Viewed 11060 times | words: 1257

Published on 2020-01-16 07:55:08 | words: 1257

First the latter, as I am just "taking a loan" from a course on sales that I followed in London over 30 years ago.

The story goes that, while preparing a gas pipeline, somebody went smart, and to speed up the process new massive, pre-built sections were shipped by sea.

Trouble is... nobody had considered how much weight could be lifted by the cranes at the port of destination- that promptly folded when the first shipment was sent.

The acronym stands for "Oh Sh** I Never Thought Of That".

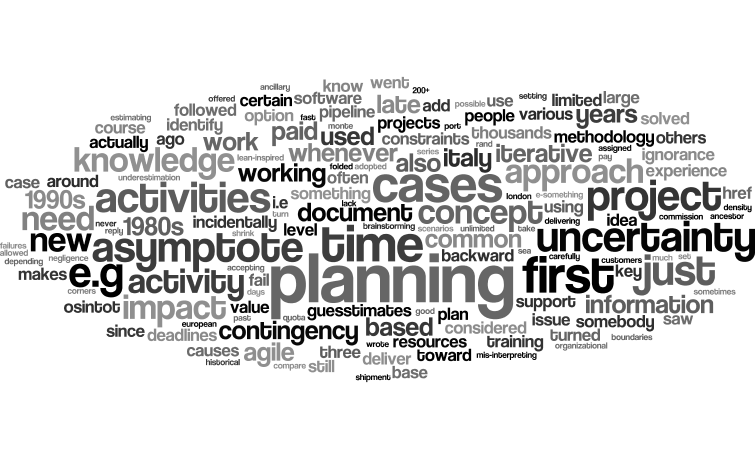

By experience and observation, e.g. the projects I went around to support in Italy in the late 1980s, plus what I obtained from other accesses to company libraries, my concept while delivering training and coaching project managers in the 1990s was simpler (and confirmed by my activities there and over the following over 25 years): it is a matter of convergence.

I considered that estimating was akin to working toward an asymptote (at the time, waterfall was still common, i.e. first think, then document, then do, then verify, then document again, then deliver).

A typical case of asymptote planning is when you have the end date, and have to work backward, as in the the 200+ pages fictional compliance programme described at the link.

Actually, as I wrote in the past, in those cases sometimes I still brush up my PERT skills, and go pen-and-paper (well, with a spreadsheet) and use that tool created to manage a nuclear sub project.

Working backward, you need not just to identify how long each activity will take, or which activities should follow, or which activities could be done in parallel to others to "shrink time" (allocating more resources, of course).

You also need to know which "buffers" you can have before and after each activity.

I am afraid that, in theses cases, those mis-interpreting "iterative development", "agile", and "DevOps" as "fail quick, fail fast, do it again" are probably thinking about a world of unlimited time and resources.

It is true that in some cases might work (e.g. in Italy we are used to deadlines with more than one round of procrastination).

An even more critical case is when you deliver what in Italy is called "chiavi in mano" (literally "turn key"), as I saw since my first large project planning experience (1986, few thousands man days, for a software project, based upon a methodology derived from hundreds or thousands and mimicking a bit what was the COCOMO 81 but with a different knowledge base).

You are to be paid a fixed-price but comply with a certain number of constraints.

Obviously, the key then is contingency planning (in the 1980s, I was used as per methodology to add a certain quota based on complexity), but it is funny when you receive offers that have contingency on contingency and, for good measure, add a Monte Carlo with three possible guesstimates...

...not really something that makes sense, frankly, as how could you budget and control? Moreover, that level of uncertainty usually makes moot of those guesstimates, at the first issue generating impact on costs or time.

Usual side-effect to stick to the deadlines: cutting corners, hoping (and in some cases striving) to push the issue downstream, after the warranty period ends.

To avoid the OSINTOT (surprises) you would need no uncertainty- but no uncertainty implies waiting until all the information is in place.

Instead, often the concept was to evaluate options based upon limited information each option (including when they were actually too new to have an historical base to compare with), and then "converge" on estimates by reducing the level of uncertainty.

Also when, in more recent years, people worked using iterative (late 1980s-early 1990s), then various lean-inspired and agile approaches, often the impact of the unknown is not solved by simply splitting what you do not know into segments.

What is the impact of lack of knowledge?

Just to stay on pipelines, a 2008 research document on pipeline failuresreported that these were the first four causes:

36% Insufficient knowledge

16% Underestimation of influence

14% Ignorance, carelessness, negligence

13% Forgetfulness, error

Therefore, in effect, the top three causes could all be solved by planning and its ancillary activity (training).

Incidentally, it is a paradox: the "lighter" your approach (e.g. lean), the higher the knowledge density required to be able to cope with uncertainty.

In some cases, e.g. while I was working in the late 1980s to design Decision Support System models, using the iterative approach (an ancestor of various "agile") implied starting with the definition of the perimeter and "framework of objectives", setting time targets, and then accepting to work... toward an asymptote, i.e. continuously improving each element of the model, as only interaction between elements defined the actual constraints.

My approach since then was to ask customers to pay for a feasibility study, something common in physical engineering but not so common in consulting or software projects, back then.

The value? Depending on the information provided, but generally, if it was just an "idea" or "concept", my reply was an outline for a series of brainstorming sessions, structured around a kind of Delphi whenever there were too many people involved (to generate consensus on an option between a limited set of scenarios and formalize it).

Incidentally, I saw a similar approach used by RAND and others in Brussels when I attended workshops organized by the European Commission on e-something, over a decade ago (time flies).

In the 1990s, the reaction from my prospects was that I was asking to be paid to tell them what I would need to paid.

My riposte was simple: I was helping them to define the boundaries of what they needed, and then they were free to use it with somebody else.

When the target was a larger body of activities (e.g. a new service, a new relatively large project, an organizational change), I offered to discount the value of a variably part of that activity if they then assigned us what followed.

There are other planning paradigms, but also in those cases, I adopted my asymptote concept: and that allowed to reroute activities whenever some risk turned into certainty, affecting the carefully designed plan.

As I like to remember whenever discussing planning and being told that it is a waste, if you have clear ideas (or, just opposite, when you have no idea), supposedly quoting a general turned president, it is not the plan that matters, but the planning exercise (that enables you to identify the degrees of freedom and weak links in your knowledge/execution chain).

_

_