Viewed 5041 times | words: 6345

Published on 2019-11-26 | Updated on 2019-11-27 06:11:21 | words: 6345

Innovation. Sustainability. Clean energy. More sustainability. Inter-generational contract. Even more sustainability. Increased urbanization. Further more sustainability...

... you catch the drift: routinely, we got used to buzzwords- at least, this is what I saw since I started working officially in 1986.

If there is a buzzword, you are "trendy" if you pepper your speeches with it.

Even better, if the buzzword is actually something that can cover old and new practices.

Specifically, everybody now, in business and politics, talks about sustainability- and, often, use this new cover to "revamp" old initiatives.

My rationale? As I discussed recently (and wrote both recently and long ago), I think (and I am supported from data) that Italy isn't just still suffering the side-effects of the 2008 financial crisis.

The 2008 crisis was just piling up on an already weakened socio-economic fabric that, while extolling the virtues of anything from our Ancient Rome Empire (I am not joking) to the 1950s-1960s post-WWII "Economic Boom", in reality had been retrenching already in 1986 (in Italy, I used as a litmus test across the decades what was inside working contracts, as there is a concept of national contract by industry, called CCNL, that, first as an employee, then as a management consultant, had to deal with more or less once a decade- most recently, just by attending since 2012 various conferences or workshops updating on labour law).

In this post I will leave aside discussions on industry-specific issues (e.g. automotive, banking, retail, logistics, etc in Italy), but will try to summarize ideas I shared with others and in previous articles, adding references to both data and recent interesting speeches and articles in Italy.

Industry-specific posts will appear over the next few weeks on the Rethinking Business section of my website.

So, what is sustainability? A buzzword?

Introduction: buzzwording your way to the future

You probably heard of the 17 "Sustainability Development Goals" (henceforth SDGs), that in 2015 followed the prior 8 "Millennium Goals".

Of course, you can find more details on both United Nations sites.

There are also (free) courses online that, in few hours (or less- depends how fast you can hear English) can deliver both an overview of all the goals, as well as real-life examples of how SDGs are actually influencing (or have been embedded within) the strategy of multinational corporations (e.g. I followed few courses on sustainability and, directly and indirectly, SDGs, on open.sap.com, involving both SAP, multinational companies, non-profits, and advocacy organizations, e.g. on a different approach to financial reporting that integrates also sustainability and social responsability items, Integrated reporting).

Another bit of multinational guidelines that I already used in the past, when asked over a decade ago by a customer to propose a corporate governance framework based on Sarbanes Oxley Act of 2002, was the Guidelines for multinational enterprises, which is routinely updated and whose signatories include not just the 36 OECD countries (a.k.a. "rich countries club"), but also 12 others countries, as of 2017.

Incidentally: the "OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct" is available online, if you are curious and in (public or private) business.

If you are within the finance or banking business, see here.

No, this short introduction isn't to share what I did long ago or what I (re)learned recently (also because, while I studied the principles over a decade ago, I re-read the "guidelines" only when I have a specific business for customers that, directly or indirectly, could benefit from it- no point in re-inventing a wheel, whenever there is already a "common lingo").

My purpose is more limited: it is to show how, while doing ordinary business activities, you can embed concepts about sustainability (that isn't just about the ecological environment) without adding costs: it is often a matter of doing things in a different way, not of layering sustainability on top of your existing business, as some seems to do.

Actually, as I wrote in the past, the latter is the routine approach adopted whenever "new standards" are introduced, e.g. in the early 1990s, at least in Italy, ISO9000 and its quality requirements were an additional cost, before companies started moving the ISO9000 preparedness upstream- but, to many, it seemed easier to absorb an additional cost, than doing what also ISO9000 implied, i.e. rethinking your business.

This short introduction is also to politely hint at something else: in conferences and on the media, often SDGs are presented as if they were something of interest for developing countries.

A significant distortion: the model represented by the SDGs really is worth looking at also in our developed countries- it is a matter of global convergence toward a social and governance model, like it or not.

The paradox is that those working on SDGs, including national statistical bureaux and multinational corporations, know fairly well that SDGs apply to both countries and companies: it is only the media and general (and, unfortunately, most of the business) public that seem to consider SDGs as a kind of "feel good initiative".

Currently, I am based within the European Union, specifically Italy.

Therefore, while preparing for a way to re-use my cross-industry experience (have a look at robertolofaro.com/cv, or my linkedin.com profile, if curious), as part of my knowledge refresh I am doing EU-focused data-projects, to support my publications on change, and "fix concepts".

The first "week-end project" was released last week, and was on reusing concepts and technologies I developed and used before to turn a dataset containing ECB speeches since 1997 into something easier to search by association through a tag cloud (you can find it here; the original dataset from ECB was updated up to 2019-10-25, I expanded to 2019-11-22 before processing it for my purposes, and will keep it up-to-date at least monthly).

I will eventually add other "features" if and when will be needed for my publication activities (as you can see, I do not even use advertsiment)- but if you see something that would like to be added, just contact me on Linkedin (incidentally: on the website you will find also a link to where you can find the database with keyword frequencies that I shared on Kaggle, if you have your own search project that might benefit from that; and yes, also my derivative work is under a form of Creative Commons licensing that requires just to transfer the data "as is" and attribute the sources, before doing whatever you want with it).

The next project (probably in the first week-end of December 2019, I try to have a week-end project a month, but might accelerate if needed) will be actually on SDGs.

Forthcoming projects? On various EU-, Italy-, and industry-related themes.

Changing social structures

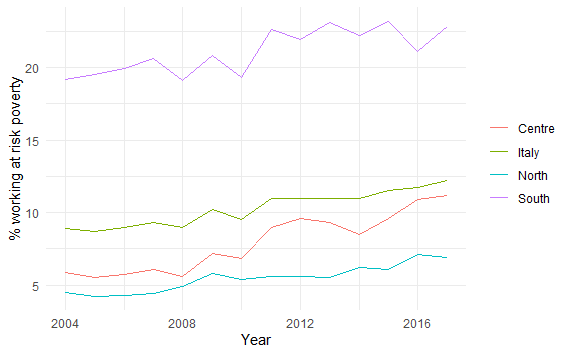

This first chart is based on data provided by the Italian national statistics agency, ISTAT, and referencing a SDG that many wrongly associate only with developing countries, specifically an indicator within:

| Goal 1 - End poverty in all its forms everywhere / Porre fine ad ogni forma di povertà nel mondo |

Before moving on with the article, I would like to be more specific: SDGs aren't just 17 goals, as overall there are more than 100 indicators associated with the SDGs (you cannot have a goal without KPIs to chart your progress).

Look at this picture:

Technical description: "1.1.1. the share of employed people aged 18 years or over at risk of income poverty (with an equivalised disposable income below the risk-of-poverty threshold - This is set at 60 % of the national median equivalised disposable income after social transfers)".

In plain English: the picture is about an indicator that affected all the "rich countries" since 2008 (but, as I keep repeating, affected Italy well before that- I saw a crisis looming already in the early 2000s): the decline of the middle class.

Beware of the difference between statistical, reported truth, and "informal" economy, whenever looking at statistics, as there are different ways of being "informal" across the country: what really matters is the country-wide trend.

In the 1940s, after WWII, Italy became a republic. A new republic, with a Constitution that was redefining the role of citizens and State.

Our social structure was not to be static, as it wasn't just about rebuilding the country after a war, the lofty aim of the new Italian Constitution was to create a new "social contract".

If compared with the previous social structure, a "pyramid" was as close as it got to importing in Italy the "American dream".

Indeed, during the "Boom" post-WWII, fortunes were created, and Italy became more urbanized than before, built in few years XX century infrastructure, and the sky seemed the limit.

Just look at how long it took to build in the 1950s the "Autostrada del Sole", linking North to South: less than a decade, i.e. more or less as long as... it took over the last decade to renovate the interiors of few Metro stations in Rome.

Also because... let's say that rebuilding the nation trumped over minutiae such as working conditions, protecting the environment, long-term sustainability, etc.: we started footing the bill for the various "cutting the corners" few decades ago.

I wrote in previous articles about what happened since then, e.g. have a look at the article that I posted on November 10, 2019.

Fast forward from the 1950s 60 years into the future.

When I re-registered in Italy in 2012, one of my first tasks was to "get up to speed" on what had happened in society and politics while I was living abroad- on the ground level, not just at the macro-level.

As I wrote above, I worked in few industries, in Italy and abroad (albeit in automotive almost exclusively in Italy), so it was just natural to start on a path to see what had been reported on books vs. what I had learned via experience first, and then fixed with books, until the late 1990s.

If you had access to my library loans and book purchases, you would see how many books about Italy, Italian banking, and the FIAT/FCA/whatever group I went through.

Actually, my librarything.com/catalog/aleph123 profile is a good approximation of what I read or I am still reading (e.g. look at the categories Italy and Europe or Nextpolitics).

Some of the books were a waste of time (conspirary theories or instant books on temporary political celebrities are a classic staple of Italian bookstores), others were "OK but nothing more than cross-checking", and, for the few who were at least 3.5* out of 5*, I posted the review both on LibraryThing and on my own website, under the Selective Bibliography section.

I was relatively selective also in choosing which books to read- so, ended up having 99 books that I assumed could have material worth thinking and sharing my impressions about (not only about Italy).

Beware: "worth thinking about" does not imply that I agree with the author- in learning, innovation, politics, I think that reading only what confirms what you already agree with is a dangerous form of "tunnel vision", a type of bias that is actually one of the weakest elements that I find in both social networks such as Facebook, search engines such as Google, and other media.

In Italy, whenever somebody is in power and seems steadily in power, frankly our mass media suffer from an intrinsic "courtesan syndrome": as if they were to fear to be left behind if they weren't extolling praise on those suddenly identified as newsworthy.

Now, imagine what that means in country were we had over 50 governments in 60 years...

If you are interested in biases, have a look at a post with bibliographical links that I shared on Facebook (book and article links are within the comments- beware: they are "technical", i.e. social scientists number crunching, but useful also if you skip the more "technical" part and look just at the intro, tables, pictures).

Along with other books, a picture that I found interesting was within the most unusual of sources: a book on automotive marketing, published few years before 2012.

Italians are (or should I say used to be) compulsive drivers.

I like walking- but in most places, also due to some quixotic arrangements within public transport and traditional unreliability of schedules, Italians post-WWII got used to identify with their car.

So, instead of walking few minutes for 400 meters, they prefer to get the car, spend 5-10 minutes between traffic lights (those respecting them, I mean), another 5-10 minutes to find a parking place as close as possible to the destination and... all the way back.

Therefore, I remember how car ownership was linked to career paths- I know, my USA friends would be surprised, as it is similar to what they told me, but in Italy it wasn't too far from their habits.

And, of all places, even more so in Turin, as it used to be a company town.

Therefore, the idea was that getting through the "social pyramid" implied having a car that matched your status.

In that book, the late 2000s (post-2008 crisis, and I will not repeat what I wrote above about the Italian side of the crisis) had a different market, getting closer to the hourglass model:

The implications outlined within the book? Those on the bottom half of the automotive market extended the life of their car, while those above shortened it, changing cars more often (due also to some tax side-effects that would impact mainly on companies and those with a higher personal income).

The point was: in the previous structure of the market, the idea was that you could move from one "layer" to another.

The increase of the share of working people who could slide into poverty was actually matched since the early 2000s by a restructuring of consumption patterns from others that, in the past, used to be considered in Italy middle-class, i.e. aspiring to be closer to the top of the pyramid (it wasn't just a matter of cars- also of where and how often you went on vacation), while actually being confined, at best, within the top of the bottom half of the hourglass.

Recent laws (over the last, say, handful of governments) tried to reverse another, associated pattern: a contraction of long-term employment and an expansion of the "gig economy" also to activities that required anyway continuous presence and a long "phasing in" learning pattern.

Now, imagine seeing gradually jobs whose "learning curve" required (not out of necessity, but out of organizational habit) a 3-to-5 years learning phase suddenly being staffed with people who worked on 3, 4, 6 months "temporary contracts".

Eventually, both sides adapt, and, beside losing the concept of "career progression", also business processes turn toward surface-level depth of experience, and tuning processes accordingly.

The first thing to go? Organizational memory (and I wrote about this issue also in the early 2000s- have a look at the 2013 reprint BFM2013).

Concept: social structures are both a cause and a consequence.

The consequences of compressing learning cycles

Techno-enthusiasts usually expect as a future social structure something completely different.

A model where there is a minimal base of service-oriented employees covering what cannot be automated (e.g. services to individuals, part of the welfare and health system), while retaining a degree of "meritocracy", and spreading resources vertically across the social structure.

The most optimist between those techno-enthusiasts are actually almost talking of an upside-down pyramid, a new "Golden Age" brought by technology.

The loss of organizational memory? Not an issue, as (so they say) "machine learning" will be able to continuously recover what the company knew, and maybe eventually it will be software coaching new employees.

There is a fly within the ointment: I am afraid that what machine learning finds, at least in most application I saw, is at best what was done.

Organizational memory is about "why", not just "how".

"Why" was chosen that pattern instead of another one?

"Why" the process was then organized that way?

"Why" was selected that technology and that people with that educational background?

"Why" it was assumed that it would be enough that also for the future?

And so on, and so forth.

In most organizational decisions, obviously there are competing factors influencing choices: from budgets, to availability of resources (human and technical), to contextual factors.

"Stakeholders" is considered often to mean "humans to be convinced not to turn into roadblocks".

Personally, I think that actually stakeholders could be a form of "crowdsourcing long-term sustainability": but I wrote plenty of articles in the past about changing social roles, e.g. customers embedded within innovation and marketing cycles, and I think that you can find plenty of examples around you.

But what about laws? And what about (business, social, corporate) political opportunities that tilted the balance toward that choice while another one was equally sound?

If you lose contextual perspective, you lose the ability to innovate- as at most you are able to do incremental innovation (what some of the proposed options of machine learning could do), but not disruptive innovations require not just being "new", but also being "sustainable".

In some cases, I already saw many "innovative business models" presented by some e-startups being "new" only because... those presenting them (and, unfortunately, those provided the funding) had neither social nor organizational memory.

Sometimes, many modern futurists and techno-enthusiasts sound as Schumpeter "in sedicesimo": less reading, less learning, but plenty of quotable one-liners.

Ideal for memes, but a business plan isn't made by memes, it requires a convergence of factors and resources (and a decent understanding of what is the context).

And its implementation requires also the ability to toss it in the bin if you see that its "groundwork" lost its alignment with reality.

Concept: any choice derives from a context- remember "why and why not", not just "how".

Thinking globally, acting locally

It is nice to talk about "urbanization" as if it were a case of "one size fits all".

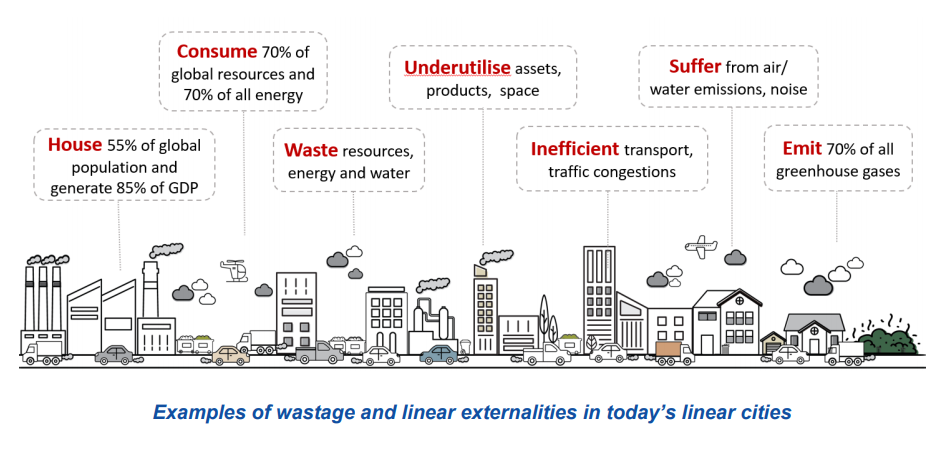

I like this picture, relaunched from the WEF (but derived from an European Investment Bank report)

No, I do not agree with the article from WEF- as I have a social model in mind that is not derived from the Club of Rome approach.

Anyway, I shared in the link within the previous paragraph also the original article, just in case you are curious (the title of the WEF article was... "Everything you need to know about ecological economics"- well, Club of Rome level of prescriptiveness).

There are many dimensions of urban development, and "smart city" is yet another trendy concept, that has specific implications on sustainability: not just for what it delivers, but also for what are social conditions needed to make a smartcity thriving.

As I keep discussing locally, the shift from the (potential) pyramid to the hourglass social model has a side-effect, if you increase educational level (as required also by our benchmarking with our European Union partners, also if many forgot why there was that request): you create large clusters of developed but never applied skills.

Already almost a decade ago, while talking with my Italian contacts, I heard way too often "I did an exam on that", as if learning where to be a "checklist" affair.

Akin to "things to do before you turn 30".

Some local commentators recently said that the number of top roles has not changed, so there isn't that much need for all those university graduates.

Well, those saying so obviously were already "in", and forgot something: while 1950s consumer and business technology used e.g. by ordinary office workers required basically just to be able to read and little more, look at all the concepts that, embedded through day-by-day learning of patterns, are required to be able to use e.g. a personal computer, a smartphone, or even just a tablet.

Increasing educational level wasn't something added as a goal just to be "trendy"- but because, in a complex society, the degrees of freedom (in terms of what you can do without affecting others and maybe even the system) are reduced, if compared with a self-contained pre-industrial village economy.

I know that I keep repeating it, but it is worth repeating until somebody listens... we are compressing the decision-making cycles, while increasing the complexity of interactions.

So, if anything, we need to acquire earlier skills and problem-solving (or, at least, "connecting the dots") abilities that in the past were of interest only of few "experts".

Again, it is akin to reading and writing: centuries ago, weren't compulsory social skills- today, it might well be true that many are losing the ability to write, but living in our society without the ability to read and understand constant streams of ever-changing information is already creating issues to our democracies.

I disagree with those pushing for regulations for the Internet, social networks, etc. just to "save our society from fake news".

What will save our society from fake news is the development of critical abilities to understand when news are distorted- I remember as a kid reading an Italian book on... "how to read newspapers" (Paolo Murialdi "Come si legge un giornale", 1975), and one of the funnier elements was... decoding "newspeak", e.g. how news about military retreats could be reported.

In other countries, high school students learn how to fill the annual tax return, and I remember how we were used to read and discuss bits of the Italian Constitution.

I know that there are those that, without even understanding that they are actually following the same pattern discussed by nazis for Ukraine in WWII, advocate "dumbing down" to make easier social control in a society that lost the "American dream", but that is a self-defeating endeavour.

Each country should adapt to its own future, not just adopt recipes developed elsewhere.

Italy has a critical issue: we have limited natural resources- and, therefore, as a "transformation" country, either we generate value added in our transformations, or we have to fight on cost.

And fighting on cost, while everybody else is increasing the investment in, say, research and development, infrastructure, education, implies that you assume that you have a level of efficiency that no amount of automation or intellectual property or human capital development can defeat.

Frankly, a little bit arrogant and outlandish, as a perspective.

Let's say that, as I hear often, we Italians want to become "the" destination of choice to develop new ideas, for high-spending tourists, and to use our flexibility built around small companies to develop a new form of competitive advantage, based upon what is "uniquely Italian".

For few minutes, assume that this could be possible and is feasible.

Now, what would be needed to make that possible?

Concept: develop a local mix that makes sense locally and is competitive globally

The alchemy of competition, Italian version

Recently, I attended few conferences and events in Turin, and of course read more books and articles about Italy and its economy.

I am boring: but I think that, if you have a country were most companies have a smaller and smaller operational unit size, you fail to develop (or lose, if you ever had) the ability to manage and coordinate and govern (three different concepts) complex processes.

Not too long ago followed a course on "scalability", as a refresher of something that I studied between the late 1980s and mid-1990s while working for customers where I needed to understand what implies "scalability" on the operational side.

It is not just a matter of adding more people or dumping money: if you are used to have three-person teams, you can end up as I heard often in Italy also from colleagues.

Up to 50 people in consulting, and few hundreds in other types of "commodity" services or manufacturing, you are really managing an extended family.

If over 90% of the Italian companies are small (and their operational units are even smaller), few have the time and resources to allocate to develop what everybody in almost every conference or workshop I attended in Italy since 2012 kept repeating: managerial resources.

In a recent conference, it was interesting to hear from a large company (Leonardo) that doesn't deliver mass-consumer products (aerospace produce are moving fast in some cases, but cannot really be calles Fast-Moving Consumer Goods, FMCGs) of two sides of the Italian coin.

A company producing highly complex products but in relatively small quantities and with a long product lifecycle has out of necessity (at least for now- intelligent automation will change that, eventually) a large number of small suppliers, suppliers that can survive with small quantities spread across time.

Side A, we are competitive- our salaries are lower, also for specialist jobs with long-training cycles, such as aerospace engineering, and most Italians, as I showed last week, aren't as mobile as our fellow Europeans (to say nothing about my American friends).

Side B, our companies are too small- and this creates some issues whenever Leonardo itself has to be part of larger projects, or probably also mix-and-match tiny local companies with major suppliers of subsystems.

The solution adopted by Leonardo is something I observed also in my contacts and visits around Italy: the large, more structured, more "multinational" company has to help smaller suppliers to "grow up", by de facto developing its own version of a MBA, but tailored to small companies.

Smaller companies have neither the structure nor the human capital to absorb complex processes- and also when meeting smaller companies I saw the cultural difference between those who were embedded within the supply chain of larger, multinational, or just more structured foreign companies, vs. those who were maybe successful, but because were competing on price, and therefore temporarily useful.

For the latter, you just need to "buffer" to avoid that their inefficiencies or inability to manage timelines, synchronization, etc generate ripple effects on the whole supply chain.

I like to remember to my Italian contacts that sometimes are inclined to see the country as a lost cause that, in reality, even recently a foreign company purchased an Italian supplier stating a simple truth: they liked their Italian supplier, liked their products, but had just paid a penalty to a major customer due to delays resulting from inefficiencies and mismanagement downstream- so, they purchased the company, and said that the reason that they did so was to provide what the Italian company lacked, i.e. management.

Some locals in Turin joke that I keep repeating that the model that some would like to implement in Turin (and Italy) is idiocy and wasting our acculumated human capital and competitive advantage.

So, I will keep repeating it.

My idea is simple: just because our ruling class is living off the proceeds of what at best was developed in the 1950s-1960s, i.e. converting into "rentiers" and turning assets into disposable income or financial investments, and for fear of losing control would like to "dumb down" the country, it doesn't imply that that is a crystal case of "leadership".

In my view, their proposal is glorified self-defeatism, and I criticize it even more when it is coming from my political side (centre-left).

In my view, it is a pipedream to think that you can turn the country into a giant version of Disneyland, and have all be happy and rich: it would just turn at best Italy into the "maquilladora" of Europe, and a giant amusement park, where most of the local population would work in low-value-added services.

Or: a recipe for a society where local will be able to cope with superficial complexity, but unable to either govern or develop the benefits that our XXI century social, economical, and, yes, cultural development could deliver.

Look at our national health system: how long will it stay sustainable, if the tax base will shrink or become "poorer"?

It would make more sense to say that our centuries old universities and associated local knowledge supply chain are a resource for the XXI century, a resource that has to be maintained and developed, and the latter is possible only if it caters not just for the locals, but for a larger audience.

Food, wine, etc? Well, do not forget that until few years ago we were also proud of our luxury fashion.

And, instead, recently, I was reminded that the aggregate turnover of the Italian luxury industry is smaller than the one of the top four French companies (companies that, incidently, went shopping in Italy).

So, food and wine and hotels might be an asset- but a complementary asset, as developing a service industry able to attract top spenders requires a different level of service personnel, with a different culture.

If you were to blend the overall "quality of life", "quality of educational system", and flexibility embedded in our small companies (after developing their ability to work with companies from "ordinary countries"), that could actually deliver an ability to compete.

Yes, Italy lost the train of big multinationals- so, maybe, it makes sense to consider what would make our companies and country attractive for both using and developing our educational system (e.g. already in Turin there are universities collaborating with foreign companies with a local, structural presence).

The model that I hear locally instead is, in the end, competing on our unique food, wine, past culture- but without doing the investments needed to keep that advantage in the future: already we lost our primacy in luxury consumer goods mainly through arrogance and inability to "scale up", do we want to continue?

Concept: do not assume that your competitive advantage today will last forever

Conclusions

As I shared alread online few days ago...

... I have just few doubts on #national and #local challenges in #Italy and how well we are coping with them...

... before somebody sets up yet another commission to create yet another industry policy and associated "strapuntini" (i.e. new coordination agencies) to churn out Powerpoint presentations.

As I said earlier this week to friends in different ways... in Italy, with have too many who play the psychologist, investigator- and overall HR coach, but few act as managers and negotiators.

A country of facilitators cannot work- as, in the end, you need to converge all that facilitation with the allocation of scarce resources.

Personally: I think that Italy and specifically Turin are at an interesting crosspath, using the "concepts" above to summarize:

- social structures are both a cause and a consequence

- any choice derives from a context- remember "why and why not", not just "how"

- develop a local mix that makes sense locally and is competitive globally

- do not assume that your competitive advantage today will last forever

It is a Cheshire cat issue: if you do know where you want to go, any direction is fine.

XXI century corollary: but you may well waste all the available resources trying to fix fire after fire before you get to the source of fire.

Let's, as an example, summarize the local (business and non-business) sides:

- the main local industry in my birthplace, Turin, mobility/automotive, needs to undergo a significant cultural and organizational change- not just FCA/PSA (due to the M&A), but by consequence also Renault (where managers are being extracted toward PSA due to a management transition that wasn't), Nissan, and Iveco plus Comau; it might as well impact the local R&D/corporate presence units of GM and Bosch

- I apologize with Bibop, but also if Hyperloop weren't to go live, developing R&D locally to integrate systemically into a product and service the technologies involved (most of them already available) would, anyway, significantly improve Turin's "systemic thinking" culture and get closer its aim to become an open-air urban-area-wide "living R&D" on the industrial, technological, social, business impacts of new forms of urban development and mobility

- accordingly, also local authorities (in Turin, there is a structural overlap between town, Metropolitan Area, and main area of the Region of Piedmont) will have to develop new governance and cooperation concepts, escaping the old habit of dumping grants and finance to support private attempts at developing something new- and turning into enablers and "proactive watchdogs" of a different public-private-partnership model

- accordingly, this would imply rethinking some "dumbing down" proposals from part of the elites- we need more brains available and involved in different ways, if we really want the urban area to turn into "showcase of a possible future", as all those involved (i.e. also those just living) should be able to contribute their suggestions and proposals- probably with a swarm filter, not the usual top-down

At the national level,

- everybody and their dog (or cat, if you are cat people) can see that our multi-level "half-baked national subsidiarity" (look on wikipedia what in EU means subsidiarity) isn't working

- we need a new, smarter subsidiarity- extending both vertically and horizontally (e.g. sometimes local stakeholders have better information "from the ground" and continuous experience on how to make something work efficiently than local or national authorities doing it once in a while)

- despite all the pretense otherwise, it still is "cuius regio, eius religio": i.e. quit the hypocrisy in way too many speeches on the role of private companies and public authorities- yes, long-term sustainability is in the interest of both, but, meanwhile, the former look at the next quarter, the latter at the next electoral cycle; harmonizing interests (making them compatible) instead of doing a routine sing-along of "somewhere over the rainbow" pretending to be all marching at the same tune is mere coping with reality

- sometimes Italian politicians and businessmen talk as if they were lifting quotes from the "Leviathan"- all parts of the same body, etc... but actions conflict with their wording: so, maybe, it is the right time to have a frank discussion on which industrial and development policy we want to have

- mumbling over a future will not deliver one: you cannot have a policy of growth that meanwhile contracts GDP, cuts national debt, releases resources for investments to restructure our infrastructure to cope with forthcoming natural and social challenges, and, at the same time, maintains our welfare and educational and health system- it is a matter of choices and priorities across time

So, until the next article.

_

_