni dei preamboli costituzionali - Studio di diritto comparato" was an interesting week-end read.

Actually, at slightly more than 170 pages, an afternoon read and study.

It complemented another, older book on "The Art of Storytelling" from 1963, that I am reading and cross-referencing with other more recent books.

Personally, the "ghost preamble" in many laws in Italy was the context and discussion before they added to the books, i.e. you knew about the debate (in some cases, actually books were published about the birth of specific laws), but the end result was "streamlined" to something that generated enough consensus- something that was often ambiguous enough to allow everything to find something into it.

Decades ago, I said to foreign colleagues that in Italy we are compulsive law-makers: at the time, we had 120,000+ laws, and eventually went up to a point where even a court had to admit that nobody could avoid ignorance of the law.

Another point that I said to my colleagues was that, generally, in Italy laws used to be ignored for the first few years- as the expectation was that they would be amended or withdrawn.

So, for example, we had already in the 1970s some relatively strict law on smoking in public places- I remember movie theatres where I had to watch a movie through a fog of smelly smoke.

When did, decades later, finally get applied universally? After yet another revisions added fines not just for the smokers, but also public place where they were allowed to smoke in violation of the law.

It happened almost two decades ago- and it was funny to see how, from one day to the other, in Rome suddenly bouncers in pubs etc asked customers to either go out or extinguish their cigarettes.

Anyway, until the late 1980s we had political parties that had a structural presence across Italy since decades, and therefore acted also as compensation chambers for interests- I really saw a change with what we call "Seconda Repubblica", from the 1990s.

First few changes due to a new political entity that was across the spectrum: nominally going as far as proposing a split of Italy in three states, but containing people that ranged from Castro followers down to somebody who set up "green shirts" (that to many remembered the "brown shirts").

As happened other times, obviously they too assumed to have the moral right to decide for everybody, and were, as any Zealot, quite intolerant.

Then, of course, the trappings of structural politics in Italy produced their magic, notably the Italian "spoils system", that does not bring just few managers focused on giving guidelines aligned with the new incumbents, but embeds vertically within the organizational structure of the State, after each win.

The net result of this approach? Confusing concepts (call them "qualified ideas") with projects (call them "ideas implemented").

When you start from concepts and try to convert them into actionable items, you need to consider also the resulting lifecycle and impacts, and this could further alter what was an actionable item, before it becomes an actual implementation.

This applies not just in politics- also in business, with a key difference.

In business, notably in a country where, as in Italy, many small and medium companies are private, while larger companies are either foreign-owned multinationals or formerly State- or local authorities-owned companies with a kind of hybrid status between private and public (e.g. on the stock market, but with top managers appointed de facto by elected politicians), only smaller entities are really answerable to business dynamics (market, owners), and can alter decisions to the point of immediately contradicting themselves, if that makes sense.

For larger companies (multinational or local "hybrids"), decision-making is somewhat more complex, as other elements have to be factored in.

No, I am not ignoring corporate politics in larger companies: even when abroad, saw decisions influenced not just by business needs, but also by business face saving.

In politics, notably in Italy, we moved from an era when routinely we had newspaper report discussions from politicians that were denied the following day by the same politicians, with journalists eventually reporting that they had started taping interviews, just in case.

The point was: spreading a message and then denying it- after it had reached the intended audience: the Italian political version of "plausible deniability".

Then, courtesy of the proliferation of private radio and TV stations between the late 1970s and early 1980s, we shifted to an "open mike for everyone".

And eventually to having, in the Internet era, two main collections of channels (State and Berlusconi), few middle-size players, and various radio, TV, Internet, etc venues for all to use.

This changed the political discourse, as on a daily basis you could hear and read (and, from mid-2000s, increasingly see online) politicians almost permanently giving a speech or chatting with journalists in one of countless formal and informal talk shows.

And if you missed a talk show- do not worry, that same night or the day after the key segments from the broadcast appeared e.g. on YouTube.

In the smartphone and social media era we had a further evolution- which, for Italian politics, started later than elsewhere- see a book (in Italian) that I shared over a decade ago, after seeing, while living in Brussels, how still backward was Italian politics in the use of new media.

What changed? Bypassing traditional media, beside the expected online meetings and "consensus-aggregation" theads on social media, Italy, as done in other countries, gradually developed again the "meet in the square" politics that I was part of as a teenager between the late 1970s and early 1980s, with a twist.

Back then, those attending marches or even one-off demonstrations did so mainly as part of a "structured" political choice, guided by political parties with an agenda or other organizations (from e.g. part of the Catholic Church), or consensus on a specific theme of the day (peace, a law, etc).

The recent return of the squares as political aggregation venues was more for pretended "grassroot" political development.

Pretended, as often turned into top-down hierarchies with even less internal democracy than had past political parties.

Since I had to return to work in Italy in 2012, shared routinely on Facebook (where I post most of the social and political commentary on news) and Linkedin (where I post most of my business and science/technology commentary) relevant posts.

Political events turned from being part of an agenda dictated by others, to being a kind of (pretended) collective agenda-setting.

In past political aggregation events in the 1980s, there was anyway a continuity between "meet in the square" or "march", while in the 1990 and more frequently in the 2010s saw a series of "rituals".

As I was based in Turin few years ago for a project, I saw that it seemed as if each day during the week had its own "scheduled sit-in"- week after week.

The interesting part is that in the past we had the routine of "we do this because Europe asks us", whenever reforms or laws with scarce local support where added (reforms and laws that, often, were what the Italian Government of the time actually proposed).

The old model implied a kind of long-term learning path, while the new one seems to be able to extend to political leadership what we had in Italy in former State companies and larger companies since well before the Italian Republic was founded, past WWII, the "parachuting leadership" (i.e. somebody appearing out of nowhere to a leadership role).

If you remove the learning path, often you remove the possibility of developing that shift from ideas to concepts by integrating with observations, and your "projects" lack depth.

When I returned to work in Italy in 2012, but even before, while I was reading and commenting online from 2008 while living in Brussels, I saw how the "Second Republic" since the 1990s gradually expanded the lack of depth, coupled with willingness to accelerate the release of laws and reforms.

The solution? Create laws and regulations that were "skeletons", and let bureaucracies fill the blanks- sometimes actually generating something that was not intended by the official vote in Parliament.

Since a decade ago we had a further development, the one that I observed on a weekly basis in Turin while working there, which often brings back to mind "Our Man in Havana" or its version by Le Carré "The Tailor of Panama".

Or: a few turned into a "silent majority" that justified pushing this or that point on the national agenda, bypassing all the constraints of representative democracy.

Also, there is little political praxis continuity outside those "get together" (offline and online) moments.

And, of course, as happened also centuries ago, once that agenda is set, and representatives of that agenda are elected, suddenly... again the trappings that absorbed others in the 1980s and 1990s absorbed also more recent ones.

I am not saying that it is a decline- it is a different model for different times, coming with different models of participation, often extending of the pre-existing "tribal" culture of Italy, shifted also to consumption models and purchasing choices.

Yes, sometimes, when I see all dressing in the same ways, or buying the same computers and accessories, and sharing the same Zealotry while talking, as a kind of "virtual tribal tattoo", I think about the Nika riots of Byzanthium and its "blue" and "green" sides.

Conformism is a structural element of tribal groupthinking, to the point that being innovative is associated with the purchase of specific brands- I remember how funny was the short time when "no logo" became trendy, so that you could see many "no logo" branded items, supposedly as signs of individuality and against... branded clothing and its associated logos.

It is almost entertaining to see some politicians state that the Parliament is where political ideas are discussed- after instead having been suddenly pushed to national fame by the new model of participative politics that appears "collective", but it is really even more "dirigiste" that 1970s or 1970s politics.

If you read some of my previous articles, you know that I consider our current trend in Italy a kind of "mob rule", highly exposed to potential manipulations:

_ you need to craft an appealing message

_ that message generates/attracts support

_ you corral that support to increase it "punch value"

_ you "spend" it before it vaporizes

_ you end up convering your agenda into "being there"

_ you care about the consequences and motivation later.

If you get into this "tinkering cycle", the risk is that you actually remove any possibility of political discourse, as each interaction is expected to generate immediate effect- not really what is needed for a complex society where every interaction potentially could alter action.

Direct democracy, extreme democracy, and realistic democracy

Yes, I have been working since the late 1980s doing "iterative" and "incremental" activities, and I advocate, in a data-centric society, more understanding of experimentation and its consequences.

I remember already decades ago the State national agency tasked with managing retiring benefits and other elements of welfare in Italy asking Parliament to reduce the continuous "tinkering" that had grown to almost a monthly basis, as each time they had to reassess the impact on millions of positions- and having what was said to be back then the largest data centre in Europe was not enough.

Reactive politics, or politics based on "sentiment analysis" is what both parts of the centre-right and apparently most of the centre-left seem to be focused on nowadays in Italy, generating a kind of consensus on the method that supposedly works with law-making in Italy, 2020s-style.

Anyway, as I often had to say in Italy since 2012, the State is not a mom-and-pop grocery store, where you can switch direction at will.

When it comes to the State, where a single ministry might have tens of thousands of employees, and a single change might affect the life and choices of millions, if you do changes, you need to have a depth of observation and analysis that often in the current need to keep visibility and apparently be the "leader of the direction" does not allow (yes, our Italian obsession that described in "Il Paese dei Leader", that published in 2017).

Which is the same reason why I shared above the concept of large companies shifting from "making elephants dance with ants" to "supporting ants at arm's length", but flipped the other way around- it is up to the elected ants to understand that the State (and the impacts of any of its actions) is an elephant, with its own rituals, degrees of complexity, etc.

As I shared in past articles, it is quite curious how the increased superficiality was coupled with a popular demand to have "competent politicians", "competent leaders".

Let's say that you are highly expert in A, and therefore used to have confidence in your assertions about A.

Once you get elected, one day you will have to vote about A, then about B, then about A+B, etc.

And, while your own choices within A while you were a private citizen were going to have a limited impact, if you get the power to cast your vote to add a new law, you have to consider the impacts outside your own cone of visibility.

So, frankly, as I wrote in the past and above, whenever I was told "we need more competent (leaders, politicians)" I asked: competent about what?

Actually, as I saw in cultural and organizational change and business number crunching since the 1980s, having competence in a specific domain is useful to have a forma mentis that hopefully is used to consider systemic impacts and "boundaries of ignorance" of your own knowledge (the "known unknowns").

Unfortunately, often the latter characteristic is dropped and replaced by a need to confirm the status.

Therefore, having experts in whatever in Parliament might be useful, but if they consider that any expertise that they have, while in office, has to play second fiddle to systemic (and procedural) needs, and if they also accept the concept that saying "I do not know", followed by "who are our experts on", is fine.

Anyway, Italian citizens too need to grow up and understand what means being elected- which is not a way to "settle" your whole family and clientes.

Elective office is not limited to the time you spend in Parliament or office, also if many Italians seems to consider fine to compare a 9-to-5 job with holding an elective office.

An elective office is akin to a Cxx office in business: often, have a potentially 24/7, and also when not within Parliament or whatever office you have been elected to, you meet people or think reconsider plan organize.

As I shared in the past, I was introduced to the community of "extreme democracy" in mid-2000s, in Milan, by a Japanese who introduced me also to "creative commons", while attending a post-event night in Milan at the IBTS (a broadcasting event).

I was there along with the founder of a startup that I had supported by developing the business and marketing plan that won a prize (no, I did not make a penny out of that- it never started, long story).

Actually, some of the material on the then website of the extreme democracy community echoed material I had read online since the 1990s in mailing list SIGs (special interest groups) within Mensa USA.

Or: discussions about how to organize society from those who had a mechanistic view of politics, as if the "third element" I described above while discussing about leaders did not exist, and mainly from those coming from outside political science or even organizational development.

Yes, I am currently working on data-centric projects (to then embed within my publications) and products (to see if I can generate revenue streams), and discussing our data-centric society.

Anway, luckily my interest in computers actually started after I had developed an interest first in cultures and archeology, then adding how the human brain worked, and at the same time when I was spending time in libraries reading the "Gazzetta Ufficiale" for those lessons I described above.

Hence, I am quite skeptical of each and any "reformer" who proposes changes that might work in pipelines or machinery with preset degrees of freedom and known structural weaknesses, but not with people who can, notably in groups, evolve positively or negatively.

Yes, I am skeptical of the "wisdom of the crowd": as somebody said, given infinite time, a team of monkeys might write all the works of Shakespeare- and others added that, according to Darwin, actually one evolved monkey already did.

Still, I think that if you put in a room a group of people sharing just their ignorance of what they have to decide on, the results cannot be positive: they should have support, at least procedural support.

Otherwise, those who shout more or who are better at manipulating consensus will carry the day.

Manipulating, not building: as within the context, the point is converging votes, not converting voters (i.e. those who have been elected in Parliament).

Hence, I think that those elected should focus on contributing their expertise, and then having it play second fiddle to the "rules of the game" of the body they are elected to, as well as the "why" they wanted to get elected (hopefully, as I wrote above, because they had an idea of how to leave behind a better future than the one they found).

As I write often, 99.9% of what is on my CV does not derive just from the schools I attended, but by learning.

Learning from books, courses, from doing- but, most importantly, by listening to those who knew better, and having no fear to ask "stupid questions", and saying "I do not know" when I did not know.

Recently I found quite funny to see an encore of what I saw in Brussels, when some recruiters tried to convince me to "tweak" my CV by converting "having coordinated" or "project managed" something into "having expertise in something".

I worked with many of those "having expertise in something", be it managerial or "technical"- and I respect them enough not to claim to be a peer of what they are unless my knowledge is current, relevant, and kept in use.

Also those elected who try to pretend to be experts in everything are more than worrying, in my view, as they project the wrong expectations and eventually risk to believe their own pretensions, often shutting out anybody who does not support them.

Learning is fine- so, also those who got elected without having read not even once the Italian Constitution can still find those who know better, and learn, but requires humbly accepting that to contribute you need to join the discourse, as the system has to survive your passage.

In Italy, we shifted from backroom dealings between different "tribes" within the single majority party (as we had until the Christian Democrats had almost a permanent relative majority, i.e. until late 1970s and even later), to having a "test run" of different coalitions in government after each election since the early 1990s, with a significant frenzy since the 2013 national elections.

In 2013 a new political entity, Cinquestelle, obtained a significant success, becoming the first political party, with 25.5% in the lower chamber, and becoming again the first political party in the following national elections in 2018, with 32.7%.

Their initial proposal was to have a kind of direct democracy, where each elected representative was just a "voice" for the voters.

The first issue was: while having a fraction of members vs. voters, members were those who were proposed to "express the will of the voters"- calling "direct democracy" having around 100k making continuous choices for millions who never voted for them, just on the basis of a card-carrying membership is not my idea of direct democracy, or even representative democracy.

Moreover, the wording and choices proposed were decided not by voters, or even the members, but from "umpires": anybody who answered a political poll knows how this could affect results.

Finally, this would actually remove completely the deliberative process that, in a representative democracy based on a Parliament, requires elected Members of Parliament to actually discuss and build a consensus which might evolve, not having just a yes/no on each option.

The second was: in Italy, each Member of Parliament, according to the Italian Constitution, is not constrained by party discipline, to avoid having the rubber-stamping, single-party Parliament that we had during Mussolini times.

Hence, considering that those elected were supposed to stay no more than two terms, it did not take long to see many of the "behavioral promises" presented to voters to be dropped.

And, as it happened to the Northern League between the 1980s and 1990s, gradually, but faster, Cinquestelle became a "normal" political party.

So, the Italian experiment in direct democracy faded quickly away.

Instead of direct democracy that anyway requires campaign, dialogue, and time to "convert" to a position or its alternatives, we shifted since 2013 increasingly toward a "sentiment analysis democracy".

The key difference? The former is a diffused legislative process that takes its time, the latter requires being continuously reactive to the latest fad, and, as discussed above, is easier to manipulate.

You need just to generate "peak visibility" in a short amount of time to generate a series of "reactive choices" that often have no time to be subjected to proper analysis about their "systemic impacts".

I would prefer shifting toward a "realistic democracy", the third element of the title of this section.

Which is simply based on decoupling principles that you stand for from what instead could evolve.

So, I agree with what a priest whose political school attended in Turin and recent commentary: the first part of the Italian Constitution should be left untouched, as it is de facto the "framework" of what follows.

Which, incidentally, was how I worked since 1990 whenever asked to improve processes or organizational structures: "frame" your purposes and guidelines, then the rest will follow within that framework.

In business, this is called "context"- and I saw the net results when, instead, somebody introduces organizational changes ignoring the "cultural framework", often as copycat with adaptations from what already done elsewhere.

In cultural and organizational change, already in the 1990s was told by customer that they recognized when there was a "scale up" approach in place.

Simply, they met during negotiations those with advanced listening and rephrasing skills (usually a partner), then the project was assigned to somebody who had prior experience on projects within the same industry (usually a manager), who started with somebody that was a pre-cooked framework, and then proposed to send around teams of consultants to interview, collect information, and (more than once), actually converge business users toward what they had to offer, meanwhile generating massive amounts of billable hours.

As a consultant working both on the customer and vendor sides, sometimes I was actually asked to "temper" this "expansion drive".

Looking again at the Italian Constitution, but in evolutionary terms

I think that my business activities since the 1980s, as I write in my motto on Linkedin "with and without technology", did actually benefit from the systemic view developed as a teenager studying cultures and reading law and Constitutions when I had time to think, toy with ideas, and discuss them with others with different views: something that in business often is not possible.

I know that the locals in Turin still comment sometimes that I am too technical (when they are not) and sometimes that I am not technical enough (when they are), but, frankly, it is a matter of roles, purposes, perspectives.

I think that in any organization complex enough there is a need of a mix of profiles, not just in Parliament.

To stay on something that could be more understandable to both technical and non-technical audiences, let's discuss from the point of what is needed to make a modern company work: computers.

With current advances of affordability of technology, including the potential instantaneous scalability offered by cloud computing offers such as those of Amazon, Microsoft, Google, etc, also small companies can convert into OPEX (operational expenses) linked to revenue what in the 1980s was pre-emptive CAPEX (i.e. investments before even starting operations).

Example: in the 1980s, I remember a customer complaining that they had purchased and installed mainframe resources that were to cover for 12 months- but the way a system was designed actually consumed much more than expected.

In the 1990s, a customer said that they had designed their own local area network to sustain those "black and white" screens, and shifting to the early Windows-based generated too much traffic and, to obtain the same service, they needed to redo the network design.

In the late 1990s, a customer wanted to use a nice graphical interface around the offices in its country- but in Europe the cost of a really slow network (it was early Internet, T1 was generally available only in the USA) was greater than the cost of a T1 allowing that in the USA.

Shift to the late 2010s to early 2020s, and you can see how broadband networks and cloud computing allow potentially a tiny startup to invest next to nothing in hardware and network, and use a pay-as-you-go which, if coupled with a pre-paid subscription model, enables to grow without much capital.

If, instead, they go on the pay-as-you-go use of network and cloud computing facilities, forgetting to link that to the cashflow generated by customers...

...there is a list of movies and documentaries and books showing how many startups went belly up by focusing just on technology and service, and forgetting sustainability.

Now some would say that I am shifting toward too technical a side: but, again, this website is about change with and without technology.

I wrote in previous articles that I actually follow the line of those who over a century ago wrote that corporations have political impacts, de facto turning into political actors- also if you ignore lobbying and corporate funding of political campaigns.

Technological and business choices have a political impact- and political choices have business impacts: ignore either side, and you have to attach yourself to somebody else's choices, as it happens to many small companies in Italy that have been unable to "scale up".

After the 1990s OECD initiative on e-government, it is ordinary now to consider technological delivery of services a way to both lower the cost of delivery of services from the State to citizens, but also to increase inclusiveness- and pervasiveness of services, accessible anywhere anytime by anyone at marginal or no cost.

So, business choices about the availability and affordability of services such as Internet access are actually the potential to impact on political choices on the relationship between State and citizens within a data-centric society.

In Italy, we had a prime example in the late 1970s to early 1980s, when it was thanks to political choices that private TVs and radios were allowed to expand and stay on the air, developing what was to become the first private TV and media network able to really compete with State TV.

I know that my Italian contacts almost to a whole utter that it was Berlusconi who introduced in Italy the concept of selling politics as you sell soap- and technically this might be correct.

But, frankly, already the 1940s elections of the new Italian Republic including plenty of marketing via advertisement that reminded WWI advertisement against enemies (and while in London found some curious 1910s books about the "German danger" in the USA).

We live in the XXI century: hence, and this is the theme of this article, we have to evolve to an environment that is data-intensive and data-centric, while most of the processes we use in decision-making as based not on continuous data, but on discrete data.

Currently, we are still used to "fix reality" at the beginning of the decision-making cycle, and then assume that whatever regulation and law we issue is a side-effect of that "framing".

Instead, as I saw first in political activities (number crunching from Brussels and Strasbourg early 1980s), and then in business (business number crunching in the late 1980s), the "reality" you based your decision on evolves, and might require more flexibility.

The Italian Constitution has been modified frequently since the beginning of the XXI century.

It is a paradox: lack of cohesion and "idealistic traction" in political organizations resulted in constant tinkering to try to build a stability via the regulatory framework, with the obvious result that each electoral round, following the Italian "tribal" approach, resulted in further tinkering.

Many times such tinkering is described as a need linked to crises- but emergency-driven tinkering often resulted in "temporary fixes" that then became permanent, and a source of further tinkering, until became a Gordian knot that had to be cut, with a bipartisan consensus to restart afresh.

Whenever I hear "emergency" uttered along with a new law proposal, as shared few times in the past this reminds me of an old movie, "The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming", about a vessel getting beached, being mistaken for a landing beachhead for an USSR invasion of USA, and turning into a collective effort to save the day.

I am boring, I know- but as I wrote above I would prefer to keep the first part of the Italian Constitution "steady", and have a new elected "Costituente" with a single purpose: restructure and redesign the Italian Constitution following the spirit of the first part, plus a renewed consensus of an Italian Republic within a multinational context and as a step toward a further integration within the European Union.

Because while the first part is a kind of "preamble" focused on what we stand for, the second part was designed past-WWII but pre-UN, pre-NATO, pre-EU, and then continuously tinkered with along partisan lines, and over the past two decades there have been (and there are) repeated further attempts to keep tinkering.

Also, in a data-centric society where each citizen generates and consumes data, and influences the way national and local authorities cover their own roles through our current approach of political activism, there is some space for differentiating paths toward further evolutions.

We need also a new definition of "common good" that is inclusive but requires active participation.

And this implies probably a continuous contribution by citizens and corporate citizens of expertise and means that a leaner but more inclusive State within a renewed market economy within the EU framework would be unable to develop and keep up-to-date.

I liked to read about "utopias" since forever- in part courtesy of a 1,200+ pages book that browsed (and in part read) when I was still a kid, "Il Pensiero Politico"- and contained excerpts across a long list of philosophers, many of which was to "meet" again across the years.

In political activities, I met again Kant, and added other political philosophers, while at a European integration advocacy in the 1980s, and, on a more extensive and intensive way, on a few funny courses that found on the website of Yale (oyc.yale.edu) while living in Brussels, and followed in 2008-2009.

Some of the books that I re-read more often in that line were "Republic", "Leviathan", and of course "Utopia".

And liked also funnier ones, such as "Flatland".

Albeit I consider "utopias" also books describing alternative management methods, that often seems designed either for "fair weather" (e.g. read Ricardo Semler's biography "Maverick"), or written ex-post as part of the usual "survivor bias" (i.e. trying to turn into universals and show causality in a disconnected series of events that generated a positive result).

In Italy, we have a general distrust of the "greater good"- we are too focused on our own tribes, and leaders way too often tailor reforms on their own person- both in business and in politics and society.

I liked the old movie "Utopia" from Laurel&Hardy (also known as Atoll K)- the synopsis from from IMDB: "Stan inherits a yacht and a South Pacific island. Ollie and Stan sail there with 2 other men. They shipwreck on a new atoll and settle there. An ex-fiancee joins them. They declare an independent nation and problems arise."

Actually, if you are unwilling to read any of the books that listed across this article, have a look at least at that movie, or, if you prefer more modern ones, "The Village" or even either the 1960 or the 1995 versions of "Village of the Damned".

Again: reading about history, archeology, cultures, and Constitutions long before I started getting used to the number crunching side of implementing policy in the early 1980s really helped, as I had a rough understanding of the difference between a speech or a book style "Indignez-vous" or Piketty (that read in three languages, courtesy local libraries- I still found the original book I of Marx more interesting), and the complexity of political reality.

Since I returned to Italy, I had a three periods between contracts where prepared something else, and used the opportunity to recover and improve some skills, including by studying.

It was funny e.g. in 2012 to learn to cut wood while living in the mountains, and using my MP3... to listen to more than half a dozen of those courses from Yale about history and political philosophy that had downloaded before moving to the mountains for few months.

I listened to those courses before my travel to Berlin in November 2012 (when I wrote what turned out to be the first book that published- you can read it online for free), and after I returned in Italy in late November 2012.

Equally funny was, due to lockdowns from March 2020, to have the chance to assume that for few months I would be "benched", and therefore be able to follow a more complex curriculum to expand and update my data-related skills (started in the 1980s), but this time using exclusively open source and free resources.

Both on the business and political side actually "gave back to community" by doing what I did since the 1980s- contextual analysis and creating curated datasets and associated tools, and sharing it online (look e.g. at datasets on Kaggle and GitHub).

What is the impact of a data-centric society where each individual becomes, by interaction, both a producer, a consumer, and a (willing or unwilling) influencer on the behavior of other individuals and society as an aggregate?

Mutation- continuous mutation of what is relevant.

Shifting to the human side, I still keep hearing once in a while some talking about the human genome as if it were a unique standard valid for everybody forever, while there is a significant number of variations on a daily basis.

Being in a data-centric society implies being able to "tailor" to specifics with less overhead, i.e. less people needed to do the tailoring, once you define the framework, and continuously evolve.

I liked the preamble to the GDPR, as it was an interesting example of "boundaries definition"- you can read some selected articles (and a book) I published few years ago, or search within articles about GDPR.

Currently in Italy the discussion is again about changing the Constitution to alter the distribution of powers between leaders, but I still see a lack of a systemic view.

Even ignoring the XXI century data-related rights (which cover every single element of the interactions between citizens, between citizens and the State, and citizens and the environment), still any change should consider the overall change of the "framework", i.e. the electoral law and downsizing of Parliament, which could generate a de facto self-referential oligopoly that would have impeded new political forces to raise as it was in the 1980s-1990s and 2010s-2020s.

Somebody would claim that this could be actually a benefit, but, again, I prefer a shared consensus on the "commons", and then a freedom to evolve within the context of that framework.

When I was going around Europe on a weekly basis, while living London between the late 1990s and early 2000s, before shifting to Brussels, I always added visits to bookshops, exhibitions, museums, etc.

I wrote about Berlin in 2012: well, on the way back, I had an additional piece of luggage for books, and actually the excess luggage fee was higher than my return ticket.

I will skip referencing books that I purchased there about WWII and Cold War, as were mostly in German and probably not so interesting to many.

Instead, as I shared with a local friend, recently decided to add to my readings the re-read of a book in English from 1969 that found in a used bookshop along with others (probably a library dumped by those inheriting a house), "The Roman Nobility" by Matthias Gelzer.

What I liked about this book was that it was a narrative built on sources, not just the usual "trust me, I know better- and this is the story".

I prefer references to the sources, pretty much as I like references to the laws whenever I get a reply confirming or denying a right when dealing with bureaucracies- instead, in Italy, since 2012, often I get "trust us because we know better".

Also, that book shows the evolution of the balance of the distribution of power within the Roman Republic- I know that it is old, and contemporary sources too might have been biased, but, frankly, as I was in school in the 1970s, when history was taught in Italy in a highly "politically correct" way (all the negatives one side, sweep under the carpet any negatives that you dislike), I prefer contemporary bias from that added by later interpreters that filter out what they dislike.

Let's set aside the data-centric element while reforming the Constitution.

Why? The risk, due to the lack of expertise on the political side, is the routine Italian approach of finding a "friendly" who will turn into the exclusive source of truth, not the distillation of aggregate domain knowledge- hence, going up to the risk of embedding in laws something that really is a kind of "adoption" of specific choices, processes, technologies.

Still, a useful procedural change could involve enforced transparency and traceability of decisions- which would of course, require adopting solutions to make that economically feasible (i.e. more automation).

Anyway, just forcing to issue each and any communication digitally and digitally signed, and with references to the specific regulatory elements involved, so that citizens, directly or with their own advisors, could reply, would be a significant progress.

For major laws affecting rights, and not just "technicalities" (the latter being e.g how to label products and produce, the former being e.g. who can do what when how), it would be worthwhile adding to the Senate and Camera dei Deputati websites a "partecipative element" in parallel to the Commissions work, to help structurally collect material, and not just by invitation or structured organizations.

Why the latter? Because, as I shared e.g. during the definition of the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (in Italian, PNRR) on GitHub and via few articles since then, unfortunately the call was for society to contribute ideas to what should be inside, and instead many of the contributions were self-serving, and not just from businesses.

Adopting instead a bit of the old Wikinomics lessons learned could help avoid what has been increasingly the new legislative trend in Italy, shifting from the already annoying habit of issuing "skeleton" laws that then were "filled" by bureaucrats (sometimes generating issues I discussed above), to laws that start being "tinkered with" as soon as they are announced or even released.

Of course there will still be demands for changes, notably the habit since at least a decade to try to "push" within the government agenda parts of the political platform of the opposition that did not win the elections, by using the "silent majority" approach of filling up the squares to generate buzz.

Half-jokingly remember occasionally how, while living in Brussels, I saw some "professional protesters" who landed almost on a daily basis in a small spot nearby the European Commission, between two traffic lanes, but were then shown on TV as if they were a crowd: I always wondered if that was their job.

Reforms always involve a narrative: but many of the current narratives sound more like "Tik-Tok"-driven narratives that start with an idea, and then use the feed-back (presented as "observations") from the audience to create a change that never becomes a concept, while claiming to be a project.

Also in projects, I remember how sometimes my team members in the past said that, when there were changes in requirements, I kept renegotiating priorities while keeping steady on some points of reference, instead of losing track as other project managers did: but you need to have those points of reference, to allocate for changes within the context and associated priorities.

Or: it was my political and communication past that helped in "rerouting"- and earned me in Rome the nickname "robofaro" (a nickname about my family name, that means "The Lighthouse" and "robot") as... they said I never lost direction.

Again, it is not complex if you a) remember the "framing" priorities b) keep a communication channel with the business side to pre-empt issues or alert about potential issues and jointly define how to "reroute".

In my view, if you do not like to listen, communicate, say occasionally "no" also when that requires getting (figuratively) slapped in the face to save the project and keep the team focused on its work,...

... do something else, not the project or program manager or even the PMO: if you want just praise and just keep everybody everytime happy, then you are in the wrong business.

And it is not a matter of "methodology": whatever your approach, and whatever your domain, what I saw since the 1980s was the same (notably in recovery or phase-out projects).

If instead, you start the journey and then keep moving according to the evolving "wisdom of the crowd", your initiative actually risks becoming a Trojan horse for aggregated interests who influence those apparently independent.

You need to consider impacts: personally, for something as structurally changing as what has been proposed (i.e. expanding the powers of the President of the Concil of Ministers into a Prime Minister), would prefer an election focused on appointing a Constitutional Reform (the "Costituente"), as there are too many side-effects that would require a "retuning" of other parts.

But, of course, there are many, both in Government and opposition, that would prefer the current back-and-forth, as generally a "Costituente" would have to develop collaboratively a consensus- not really what is politically interesting when there are forthcoming election rounds (the European Parliament, some Regional elections, while many of the recent interventions sound as paving the way also for the choice of the next President of the Republic).

If this article evolved on the previous article about audiences, which covered both business and politics (as did the book "strumenti" published in late 2014), the next article will flip again to the business side.

As I shared this morning, I heard that locals have their own "theorems" on why this continuous swap- but it is a reality that since the late 1990s, when I was first living abroad, I was asked to come back in Piedmont to help recover existing activities or launch new ones: and the constant "fading to black" with delocalization of local businesses that I witnessed since 2012 (and was reported about since the late 1980s) confirms my assertion.

Or: there are still plenty of local financial and human resources that could steer the boat toward another direction, but drifting and tinkering seem to be the preferred option to avoid having to make choices- and maybe disappoint a tribe or two, something that would of course generate retaliation down the road.

I rather prefer to keep working on solving and building, and keep at arm's length tinkerers and gossipers.

Stay tuned!

_

_