Viewed 8610 times | words: 3135

Published on 2019-11-10 | Updated on 2019-11-11 07:04:13 | words: 3135

Data. More data. Even more data.

But this will be short article. A picture is worth a thousand words, and therefore... I added four to this article.

More or less 25 years ago, while designing and then prototyping a new application for the distribution of knowledge based on the "subscription" paradigm, I used to say that we were already subject to "infoglut"- information gluttony.

We collect so much data, that we risk doing routinely what I already in 2003-2005 had reported as "old story" within an online e-zine on change: so much data, that those who could make sense of it all usually, due to the time-consuming technologies available at the time, were simply relying on some who where relying on some who... you get it..

The 1990s promised to enable management (from low to top) to have "data at their fingertips", to enable data-driven decision-making.

After DSS in the 1980s, I was on the data warehousing and business intelligence side both from from the customer and the supplier side, a parallel line to my other activities, due mainly to contacts from the 1980s in Italy and abroad calling me to join on the "pre-sales", "solution engineering", "negotiation", and "pilot project" phases of business intelligence and data warehousing.

Those roles implied having the chance to actually work in many industries and on different environments, as well as on project that back then (but also until recently) weren't the ordinary target for those tools (e.g. designing organizations).

One of the most interesting lessons was, of course, the power of "context".

Always skeptical of "best practices" applied across the board in business, due to my past interests in cultural anthropology, archeology, and politics, were it was easy to understand how much the specific environment constraints and balance of forces could turn a "best practice" into an attempt to fix a square peg in a round hole, business gave me plenty of examples where adapting had to happen before adopting.

What do you need to do before you adapt?

You need to understand.

Now, fast forward, and we live in a world where anybody is providing or receiving numbers and data.

From individuals looking at a rating for a restaurant or movie before choosing, to companies or civil servants doing a vendor evaluation, we seem to trust somebody else's answers more than our own.

Actually, often assessments are still done, but just as a "quick and dirty" rota learning exercise, after everybody involved in a decision already converged on an idea, solution, choice- based upon somebody else's information.

If it were only for personal choices or company choices- it would affect those who are actually footing the bill.

Unfortunately, as I wrote often in past decades (well, longer than that), beside providing statistics and benchmarking our own states with other states, in Italy we often import laws, stock and barrel- and then tweak after the first implementation is a "Frankenlaw".

I checked today, and it still seems that the most read article on my website is an anglo-italian post that I released few years ago, about industrial policy.

You can read it in Italian and English here: Per una politica industriale che veda oltre le prossime elezioni #industry40 #GDPR #cybersecurity / For an industrial policy that survives election cycles #industry40 #GDPR #cybersecurity

Currently, we are again in another round of "let's reinvent ourselves".

So, I would like to discuss (and highlight quantitatively) a small element that most politicians, industrialists, researchers that I heard and read in Italy seem to forget.

The proposed industrial policy guidelines seem to be oriented toward "green economy", "circular economy", "industry 4.0", etc.

Yes: if there is a buzzword, we are all for it.

At least on the drawing table, or when preparing a law- implementation is a different beast.

Also in my job, or when supporting customers on new initiatives or, in the past, to prepare business and marketing plans for customers and startups, I always used statistics and data from more or less reliable (or with a clear bias that could be filtered out or accepted) from third sources.

Nowadays, with "open data" (that I consider a side-effect of the late 1990s "push" for e-government and transparency by OECD, notably for multinationals), frankly if I compare with the 1980s and 1990s, I can do at zero cost what two decades ago required expensive software licenses and an intermediary providing a database that might actually add "noise" to the data.

I will later publish some other articles about other initiatives in Italy related to those "trendy" words listed above (and more).

For the time being, while I am still in Italy, I read routinely Italian newspapers- and the commentary on proposed new laws or new development lines sometimes sounds quixotic.

I reported already in the past how e.g. the Turin Chamber of Commerce or the Turin Unione Industriale or Milan Confindustria are quite well aware that most Italian companies aren't just owned by a family and managed by a family, but are not even "small" as per EU classification.

Our companies, according to official data, are small- albeit increasing in number.

As I worked across Italy between late 1980s and late 1990s (before moving abroad), and then in this decade explored and discussed more than once with business contacts from across the country, I think that considering a company size as an aggregate is more appropriate in other countries.

What is more interesting for me is the size of the individual local unit, as this actually delivers a better picture of a country ability to manage the scaling up of businesses.

Specifically: having "training-on-the-job" to breed talent for scalable companies requires having people involved in environments with various degrees of complexity.

If you get managers used to, say, manage 5-10 people, often in Italy this implies micro-management, person-to-person continuous contact, etc.

How do you expect them to be able to scale up to manage, say, 1000 people? Using the same approaches? Or just by reading books?

Our policy-makers over the last decade unfortunately have been importing way too often alien legal frameworks that imply a different social, cultural, economic background.

Then, overlapped "modern" digital transformation on top of our pre-industrial business culture, where the small size of our companies enabled flexibility, but at a price.

Our companies often lack the structure to be able to aborb novelties- also when it makes sense, and therefore end up in a feeding frenzy.

Whenever something becomes "trendy", there are some incentives, and companies end up buying what they do not need, or buying what they need, but lack the resources to rethink their own processes and restructure.

A typical Italian approach to change and innovation derives from this "trendy push": to get whatever the trend requires, and then assume that it would deliver value.

Then, either ends up doing what was doing older equipment, or ends up being underused.

Decades ago, in Italy there was a special incentive to create a company website: Italian colleagues told me how a "cottage industry" developed, "pushing" e-commerce websites even to one-shop backeries, knowing that they will never use it, just to "share" the incentive.

I saw in the past this "rule" apply to computers and machinery, and curiously there is another side-effect.

As businesses are unstructured and there is an endemic lack of resources integrating the knowledge of processes and company with the knowledge of new technologies, successes are often due to "Sturm und Drang".

In few cases, "Sturm und Drang" implied that yes, the company owners enthusiastically adopted new technologies, but forgot that they were entering an investment cycle with a shorter obsolescence cycle than those they were used to, and therefore should have at least checked two elements.

Specifically: if the lifecycle of their investment was aligned with their market.

Or: what is the point of investing on equipment to be used with a customer to support a new process, an equipment whose investment will make sense with 5 years of additional revenues, when you haven't assessed the risk that the 2 years contract from your customers is just a "stop gap" and not "a first 2 years"?

Actually, while living in London two decades ago, I remember in the early 2000s, after yet another railway accident, articles discussing how one of the issues was the flipside of this situation.

Or: 3 years contracts given to companies to manage a line, but with a commitment to maintenance that required investments that would be recovered in 10 years.

I do not if that was true, but the solution in such a case is usually to "pad" the contract value to cover for that gap- or end up doing as the company that did a famous leaseback in UK for public buildings: grab the contract, extract the value, and when money is out... pull the plug or ask for more money.

Sustainability is often considered mainly a "social" issue- but should be really considered a business issue: any initiative has impacts on costs and revenues, and any investment too.

You can read details about those concepts at the UN website, or the Eurostat one, or even just browse an online book by Eurostat.

But I will write more about that in the future.

The introduction above is a description of some cultural differences, but, as I started last month, at the end of this month I will release data extracted from official statistics, to support (if you are interested) your own assessment.

For the time being, I enclose just few charts.

Now, all the preamble about "small size of Italian companies" was really to lead to this point.

If you have small companies, but few here and there have hundreds of employees and are able to support a structure to develop management talent, that is fine.

But if you have small companies, and when they grow they simply "clone", and create units that are as it was the company at the beginning, you will almost never develop the ability to create anything more than "functional" human capital, i.e. your managers probably have been working in the same line of business they will lead- more team leaders, than managers, and inclined to manage only what they personally understand at the operational level (and could personally do if needed).

Not really a good recipe for "scalability".

It is an issue that in Italy I saw in most of my cultural and organizational change activities, and usually the solution was actually... a choice by the top management/owners to take a risk.

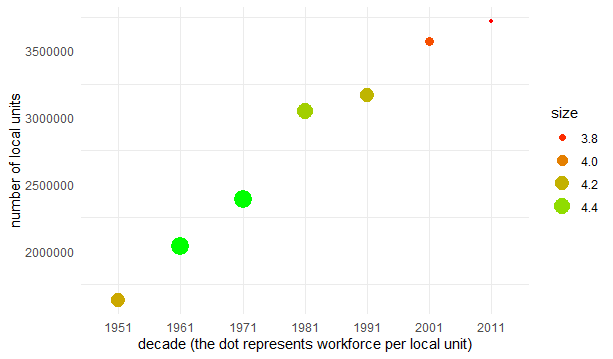

What do the data say?

As you can see, during the "economic boom" we had a slight inclination to grow local units, but while the number of local units grew in geometric progression, currently we are at the smallest end of the scale (I am curious to see the next data update).

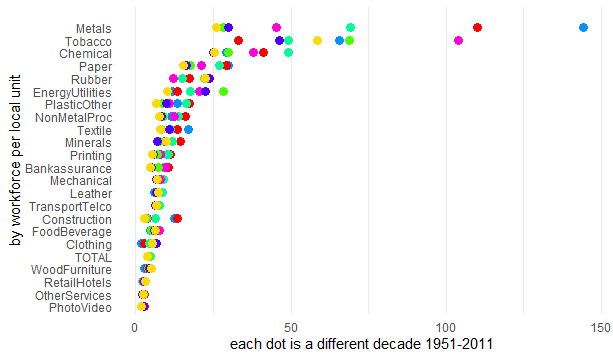

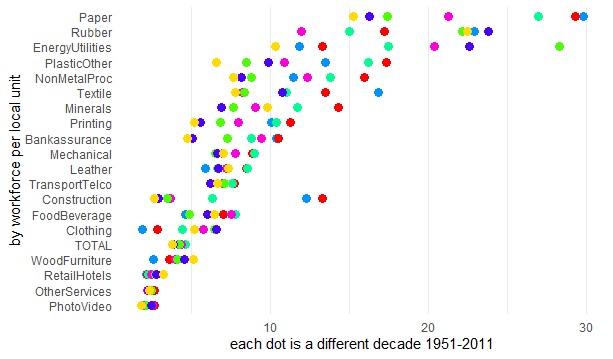

Yes, we have few large companies, and those actually are "outliers", as some industries by the nature of their processes require large size:

But if we remove the "outliers", the picture is clearer

As for the colors in the two pictures above: different colors are different years

| 1951 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 2001 | 2011 |

| lightblue | red | green | magent | lightgreen | blue | yellow |

For example, look at the textile, printing, bankassurance, construction industries: local units in 2011 were at their smaller workforce size since the 1950s.

This is in part due to the increasing trend since the 1990s in Italy toward various forms of subcontracting and "splitting" activities- and this is partially unfortunately taking its toll on the security side.

At the same time, as I lived and worked in few countries around Europe, I am used to commute- sometimes even 1.5 hours each way wasn't unknown (e.g. in Paris), even for white collar.

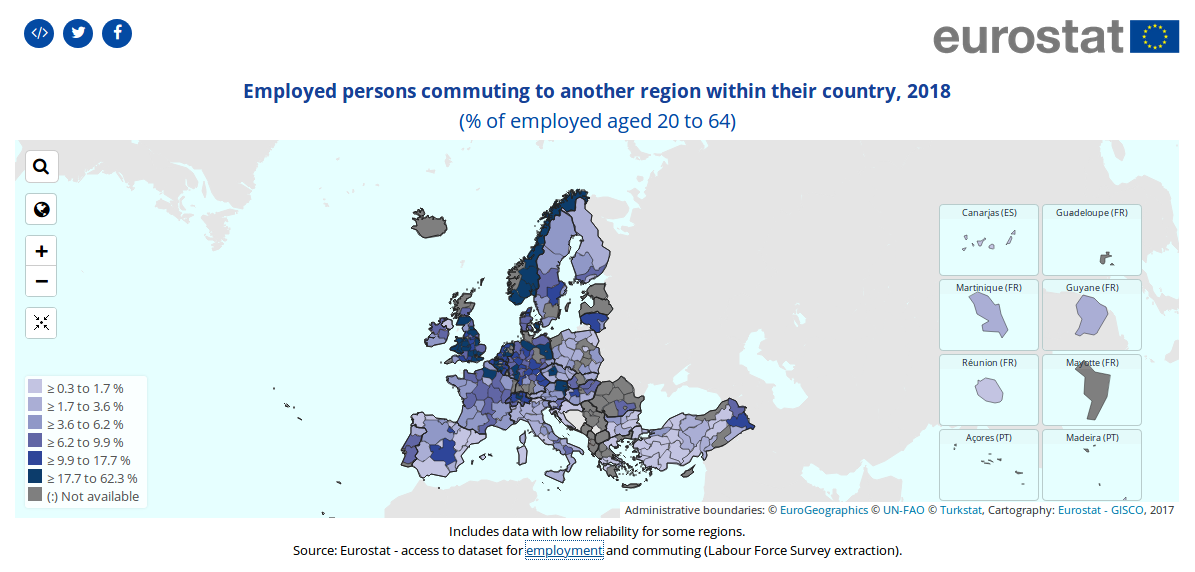

If you look at this picture, you can see how commuting is more developed in other countries that in Italy. (the source can be found here)

(the source can be found here)

On a personal level, commuting is obviously a pain.

But on a social and business level, it implies that human capital can develop through "attraction points"- e.g. while studying in or visiting Frankfurt, I saw how many people were shuttling from "nearby" (in high-speed train times) towns, to work in a company in a specific industry, knowing that if needed they would switch company in the same industry.

This enables to have, say, towns were human capital has a chance to switch employer, develop new skills, and maybe switch again- but, as it is a shared point, it actually generates a local market and "knowledge capital chain" that would be simply not possible is, say, people 20km away were never to move away from their own village.

At the same time, if you have an "attraction point", that could also create competition and therefore attract customers from other industries, which, in turn, could create other attraction points using the services of the main attraction point.

In the XX century, this required physical proximity; in the XXI century, just knowing that there is a "pool" of expert service providers in point A might make interesting from a pool of customers in the same industry from point B to "connect", i.e. become customers ("being there" is not anymore a matter of being physically there).

If the future will deliver shorter working weeks and working hours, or anyway different "working modules" (e.g. 2 days equivalent in office, 2 remote, 1 just with remote meetings from a shared telepresence facility, spread across the whole week), probably there will be less "peak travel".

Anyway, as I wrote in the article that I linked above:

"Over 25 years ago, the CEO of a customer highlighted the need to change not just how things were done, but also the mindset in his company- an interesting change management mission.

An issue that across few decades saw often in Italy: way too often there is not enough focus on the benefits to the overall organization (which mirrors out lack of sense of ownership of the State).

We are partitioned in thousands of tribes, actually parochial tribes.

Few adopt a multi-disciplinary approach- out of fear.

Fear to get involved in activities that nominally would deliver benefits to the company, but, being outside their own scope, would become for themselves a liability, a constant drain of time and resources for no personal benefit."

Thinking systemically is what often is discussed, and in Italy right now it seems that every conference or workshop I attend in person or remotely has a bit of that "trendy concept".

As I wrote back then, you need a mandate from the top (I turned down cultural/organizational activities were there was no commitment at the appropriate level), and you need also to have disincentives for behavior that lets issues turn into problems just out of neglect.

All those elements anyway require, either within the company or within the society at large, a background that develops human capital able to blend what is available to deliver what hasn't yet been delivered before.

If instead what you create is just human capital able to manage only what they could do themselves, you ensure continuity- but destroy any potential of innovation, and unless you have a unique product or service with no alternative, you are digging your own business grave, maybe even while doing investments that are misaligned with your business needs, just because there are incentives.

Look around you: from medicine, to mobile phones, to transportation- fifty years ago most of what now is your everyday reality did not even exist.

Over the next few decades, I do not know if we will end up really living as in "Blade Runner" or as in that MIT study on the future of cars and mobility, published in 2010 (also to celebrate 20 years since Womack's "The Machine that Changed the World").

But one thing I know, and I shared this morning on Linkedin:

"An #industrial #policy isn't just about #manufacturing or the #knowledge #supply #chain - it is about #people, #infrastructure, and other enablers

Including revising society choices on living and working

While designing a new industrial policy for a future expanded urban society and its mobility needs, it is worth considering in data what, despite the discussions and perception, is current reality

Cultural change might start with an idea- but cannot avoid an assessment of reality on the ground

Hence, visiting this interactive map of the EU could actually help in focusing

As you can see (notably for us Italians, used to "import" processes from abroad)... one size does not fit all..."

_

_