Viewed 20019 times | words: 6332

Published on 2020-12-03 12:30:00 | words: 6332

This is the third article in a series- the introduction was here, and this is the first of two articles focused on a specific industry.

Despite its length, it is just an introduction to this theme- more about it in the future (and yes, the previous two phrases will be also in the next article).

What do I mean with "mobility"? Not just automotive or other transportation means, public and private- but also their interactions with the socio-economic ecosystems they belong to or get in contact with.

Within the previous article, "Going smart (with data): the Italian case - a tale of two cities, virtual and physical - Turin example", shared (many) doubts and (few) ideas about the present and future of our urbanization and its relationship with the surrounding environment.

Just to state again the point, as it will be useful also within the scope of this article: I disagree with those who say that COVID-19 will force a "return to the land".

In my view, this crisis will be used in such a way, notably by interested parties that already over the last decade tried to create both incentives to relocate elsewhere, and disincentives to stay in larger towns.

Including as part of post-industrial initiatives to increase the value of real estate within the historical centre of major Italian towns.

E.g. by increasing restrictions on private mobility unless you or your company can afford to have a vehicle compliant with the latest round of restrictions (changing every few years), and by trying to convert renovation in urban centres into a reduction of the number of households and "gentrification" to a point to make economically unsustainable for locals to live where they ancestors lived for centuries.

No, it is not an assumption: it is a statement of facts that was already visible in late XX century in places such as Florence and Rome, with people shuttling in and out of town on a daily basis, with commuting times similar to the ones that I saw in Paris while working there in the late 1990s.

As a French collegue told me: leaving too early in the morning to see his children before they went to school, returning too late in the evening to see them before they went asleep, and travelling each day between 1.5 and 2 hours a day- each way.

But in the XXI century we can do what was not feasible in the late XX century- it takes just a leap of organizational faith.

As expressed in the previous article, I see more than just a dualism between "urban" and "non-urban".

In Italy, we still have thousands of villages with centuries or thousands years of history, villages that deserve something more than the "suburban" moniker, and are nonetheless fully integrated with the leading town in the neighborhood.

The level of services that we are used to have as citizens would be incompatible with a new "Middle Age", made of a new form of rich castles living on the back of surrounding villages.

The XXI century, also without considering the current crisis, delivered a much overdue rethinking of a kind of "busybee stasis" that we had since we lost that stability that, in the end, a Cold War between two partners able to deliver a M.A.D. (mutually assured destruction) ensured.

We can instead rethink using technology e.g. to provide some services and healthcare in new "virtual metropolitan areas", evolving the 14 "città metropolitane" I wrote about in the previous article.

Evolving toward what? Toward a different model of governance- and the same applies for mobility, within the "evolutionary" definition that I tentatively shared above.

This article will talk directly about mobility (and, of course, automotive) only half-way through.

As before, following the "systemic" mantra that I keep writing about, I would like to share something about the environment XXI century mobility will have to be considered an element of.

What will I share in this article?

_ the unbearable lightness of old frameworks

_ an apparent digression to gaming and conspiracies

_ democratizing budgets and technologies

_ data intensive mobility and multi-centric decision-making

_ technology as an enabler vs. "control freak" attitudes

_ the new (data) social contract

_ an ecosystem of ecosystems- all unbundled

The unbearable lightness of old frameworks

This series, as many of the articles on my website, is as much about data as about people, companies, and societies at large.

In the XXI century, all those elements are interacting and influencing each other, more and faster than ever before.

The previous phrase, is, frankly, a XXI century platitude worth of a La Palice- or one of the many "philosophers" that seems to be around every corner, online and offline, as well as assorted futurologists good at "forecasting the past" (or, at best, the present).

The theme is worth a really long introductory set of sections that only apparently has nothing to do with the subject of this article.

In the old XX century Cold War world, e.g. the one preventing exports of high-tech to COMECON countries, high-tech was complex enough to require advanced facilities, often physically large, and therefore was relatively easier to differentiate between what could be "consumer", "business", and "affecting critical infrastructure and security"- at whatever level.

Or: "control" and "governance" were relatively easier.

Already in the late 1980s we saw a blurring of the lines between commercial and potentially critical impacts of technology, courtesy of the PC revolution (e.g. see this 1987 short article).

This article focuses on mobility- but, as in a question that I asked earlier this week during a webinar on dual use of drones, I see this a matter of what in other environments is called "doctrine".

I would like to be blunt.

We have to get rid of old paradigms: nowadays, the democratization of even complex technologies (ranging from IoT to Machine Learning to building your own supercomputer-on-demand by using cloud computing at scale) requires a different approach to both monitoring an development.

In a later article, connecting all the others in this series, I will share my journey through business computing from the 1980s until the early 2000s, and how that influenced and supported my business activities and partially altered my perception of social and economic realities vs. what I had learned as a teenager in European integration advocacy (specifically, federalist) as well as interacting with the Turin secretaries of the youth organizations of an array of political parties from the left to the right (what used to be called in Italy "arco costituzionale"- from the Communist Party, PCI, to the Liberal Party, PLI- in between PSI PSDI PRI DC).

But, for the time being, I would like to share a technology-oriented digression, using as a case the humble Playstation 2.

In the early 2020s, many forget of the curious case when Saddam Hussein's Iraq ordered Playstation 2 in the early 2000s, thousands of them.

An apparent digression to gaming and conspiracies

I know that many articles from "gaming communities" and "security experts" discounted the issue of a potential re-use of the Emotion Engine (the "brain" of Playstation 2) toward different uses, but I still beg to differ.

In business, I am used to see the resources available and the issues at hand- and act accordingly.

Just because an object is supposed to be used in a specific way, that does not imply that cannot be repurposed.

Moreover, when objects increasingly depend on (dumb, smart, artificial intelligence) software to deliver most of their statutory purposes and services.

As shown many years ago with the first robots, and the whole "jailbreaking" movement about iPhone and Android smartphones, nowadays "repurposing" is within reach for any consumer.

Actually, eventually smarphone producers and Google introduced a feature to turn yourself into a "developer" embedded in your own mobile phone software: you just have to get to a specific part of the settings, click few times, get a warning that you are about to access the developers' mode, and then, few clicks away, you are able to modify the behavior of your smartphone.

There are various examples of how gaming machines, specifically the Playstation, could be repurposed (e.g. see a 2020 article), but I would like to share a couple of personal experiences and ideas.

In the late 1980s, while working on Decision Support Systems, I remember being told about an expensive "vectorial facility" that was available nearby Milan, Italy- we went nowhere (or, at least, not that I know), but was again to hear about it few years later, while working on other subjects (selling methodologies and associated cultural and organizational change services, as well as supporting with the former the "business software packages" and "computer aided software engineering" suite of the French company I worked for in Italy).

But my time with PROLOG and Decision Support Systems in the 1980s came back to mind when, in the early 2000s, while living in London, attended a presentation by Sony engineers as part of an IEEE series.

The presentation was on the architecture of the Playstation 2, specifically its Emotion Engine.

From the wikipedia page:

"The Emotion Engine consists of eight separate "units", each performing a specific task, integrated onto the same die. These units are: a CPU core, two Vector Processing Units (VPU), a 10-channel DMA unit, a memory controller, and an Image Processing Unit (IPU). There are three interfaces: an input output interface to the I/O processor, a graphics interface (GIF) to the graphics synthesizer, and a memory interface to the system memory."

Technicalities- but the presence of a vectorial facility made for some interesting uses, and also the Sony engineers said that they were surprised that few used it.

There was a string of articles on the sudden purchase from Saddam Hussein's Iraq of a large number of Playstation 2 units, followed by news that in Japan had been decided to consider to require an export license for "dual use".

Even more technical details:

"The CPU core is tightly coupled to the first VPU, VPU0. Together, they are responsible for executing game code and high-level modeling computations. The second VPU, VPU1, is dedicated to geometry-transformations and lighting and operates independently, parallel to the CPU core, controlled by microcode. VPU0, when not utilized, can also be used for geometry-transformations. Display lists generated by CPU/VPU0 and VPU1 are sent to the GIF, which prioritizes them before dispatching them to the Graphics Synthesizer for rendering.

The PS2 is the earliest known commercial product to use ferroelectric RAM (FeRAM). The Emotion Engine contains 32 kb (4 kB) embedded FeRAM manufactured by Toshiba. It was fabricated using a 500 nm complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) process.[3]"

As befits such an occasion, on 2000-12-19 an article appeared: "Sources in UK intelligence said the reports were "nonsense" ... It's also very unlikely that bundling any number of PS2s together would actually work, as it would be extremely complicated to have a number of processors accessing shared memory and splitting up the computation. The complex software required would take years to develop."

In the "Yes, Minister" tradition, an official denial is a confirmation of sorts.

But, as shown in the 2020 article I linked above, it was possible, attempted, and then even scaled up with the next one.

Actually, while living in Brussels, I purchased a Playstation 2 (bartering a new "slim" model for an old bulky one) and...

...the Sony Linux software kit to develop software using the Emotion Engine- and I still have within my files sample code from enthusiasts that actually used the vectorial side of the Emotion Engine, plus the hardware in storage in Brussels.

And all our Bitcoin or Machine Learning are rabid users of the power of computing resources created for gaming, scaled up into something else.

As for the phrase "it would be extremely complicated to have a number of processors accessing shared memory and splitting up the computation. The complex software required would take years to develop"- well, more than a hint of racism, there.

Democratizing budgets and technologies

If you search online, you can see that some enthusiastic computing hobbyists joined a number of Raspberry units (cost down to the low 10s of EUR for a model zero unit fully equipped, and slightly less than 100 for more powerful models) or Arduinos to obtain computing power that would have been unreachable to most companies until few years ago.

There are now and then temptations akin to the Clipper chip initiative, to "clip the wings" on technologies- but, again, it is an obsolete approach to a new reality, akin to a Maginot line built when it was already feasible to simply go around it.

We need more dynamic and proactive continuous monitoring and preventive approaches that adapt to the environment and the interaction between its components- not a pre-emptive "dumbing down" based on yesterday's experience (we did that already with way too many applications of the "Maginot line" paradigm).

And, yes, all this requires more data, not more bureaucracies.

Alternative? Adopt the old "clip the wings, build embargos" approach- and see your own economy and society fall behind, and turn into a data producer and service/products consumer, with a massive transfer of both wealth and control to other societies and economies more able to adapt to a different model of governance.

The democratization of technology and computing power was supported by a massive externalization and delocalization of high-tech, sharing worldwide the building blocks of more advanced technologies.

The genie is outside the bottle, embargos now would just be a figment of imagination that would actually inspire focusing on more innovation to circumvent them.

Look at what happened with 3G and 4G: countries that, such as European Union members, had heavily invested in 3G infrastructure and services, never managed to have customers pay off those investments by e.g. using MMS or Video calls, while other countries that lacked that infrastructure jumped directly on 4G, or expanded Internet mobile, and that enabled pure service providers to just build and expand services using the high-speed Internet traffic- and we obtained video calls or MMS via WhatsApp, WeChat, Instagram, etc.

One of the side-effects of cloud computing at scale and on-demand (from various players), and the open source paradigm shift, is actually that both hardware and software are affordable not just from an economic perspective- we are "scaling up" also human capital embedded in software and hardware.

If you want to deliver new services, you do not need anymore to invest in infrastructure, and have a huge vertical organization with thousands of employees that then you have to be able to manage before you even start delivering your new service to your customers.

It is a "pay-as-you-go" and "scale-as-you-need" world, where new technological entrants on the market do not need decades to spread their services- but I shared charts in the past, and you can google phrases such as "technology adoption speed" to see an infinite number of variants.

Join to that also the shift from producing software and solutions to be used within office environment, to "cloud first, mobile first" applications, i.e. assuming that you do not have a physical infrastructure, and that mobile phones are actually only smartphones with computing power that exceeds many computers.

I give you again a small personal example: while, between March 2020 and June 2020 during the first COVID-19 lockdown in Italy, followed offline and online training on Machine Learning, I tested also some ideas that I had first applied in the late 1980s using a multi-dimensional Decision Support System model building system and other technologies, and saw that, actually, something that back then required extensive business domain knowledge as well as tool-specific knowledge, could now be learned and give some results by going to the equivalent of "Cliff Notes" (in Italy, "Bignami").

In the 1990s, doing most of those computations still required having access to PhDs- now, anybody with decent business domain knowledge can actually, after spending few days (and I am not talking about myself), produce models able to learn from data- as it still critical to understand what data mean, for most business-ready applications, and selecting the right data.

On "right data", I published a couple of books- you can see summaries here- relevant data and consent data.

Yes, to e.g. shift that "data processing engine" toward an optimal architecture that may eventually be delivered into, say, an office desk lamp able to read documents and highlight key performance factors for your business unit...

...still requires "technical" experts.

But, budget-wise, we are talking about peanuts vs. peanuts plantations budget sizes.

I remember how, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, apparently to streamline activities, ICT departments of major banks in UK and elsewhere had released to the Business side small-sized ICT budgets that required no intervention from ICT, after complaints that ICT departments were too slow to react, when what they needed maybe was to just develop now some number crunching.

Side-effect: external suppliers, in order to bypass the filter of ICT, developed a range of "Software As A Service" (SaaS) solutions that had two characteristics.

First, a monthly cost well below that budget threshold for approval

Second, presented, packaged, delivered in terms of business process/solution, not technicalities.

Some required to upload/download a file to receive in exchange an assessment.

If you are from a security or ICT or audit background, you can immediately see the danger: who is going to vet the technical and security viability of these micro-suppliers? Or the "chain-of-custody" of data? Certainly not the business users.

And how does this all relate to automotive and mobility?

Data intensive mobility and multi-centric decision-making

Welcome to data-intensive mobility.

Few days ago, in one of the communities on Kaggle (a data science community and "testing ground" platform using Google services) I shared a comment on something I think we are not yet accustomed to.

Say- any Microsof Windows 10 user is now accustomed to the concept that yes, the computer is yours; but yes, you, the user, aren't the master of the computer- Windows 10 is, and routinely asks your support...

It is a joke on the same line of one made long ago from the CEO of a car maker in reply to Bill Gates, but it is actually an element that any user of any device that is "personal" got used to in the first two decades of the XXI century.

The more data-awareness we add to our devices (e.g. a car able to park itself, a mobile phone adapting to the environmental light), the more we do not have have anymore "devices"- we have "systems".

And we, the people, are a component of these "systems".

When a car adapts to your body when you sit down, and adapts to your driving style to avoid mismanagement of your car, in my view we are closer to something else:

I, Cobot (paraphrasing Asimov)

I heard yesterday evening an interesting webinar on the future of space exploration and the business of space, and some discussion about the old "cyborg"- i.e. the physical integration of machines within humans.

Albeit now it is shifting toward something else, i.e. accepting that, as reminded yesterday by Padre Paolo Benanti of the Pontificia Università Gregoriana, if we are to go into space development and exploration, Artificial Intelligence will be needed to do with 10 people what would need 100, as sending into space hundreds on each mission would not be feasible.

And the same, actually, applied to many levels of automation that I met since the 1980s while working- ranging from physical automation (e.g. manufacturing robots, and eventually manufacturing cobots doing the "heavy lifting" to support their human co-workers), to software automation of business processes.

Automation that we often ignore or take for granted: look at 1940s or even 1950s movies, and see how activities ranging from connecting phone calls to reporting the position of airplanes on a map for air traffic control involved countless people.

We are still talking about cars as if they were independent vehicles- which is marginally true only when we are driving on an empty road outside town.

Our cars since decades are stuffed with sensors, sensors that in more recent cars are influencing the "behavior" of each vehicle.

Vehicles that, now mainly potentially, in the near future on a continuous basis, will be "broadcasting" information, and collecting information from other sensors that will be where they will be moving through.

Actually, as I shared in a previous article, recently in Turin was announced a CCTV system that could be complemented by individual citizens' smartphones, coupled with a "gate" system in central areas that could switch hybrid vehicles to electric propulsion.

Leaving aside technical, security, privacy issues (just to name a few), one of the weaknesses of this approach is that, again, assumes a centralized "control room", and hints at its extension toward an all-knowing "city as an airport" approach.

An Italian obsession that reminds Bentham's "Panopticon", coupled with a social structure that reminds Hobbes' "Leviathan".

Technology as an enabler vs. "control freak" attitudes

As I wrote in previous articles, XXI century technology is to be considered an "enabler", if you want to reap the benefits it can deliver- i.e. you create the enabling factors based upon a general strategy, but then, beside controlling a degree of "fair play", you cannot really know which technologies will emerge.

Now, Italy is perfectly capable of surfing the latest technological wave, but we have this lingering obsession with central control, coupled with a culture that you can do only what is already authorized.

In Italy, whenever there is some innovation from abroad, somebody states "we had the same before".

But almost never we ask ourselves "why" it id not develop into what are known as "unicorn".

I will give you two personal examples (on a much smaller scale).

First: in the early 1980s, my Sinclair ZX Spectrum computer that I purchased by selling used book received sofware via... audio cassettes.

As my father had some radio shows on FM radio, I proposed to set up a radio show to broadcast software and discuss about technology, with also some music etc.

Eventually, i pulled the plug from the idea, as it was taken over by the radio manager who simply wanted to add so much sponsoring to make it impossible to bear for the target audience.

My concept was to first get the audience, but as I was just a teenager barely turned 18...

The funny part? Later, somebody else in the USA announced the same, and in Italy... was heralded as a novelty.

Second: as I shared recently on Facebook and Linkedin, in the early 1990s, after leaving the Italian branch of an American company, shifted to the Italian branch of a French company.

Well, what happened was funny: for both companies, in different roles (the former, on Decision Support Systems, the latter, on methodologies and associated training and change services) I was almost on a daily basis in a different town, with either customers I followed directly, or customers followed by colleagues where my expertise was required.

The funny part was that I had left the previous company so that I could be "residential", and the Turin offices of my new company were just in the same building complex of the new offices of the Turin University, so that I could work-and-study, and complete my degree.

Well, I soon shelved the latter- as, after one month of induction training in Paris, I was bumped up, given a new fancy title for a new business unit, as well as an apartment paid by the company but... in Milan.

In the 1980s, I had received by my first company a Compaq "brick" luggable computer (about 10kg), then a Toshiba 5100 with a plasma screen (same weight, smaller size), because I had often to crunch numbers.

Then, I purchased my own portable PC, an Olivetti with two 3" floppy, no hard-disk, as for few months in 1990 was a free-lance on cultural and organizational change, but then saw that in the French company the secretarial pool used Apple Classic computers.

As I was given eventually an apartment nearby the office, whenever I returned in Milan at night, if I had to travel the following day, I went at night in the office leaving my scribblings (there was no email service yet; no, I had not yet a mobile phone- I purchased one as soon as the GSM service was set up in Italy, few years later).

So, I purchased an Apple Powerbook 100- which was, actually, an Apple Classic converted into a laptop by Sony.

It was an improvement, as I could leave a floppy- but wasn't enough, as sometimes I had to send something.

Therefore... eventually purchased a fax/modem.

Why I had not purchased it before? Because, in Italy, having a fax/modem in your computer converted you into a... post/telegraph office, and you had to pay an annual fee that was more expensive than the purchasing cost of the fax/modem.

If you read previous articles on this website, you know that one of the themes that I follow is the so called "Edge Computing", that could be described as "processing where data appear".

It is the technological equivalent of what I saw on Decision Support Systems and quality since the late 1980s: where something happens, there is where you have to filter and intervene, as it is where the "operational" knowledge is available to understand data.

The further up in the consolidation and hierarchy you go, the less details generally you have, and the more assumptions are made on where those elemental data should be "pigeonholed" on their way up through the usual routing cycle of data that becomes information, information that becomes knowledge, and, for those so inclined, knowledge that turns into wisdom.

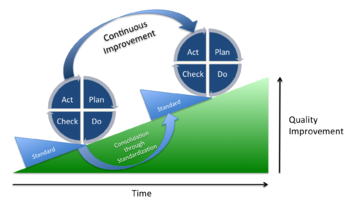

I am more down-to-Earth, and I rather consider the traditional "Deming Cycle" (Plan-Do-Check-Act), but in its "continuous improvement" version, as in this picture from wikipedia

It is a journey, not a destination

With technology removing the need to invest ahead of time into technological infrastructure (you can use it when is needed, paying a "per-use" fee or a low-cost subscription), that nice "continuous improvement" image should be converted from its two-dimensional chess to something akin to the 3D chess board of Star Trek, but with a more dynamic structure.

Or: when the "basic infrastructure" is an equalizer (i.e. anybody can afford the basics of Internet services, both as a consumer and as a provider), it is something ludicrous to assume that you can pre-empt new services with your own all-knowing team that will filter anything new offered.

What you can instead do is to think in terms of "interoperability", "quality of service standards", and, talking about data, a kind of "data social contract".

The new (data) social contract

Whenever a technology becomes widespread, it is normal that, eventually, there is a convergence to ensure what is called "interoperability": no matter which supplier you select- you need to have at least standards to connect different components from different supplier.

But data isn't like an electric plug, requires something more.

So, GDPR has to be considered as an element of a new "data social contract", a kind of litmus test to say: do what you want, provide the service that you want, but these are the minimal standards you have to adhere to, if you want to do your business here (you can read more about my position and examples on GDPR: a book, articles, etc).

Think again about that picture on "continuous improvement", but multiply it by tens, hundreds, thousands of similar cycles interacting with each other.

Now, I think that you can agree that having a single, ex-post, "traffic cop" would be delusional.

Probably, in the new "data social contract" you need both "innate" self-regulation, and some "antibodies" within the "data ecosystem" against mistruants (again- e.g. a "GDPR within the infrastructure"), not the Byzantine filing and appeal process that we have now.

When you consider the "new" mobility from a data perspective, and when you add the "cobot" element I wrote about on Kaggle, you have to shift your mindset toward something else.

It is, as you can expect, a "systemic" perspective, but with a twist.

Nowadays, companies are shifting from talking about their "philosophy" to talking about their "ecosystem".

Well... I do not know about you, but, personally, I do not see myself as "belonging" to a proprietary ecosystem.

Yes, there are "technology fans" such as some Apple zealots who use no software no product no service unless is provided by Apple.com.

But, frankly, within the new "data social contract" I talked about, what I think and will develop later in other publications is that we have an ecosystem of ecosystems, mutually interacting, and mutually affected by interactions.

You see a car.

You see maybe a car with an Internet connection and an on-board entertainment system.

In the future, you might see a car with specific features tailored on you.

But, as I wrote few articles ago, if you shift toward a different concept of ownership, you will not purchase a car- you will get a subscription and time with a car, or "car-on-demand".

Albeit some, probably on the higher-end of the spectrum, or that use it really often, will find more interesting existing forms of ownership (from purchase to full-service, to various forms of leasing).

In the one-demand yet data-centric world, you will expect you data-aware car to "remember" how you liked it.

So, also for health issues not made visible by COVID-19, maybe in the future our (temporary) cars will not have inside textiles, but materials that can be more easily disinfected from one occupant to the other, and "live" surfaces that will change the appearance to what we like.

Say- if I like model A, whenever I will "summon" a model A, the model A that will arrive will "receive an advance broadcast" of the settings has to adopt while its moving from its current location to where I am now, so that, when it arrives, it will be "my" car.

Obviously, I am talking about a not-so-distant future where e.g. cars with passengers will be semi-autonomous, but cars in transit will be fully autonomous.

Short-term, the same approach could apply also to cars that you "reserve" at a "parking location": if the app on my mobile phone states that the car is 5 mins away, as soon as I reserve it, it can start "charging" my account for the "customization" profiling costs, so that, when I arrive there, it is ready; and, if I change my mind, will simply re-adapt to somebody else.

While this small detail? Well... the first electrical cars had also a "free recharge" service- and some entrepreneurial "e-currency miners" simply... put computers on the car, and then used the free electricity to "mine" digital currency for free...

...so, in this "data social contract" future, you have to take a step further.

An ecosystem of ecosystems- all unbundled

Yes, an interaction between ecosystems.

But, talking about data, we need to rethink (some companies already did) to each one of our services and products as "unbundled"- you can buy a product or a service, but then you are billed (or credited) by parts.

Nothing really new: I remember being told, in the late 1980s, how a German car maker had de facto applied Womack's prescriptions on "customization" (see a review of its evolution here).

You did not purchase a finished car- you got a car, but then had to select seats, interior, wheels, etc.

Now, this is technically feasible with any product or service.

If it is not done now, it is simply because not enough rethinking has been done by many companies of their products, services, and, yes, internal processes, systems, organizational structure and organizational culture.

We have to get rid of the internal fiefdoms and rivalries between e.g. finance, marketing/sales, production in manufacturing companies, if you want to be flexible enough to really have an "ecosystem".

Because even within the confines of a single car- or vehicle-maker (on sea, land, air, space), an ecosystem that sees a monolith on the supplier side is not going to be an ecosystem.

In an ecosystem, you need to have multiple potential patterns of interaction, to enabled "adapting"- e.g. evolve your products while they are still in use and production, but ensuring continuity to those already on the road.

Also, if you want your own organization (or yourself as an individual) to benefit from the interactions with other ecosystems, you need to have some degrees of freedom- otherwise, you are in for a war of attrition.

In the new mobility, I think that of course vehicles will interact with the environment more than they do now, and each vehicle will interact with its human "cobot", by sharing advice, suggestions, or even asking feed-back within decision-making patterns- an evolution of what some on-board GPS can do (suggesting different path), but based on preferences learned on the job, not set manually by getting through hundreds of options.

Flexibility and adaptability are key features of any ecosystem that is able to ensure its own survival.

Probably, we should see vehicles, citizens, cities through a different for of "Gaia" approach (search on the web- you can find plenty of material).

Whenever a vehicles will move through a city, or between cities, will have to interact with multiple ecosystems, and this too could generate an "economy of the ecosystems"- a transactional economy, or something focused on "long-term relationships": a matter of (social, individual) choices.

There is obviously another element, that I discussed in previous articles: cross-modal use of vehicles.

If you want, when you ask GoogleMaps for directions, it is already "cross-modal", but not so smart, mixing pedestrian, public transport, private vehicles, etc.

In the future, in reality a single day in life could be cross-modal and built around the optimal interaction of various ecosystems, also to enable each one of them to "adapt"- adapt capacity, performance, evolution...

This article is, as you probably understood, just an introduction of what could a future mobility evolve to.

I discussed in previous articles how the automotive and vehicle production industry could evolve, and might well eventually expand on all these themes and summarize in a coherent whole.

But, for the time being, I hope that I shared enough doubts and ideas to help you make your own choices.

Stay tuned.

_

_