Viewed 9991 times | words: 6839

Published on 2023-11-09 23:30:00 | words: 6839

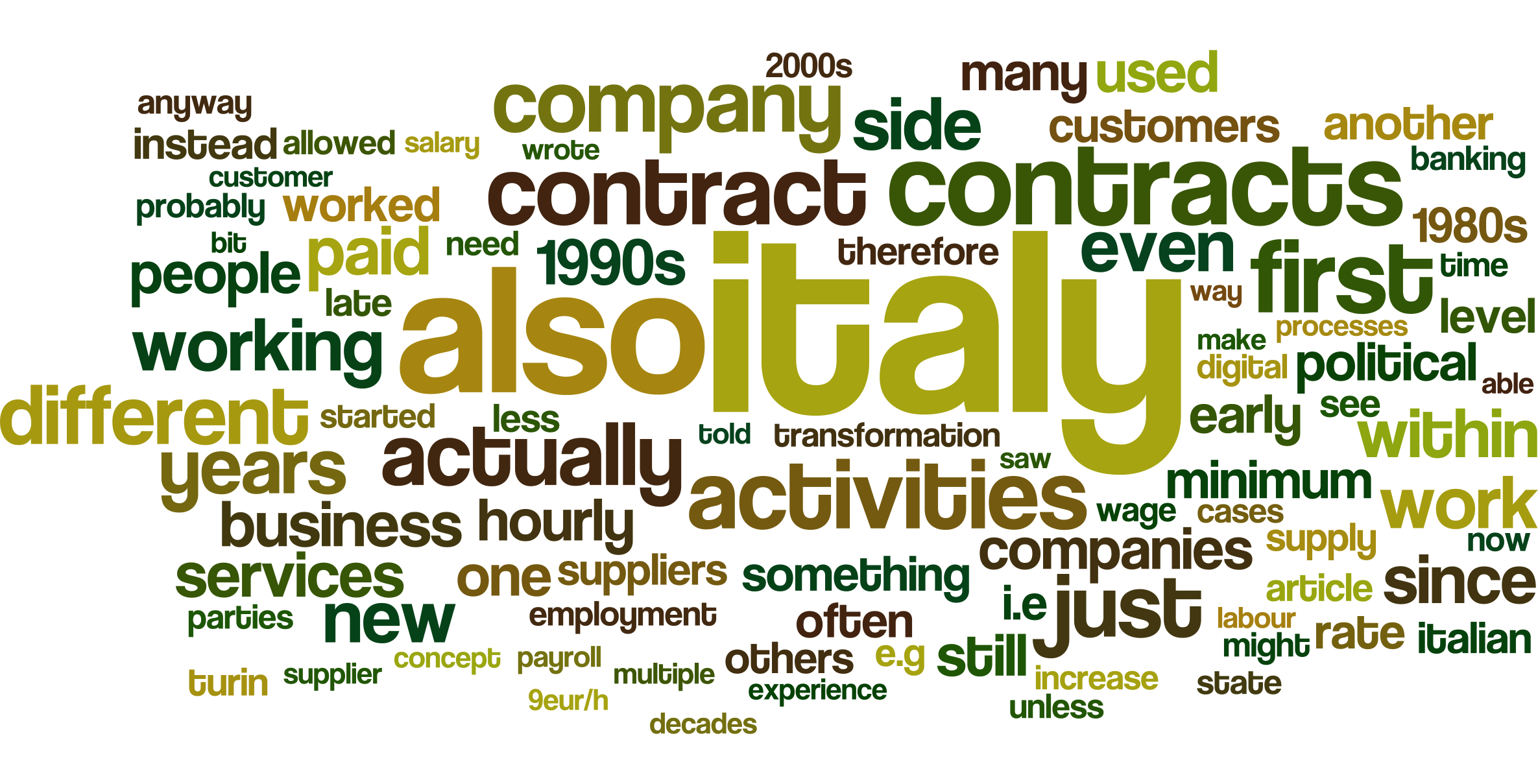

This article is about what make our 24/7 economy work: people.

Anyway, I blend people and my data-centric side, as I did since the 1980s, as I think that what many heralded as the "work of the future" has already, courtesy of the 2020-2021 COVID pandemic, been tested across all the business domains.

This "test" allowed to actually carry out formal and informal assessments on how our "ordinary" way of working had not evolved as much as we believed, notably in terms of enhancing the positives.

This article is mainly about Italy, but with observations also about Europe, as I worked in few countries (and, also while in Italy, with people who were based in few countries, both in Europe and elsewhere).

Also, in the last section, to discuss the mindset shift needed, with reference what used to be the main industry of my birthplace, Turin, i.e. automotive and related.

Therefore, consider it as a kind of "sharing draft concepts on the human side of supply chains", looking at today to think about tomorrow.

It might well be that in the future will published another book on the line of my old e-zine on change (2003-2005, updated reprint of 2013), the book on talent management, or others.

For now, few sections in this article:

_ contracts and working life in Italy

_ the impact of digital transformation Italian-style

_ the Far West of contracts and minimum wage

_ it takes more than a village

Contracts and working life in Italy

I started formally to work in Italy in 1986, but actually had looked for short employment and "gigs" also while in high school, from 1979 until 1984.

Eventually in the early 1980s first worked part-time during a tech exhibition, selling home computers and videogames, and then after the end of high school selling also used books, while earlier had done some "ghostwriting" for essays.

And, of course, had also a chance to have interviews for jobs whose contract was nothing you would sign.

For my first real job, after serving in the Army, had first a short training contract, where we were paid a fixed daily expenses reimbursement during the training (held in Milan, on COBOL mainframe analysis and development) and, for those who passed, were confirmed the entry salary that we were told about during interviews- approximately 600EUR/month net in 1986.

At the time, those with an high school leaving certificate were hired as "impiegati di concetto" (desk-bound employees), with a specific form of contract that included a clause that after two years of "on-the-job training" you would shift from one level to another (in my case, the software company adopted a manufacturing contract, so we started with the 5th level, the first level for office workers, and would then get 5S).

I am one of those boring people who, when given a contract, unless there is no choice but signing (the legal concept is "obtorto collo", the movie version is "an offer that you cannot refuse"), would rather spend some time reading it before signing it.

For business reasons, beside reading the contract(s) applicable to my own employment, also for customers and partners over the years had to ready and study different contracts for different industries.

Therefore, I can say that saw the evolution in the 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, 2010s, and 2020s- both for myself, my customers, and, often, asked by others to have a look at their own employment or consulting/freelance contracts, and to explain clauses and their consequences.

As most of my activities since the 1980s have been about communication and not just about technology or business, I actually find a bit conservative to describe this as "evolution".

When I first moved abroad in the late 1990s (to UK), lived in UK but for a while worked first mainly in Paris, and then mainly in Zurich and German Switzerland- there, I did not have an employment contract (had my own company), but routinely had to read or even review contracts for others.

Years later, while I was preparing my return to Italy, accepted to work as part-time Project Manager (and also Business Analyst) for another company that had won projects for State agencies, and accepted also to work at a discounted rate, as it was anyway for the Government of the country I hold a passport of.

It was not unusual: except my first employment role 1986-1990 and then my first role as Senior Project Manager and then cadre to lead a consulting business unit 1990-1992, all that is within my CV (both the "lean" version online and the really long version) actually was a collection of missions where I was called at by former customers and former managers or former colleagues.

Also the missions I got since I had to re-register in Italy in 2012 (as in the early 2000s eventually decided to scuttle the plan to return to Italy and, instead, shifted to Brussels), while nominally through third parties, had been through similar channels.

Both in Italy and abroad, first from the late 1980s was involved in recruitment activities as a "specialist" on a specific domain, but then also to actually interview potential candidates and discuss/negotiate with them salary or rate, after defining the boundaries with the customer or partner.

In many missions, as I wrote above, was also asked by team members to have a look at their employment contracts, after they learned what I had done in the past (including that had been a negotiator on contracts to sell consulting services, software, and to hire staff- eventually also to negotiate severance packages when business relationships were phased out)

Hence, I had a chance to study more than once the evolution of labour contracts in Italy, as I had already done for myself in the 1980s and 1990s, and for customers in the 1990s and 2000s, also after a M&A activity where the issue was that different business units had different industry contracts despite covering a similar portfolio of services.

This is not unusual, in Italy: e.g. in IT consulting I worked both with companies using the "services" contract (that was really designed for retailers) and others using the "manufacturing" contract (that was really designed for manufacturing companies), while I had to view also banking and other contracts (so, ended up also studying the standard national contracts for "cadres" in manufacturing, services, and fossil fuels).

When working with customers and partners, it was also a routine since the early 1990s to observe how many activities had been externalized.

Even the State, for example, externalized processes within the health, pension, tax services that are really components of processes whose knowledge and supervision you would expect to stay within the State-

This "unbundling" is actually something that I saw expand way beyond the expected in Italy over the last 30 years, also if originally made sense.

Imagine that you have a company producing metal widgets: the mindset and work approach used by software developers or canteen cooks or cleaning personnel has nothign to do with the actual product.

Hence, unbundling tried to specialize and optimize, mirroring what was being done with privatizations in Italy.

The first cases I read about in the early 1990s were transferring the payroll and IT (and associated staff and assets) of few manufacturing company into a new company that was jointly owned by a service provider, with contracts e.g. that stated that the first year or first few years the "customer company" would transfer a budget equivalent to what was derived by the application of a mathematical model to the budget prior to unbundling (e.g. average of the last few years, minus non-recurring investments/expenses).

Generally, this was coupled with a further model to reduce the budget by, say, 5% each year, and other clauses to allow the "supplier" to start offering the same services to other companies (including competitors) after X time.

As each labour contract in Italy in the late 1980s to early 1990s had different conditions and "features", those new "suppliers" sometimes selected a contract by analogy of existing companies within the new mission for the new company, sometimes kept the contract of the original company, and sometimes instead quite simply went for the one that allowed more flexibility (and lower costs).

Yes, even in 1986 the applicable national contract (at the time known with the acronym CCNL- Contratto Collettivo Nazionale di Lavoro, plus the name of the industry) was coupled by an additional document that included further conditions and benefits provided by the employer.

Anway, over the years, all that unbundling and restructuring resulted in a maze of contracts: routinely I met people doing exactly the same job but under different contracts, and therefore with different "features".

I remember when a colleague told me in the last 1980s that one of her friends worked as a computer graphic programmer for a company making paint.

Due to the nature of the production processes, she had many more days of vacations than others doing the same work sitting at a desk in front of a computer screen, also if... she never set foot on the factory floor or was even close to paint).

In Italy, most contracts always had a 13th month (paid in December), while the contract used routinely by retailers had a 14th month (paid around July), plus a monthly set-aside to be paid when leaving the company (but eventually was allowed to set that into investment funds).

Decades ago, I remember seeing a strike by banking employees in Turin, stopping public transport, as they protested because they were going to loose... the 15th or 16th month of salary (I do not remember if they had already lost the 16th).

Let's just say that they did not get that much support from citizens waiting for their bus or streetcar, and had at most 13 or 14 months of salary.

To compare, and see how anyway is still complex, you can look at this document from a Trade Union that explains the 2023 monthly salary for banking employees.

Just to stay on my hands-on experience as an employee, if I were to compare what I saw in 1986 when first I had to study an employment contract after being hired, and the latest one that I signed in 2021 for a mission (and the associated reference CCNL), it would seem another planet.

Anyway, most of the projects and missions I worked on in Italy since 1986 included an element of "automation" of existing business patterns, and it is interesting to see how that, too, evolved.

The impact of digital transformation Italian-style

I will skip the first two projects in 1986-1987 (automotive procurement decision support on which suppliers' invoices should be automatically cleared for proposed payment) and 1987-1988 (banking general ledger)- both included an element of automation or extended digitalization of existing activities, but more interesting on that "data-only" side were other projects I wrote about in the past, decision support system models.

My first experience in shifting on the other side of the table, i.e. looking at contracts and payroll information from the employer side, was really in the early 1990s, when my CEO asked me to deliver a study on potential dematerialization of a specific type of records ("libro matricola") for a large retail customer, where my company was implementing a new payroll system.

I replied as I did in other cases where I did not know: "I know nothing about payroll but reading my own payslip", and he told me that I would have worked alongside the payroll consultant that supported the company.

The mandate was to minimize the cost, but do something worth doing and useful to the customer.

It was interesting, to see how also the supposedly archaic Italian State agencies could actually be open to collaboration that confirmed (actually reinforced) compliance but streamlined costs.

And using optical memory in the early 1990s was still a novelty in Italy (and not just in Italy).

So, when somebody asks me how can I claim to have worked on X if I do not have a degree covering that, my reply is always that learned while working with those who had actual experience in that domain.

Working in multiple domains while learning (and being a bookworm helps in digging into documentation) helps also to understand something that I used repeatedly when negotiating contracts for others.

Sometimes you have to get through hundred of pages, to extract a single page that can make things start moving.

Then, in that single page, every single word counts, and every single word is a key to plenty of supporting material (and it is up to you to extract from that pile what is most relevant or supportive of your case).

Jump forward few decades, and, if you are in Italy, look around you, and you will see that many digital transformation initiatives actually added what decades ago I was told in London that in banking in business was described as "sand bagging".

Meaning: you unbundle processes, replace single contact points of reference with either multiple contact points or a single contact point who, in turn, had to do what in Italian is called "giro delle sette chiese" (seven churches tour), i.e. going around to get from each a bit of an answer, and then assemble it.

Then, put as connectors different systems that are not integrated end-to-end to cover the whole process.

And, for good measure, add within the formally fully-digital process multiple points of potential manual intervention, able even to "augment" or modify records, and each check becomes yet another round of endless jumping back-and-forth.

My experience in Italy since 2012 is that this has become a "best practice".

So, you have digital transformation and e-government Italian-style.

It happened with both State, local authorities, and private companies.

In Italy, people get used to anything that is repeated often enough or described as "normal".

Hence, in 1973, the late Giulio Andreotti (7 times President of the Council of Ministers, and almost got an eight round) said that, in order to lower energy consumption, the bulb of each other lamppost would be removed.

Decades later, he was asked within an interview what was the aim- and he simply stated that actually was expensive to do so (just imagine the work required), but it was to give a message to Italians, as otherwise they would not get the point.

The idea of externalizing activities to allow then focused, highly scalable specialized activities is not negative per se: it might actually make more sense than trying to replicate those activities within each organization, where would be used not as often.

Also, externalizing implies that the new "supplier" will probably go beyond just increasing utilization, but also start redesigning the activities to further improve efficiency (say: cost-per-unit-of-service) without affect efficacy (say: level of quality and customer satisfaction).

Doing something for multiple "customers" allows also to build a better resistance to "arm twisting" to bend rules, enhancing the possibility of continuously improve those activities.

The only catch: you should actually retain integration with the other elements that have been externalized, not evolve on different planes of reality- which, in my experience and those reported from others interacting with Italian bureaucracies since 2012, seem to instead a common behavioral pattern.

So much, that few years back, after requests to streamline some compliance processes, it was discovered that the result was to add more paperwork, not less.

I was used since the early 2000s to use the side-effects of e-government in interacting with State bureaucracies, first in UK and then in Belgium.

In both cases, I saw how it was before and after that minimal bit of "digital transformation"- and, in both cases, the idea was to do something to ease access to citizens (private or business) and carry out their own side of the process with greater ease than before.

In Italy, digital transformation instead implied that in the 1990s could file (on paper) a tax return for my VAT registration and carry out all the compliance alone, in 2010s instead would be next to impossible.

So, in 2023, I am trying to see if the new rounds of digital transformation (which involved also streamlining various reporting requirements) will make it easier- if I will still have to stay here in Italy in 2024 and beyond- otherwise, will just have to file once.

The above mentioned unbundling of activities had another side-effect, that will discuss in the next section.

The Far West of contracts and minimum wage

Say that your company in the late 1980s had employees on its payroll covering everything, from the drivers to the reception, to factory operations and maintenance, to even the canteen and factory floor infirmary.

Say that then, in the 1990s, it started externalizing anything that wasn't "core business".

So, if your company is producing widgets, you might decide that reception, canteen, infirmary, and some other associated activities could better provided by suppliers focusing just on each one of those activities- also, would add more flexibility, as you would need to focus on cost and level of service, leaving e.g. capacity planning to your supplier.

Moreover, they would take care of hiring, firing, training, etc.

Also, they in turn might solve e.g. capacity planning by further externalizing.

And, as you can expect, each round of externalization would focus often more on lowering costs and sticking to the formal side of contract, than doing whatever is needed to achieve the result, whatever the cost- as each supplier (or sub-sub-sub-etc contractor) would have less and less flexibility and less and less latitude of activities to balance costs and revenue on.

As I wrote above, those external suppliers might adopt a different type of labour contract, specific to their own industry.

Since I was first resident abroad in the late 1990s, I had the chance of comparing the labour contracts I found elsewhere with those I knew from Italy, and then eventually to update my knowledge on the latter.

If you lived in UK in the early 2000s, you are probably familiar with the concept of "zero-hours" contracts: you get hired, but then you get paid only for the hours you work, but you cannot work for any other company while still an employee (and sometimes even after).

When I first had again contacts in Italy, started seeing that type of contract applied across multiple industries- and not just for manual or entry jobs, also for those roles that elsewhere are in high-demand and therefore give more flexibility to the employee than to the employer (e.g. IT specialist roles).

Now, a typical ingredient of an "externalization recipe" is to that you externalize to cut costs.

Add to that cost cut the need for the new "supplier" to make a margin, and, while existing staff externalized might leave as soon as possible, meanwhile they would be tasked on training new, cheaper hires.

And if you add more subcontracting layers, you keep cutting down.

On the high-end extreme, I remember how a colleague in London from the banking industry (the bank side, not the supplier side) told me in the early 2000s how he had been surprised once to discover that what they paid a 2,000 GBP a day... became just 400 GBP a day for the consultant.

And also in Italy, as a consultant, I was asked between 25% and 60% of the nominal price paid by the final customer (my standard was 20%, while I considered 50% from those that I trained, but paid a retainer, and in my first job I remember that the ratio was approximately 1:10, as net perceived as an employee vs. what was billed to the customer).

But I am talking about the early 2000s: two decades later...

... it is even worse.

For example, in various industries, I heard that the "zero-hours, 12 months exclusive contract" is quite common (called here informally "a chiamata", i.e. called when needed), along with "informal" contracts.

And even for higher-ranking roles, I read requests from Italy such as one asking... to have somebody acting as the CEO "alter ego", available 24/7, but working as a freelance, and paid only the hours worked.

While in higher-paying roles this might be annoying, but anyway access to market is based more on connections that anything else (i.e. could not bypass all those filters), in lower-paying activities this creates a conundrum.

Recently in Italy political parties mainly from the centre-left started a campaign to set a legal threashold for the minimal hourly rate: as a constant voter for that political side since I was 18, I wonder (tongue-in-cheek) why, while being on and off government for the last two decades, those same politicians never did anything in that direction, and had to wait for a government from the right-of-centre to do it.

The leading industrialists' association replied that companies within their association have a minimum hourly rate that exceeds the proposed one.

Still, some statistics showed by various parties report that few million workers in Italy are below the new proposed threshold of 9 EUR.

As you probably know, I am used by inclination and experience to look at a systemic perspective, i.e. considering all the factors involved (or as many as feasible).

The title of this article refers to the "human side of supply chains".

Part of those few millions working working for less than 9EUR/h are probably focused on services to final customers, and any hourly rate increase could be transferred to customers- up to a point (for some services, increasing the price would make them less accessible).

The widespread use of de-facto multiple levels of subcontracting would imply that some less knowledge-intensive activities are actually used to lower the cost of ensuing higher-paying activities.

Therefore, just increasing the hourly rate would have a certain political value, but an uncertain practical value- unless whole supply chains are revised.

As an example, even those political parties sponsoring the law, are they certain that within their suppliers (and the suppliers of their suppliers) the hourly rate currently applied is 9EUR/h or more? And that they would be able to have the same level of service if prices were revised?

In Italy, since 2012 I saw many cases of what we call in Italian "battaglie identitarie", i.e. having lost ideology, identify something that can be a "banner" to rally your supporters behind, without considering the overall picture.

Interestingly, since the late 1970s (when I started being actively interest in politics), in Italy we had many cases of political parties and related that presented themselves as "different from the others, a new way of doing politics" (yes, like the "none of the above" within the 1998 movie "Bulworth").

Curious how then Partito Radicale, Lega, Italia dei Valori, Cinquestelle became then highly identified with a single, individual leader.

And curious how now, in 2023, a political party that started highly identified with its founder, Berlusconi, is instead becoming associated with multiple members of the structure of the party.

Equally curious how, a party born on the ashes of the former Communist party and components of the former Christian Democrats, the Partito Democratico, i.e. starting with structure and party bureaucrats or second-line politicians from both, now is turning into round after round of identification with the leader.

Some joke that Renzi became few years ago party secretary courtesy of "open primaries" that allowed non-members to cast their vote, and therefore this allowed Berlusconi to select his opponent.

Frankly, I went to vote for Renzi in those primaries, paid my 2EUR, because while I disliked some elements, considered that would be useful to have a reformist at the helm of centre-left: had had enough of a centre-left whose only cohesion element was to be against Berlusconi.

And no, I never voted for Berlusconi.

Others would equally joke that Schlein, the current secretary of Partito Democratico, has won the open primaries- but, this time, she is the preferred candidate chosen by... Cinquestelle.

When you cannot define a political platform, you just pick up from newspapers whatever is trendy today- and e.g. the announced political event from most of the opposition parties, to be held on Saturday November 11th, kept getting day after day a new "reason to be there on the 11th is..."

I know that many Italians dislike even the concept of a "Commissione Parlamentare", i.e. a sitting panel at the Italian Parliament focused on a specific theme or reform: but, frankly, I think that the battle for the minimum hourly wage of 9EUR/h is currently yet another "battaglia identitaria" that has not been considered properly- as if planting the flag were more important than change.

I am still the boring bipartisan reformist from the left that was in the late 1970s (in my youth, being called a "reformist" was an insult, on the left of the political spectrum)- back then I played piano, and said that I wanted to change the music, not just switch the players.

Hence, if really we want to introduce a minimum hourly wage in Italy, probably would need to revise the whole "human supply chain"- just saying that main contractors are above that threshold is not enough, if then all those outside work with "zero hour" contracts or similar concoctions where they are committed full-time, but paid only time that is considered working time, or paid as freelance at a real hourly rate below that, or even (another Italian favorite) paid as "shareholders" of a co-op.

Or: fine the minimum hourly rate, but then revise also all the loopholes that allow to circumvent even existing contracts.

Otherwise, it is just yet another bit of propaganda.

And this brings the next section: what would be needed to raise the bar and quit doing a bit of reform here, a bit of reform there, while missing the whole picture and creating more loopholes?

Also, we should think longer term, as Italy (and not just Italy- most of the EU) is getting older and older.

It takes more than a village

The Italian economy still has a significant slice of smaller companies and "informal" activities, where at least part of the personnel is not officially employed.

While living in Turin during a mission 2015-2018, routinely heard from university students that they were working in cafés, restaurants, etc for a salary that was nominally more or less the same that I had in my first job in 1986: 600EUR- not full-time, but still more than the 66 hours that would be possible at 9EUR/h.

As for the other side of "informal", e.g. people converting magically into customers whenever there was a control, probably unless there is a step-up in controls, they would not bother- and the only check would be assessing how many people would be needed to serve a number of tables that... would require those that suddenly disappeared.

Would all those jobs still be sustainable, if were to move to 9EUR/h?

Doubtful- unless transferred at least part of the increase to prices, and, in other industries, unless there were to be an increase in automation in all the activities that can be converted in this way.

In other countries, Trades Unions sit on the board of companies- which implies developing abilities and skills that go beyond the mere representation and presentation of requests, i.e. developing abilities to be a counterpart with a level of domain knowledge close to that available to management and owners of their counterparts.

This would require a different kind of management, and a different kind of Trades Unions, as in Italy actually one of the issues is that both companies and Trades Unions do not have a long-term orientation, as shown by the "evolution" that observed in contracts from the 1980s until the early 2020s.

I shared in the past how, few years ago, a company such as Leonardo said that they actually worked to help their local suppliers grow the capabilities to be able to become suppliers elsewhere- including of their competitors.

The rationale? In manufacturing within a data-centric society, you need to be able to foster innovation, and fostering innovation requires being able to avoid a tunnel vision, and develop and test new ideas- which requires working in different environments.

So now the focus in Italy in from one side on increasing salaries to a minimum hourly rate of 9EUR/h- but apparently ignoring that this would imply raising the salaries across and therefore raising prices of products and services accordingly, unless there is a significant reduction of the human work within products and services.

In the past the solution has often been delocalizing, but the COVID impact on supply chains showed new significant risks.

The village mentality often is well represent by some attitudes focused on individual companies, while instead, at least larger companies, should grow the ecosystem where their activities are carried out, if they want to be sustainable as a business.

The concept of "sustainable as a business" does not imply just ESGs- implies being able to ensure continuity across the whole supply chain.

Henry Ford was said to have decided to increase the salary of his workers so that they could become customers for his cars.

A national minimum wage is something different- as would increase salaries across the board, and requires restructuring supply chains to ensure that the new cost of work is sustainable at the same price levels.

Also, would require stepping up what has been traditionally the weakest link within the Italian State, as shown by the continuous stream of announces of people dying on their workplace: controls.

Some also discussed in Italy the concept of minijobs as in Germany- this article (in Italian) shares some examples and information, if you are interested.

Anyway, what is the concept of a national minimum hourly wage? To increase salaries for everybody at a minimum level, to avoid creating "working poor", those working full-time but with a salary that does not keep them above the poverty line.

There is another element ignored in many discussions: if our population is getting older and older, we need to reconfigure also the way work is structured.

The first line of this article was: "This article is about what make our 24/7 economy work: people."

To compare using Wikipedia demographic data about Italy, life expectancy in Italy was:

_ 1871 (right after Rome became part of the kingdom of Italy): 29.8 years

_ 1901 (when Italy was still exporting people): 43.5 years

_ 1919 (after WWI): 42.3 years

_ 1946 (after WWII): 59.0 years

_ 2015-2020: 83.3 years.

When I look at processes, activities, and even cities' public transport, I see something still defined by what used to be "normal", a relatively young country, as it was after WWII.

As I wrote in previous articles, a major town such as Turin has now an average age (not just life expectancy) that is over 45 years, and a significant increase in the number of over 80s.

This is expected to further increase- and will imply the need for more people supporting everyday needs.

Which are actually often services that cannot be automated (for now), and where salaries are lower.

As I wrote often, since 2012 whenever I had a mission that required to be in Turin, I lived temporarily in town.

Actually, in 2015, as assumed a long-term mutual interest, became resident in Turin (then shifted away again in 2019).

So, 2012, 2015-2018, 2021-2022, I was in Turin, temporarily or resident, while I had a mission there, and used extensively public transport, while in 2021 also used a coworking (as I had to be remote but based in Turin).

Across a decade, I followed also the changes in labour laws, and often met in various meetups locals, while met others while going around town.

Most of those 20-something to 30-something seem to be fully part of the "gig economy", or switching jobs quite often.

I am much older, but working by mission has been a past choice, while waiting to settle somewhere- while most of those I talked with, also when they have a full-time formally permanent job, never told me of what was common in the 1980s or 1990s even in Italy.

Or: back then, "permanent" meant having also a career plan proposed by your employer.

Most of those I met in their 20s to 30s over the last decade instead are curiously talking about their retiring benefits, while having no visibility of what will happen in the nearer future.

Working in Italy within the "gig economy" or on short-term contracts implies that, when they will be, say, in their mid-60s (when probably they will be allowed to retire), their compulsory contributions would not amount to that much, and it is doubtful that, considering most spending models I saw, they will have resources to have an additional personal retirement fund.

Therefore, they will personal services but would be unable to pay for individual services, in most cases, unless there is a significant restructuring of the way those services are paid and provided.

The title of this article is "The human side of supply chains", and was the obvious starting point for the discussion about the national minimum hourly wage, but actually my purpose was to start from there, and shift to a wider perspective.

In Italy, routinely there is also a discussion about another element, i.e. the "2nd level" labour contract negotiations, at company level.

Anyway, in Italy we have had since a couple of decade a set of structural issues that discussed in previous articles, issues that coupled with a different demographic distribution would require something better than our standard approach to change: tinkering.

Tinkering brought Italy struggling and kicking into the XXI century- but exhausted.

To build a sustainable future, Italy needs a cross-section of society including both the private sector, the public sector, and political as well as private leaders to build and govern a transition that will be anything but smooth.

As I was born in Turin and all my missions in 2012, 2015-2018, 2021-2022 were for a single company in Turin within the automotive industry, I will use what used to be the main industry of Turin as an example of the transition needed.

Worldwide, the automotive industry is doing at least two transitions on the engine side:

_ temporary from fossil-fuel to electric and hybrid

_ long term to a multimode (electric, fuel cell, whatever will be).

At the same time, is shifting from a model based on selling vehicles to another one:

_ aiming to have each vehicle instead of leaving it parked most of the time

_ aiming to generate more revenue from services (e.g. software, on-board entertainment, data, etc).

This could imply at least two results:

_ if most vehicles are going to be shared and not owned, would require a design approach focused on minimizing maintenance and quick part replacement

_ for those vehicles sold, probably will have either to be luxury or for business customers.

Turin used to be the car capital of Italy, a true company town, with many smaller companies that, as I shared in previous articles, were used to work mainly for just one group of companies, those linked to FIAT (Fabbrica Italiana Automobili Torino)- i.e. the company town "owner".

Some small companies eventually entered also the supply chain of other automotive companies, but many really still worked and planned as cog-in-the-wheel for the main customer.

Now that many of the companies belonging to that group changed ownership or could further change ownership (Magneti Marelli became Japanese, FIAT/FCA became de facto French, Iveco was planned to be spinned off by the CNH CEO few years ago to be potentially sold, and was spinned off in 2022), also the relative "weight" of automotive within Italy has been shifting elsewhere.

Still automotive is important in Turin and the surrounding areas, and the first transition (from combustion engine to electrical) is already creating issues- including tens of thousands of jobs within the industry, direct and indirect.

Jobs that pay much more than those in the new, trendy restaurants and café or the "event-based economy" that somebody is presenting as the new manifest destiny of Turin.

The local systemic view is not to jointly manage the transition, but to routinely alternate asking for resources from the State to manage the transition, procrastinating the transition, and...

... self-celebrating the excellence of the territory.

Confirming that for too long the "thinking" was done by those who increasingly are shifting production elsewhere.

And also local politicians seem to be focused on the same pattern: each day asking (not begging: the approach is more one derived from a misguided sense of entitlement) resources from Rome, Brussels, whatever, and each other day self-celebrating successes.

As shared on Facebook tonight about Turin (a newspaper article about Turin's roadmap toward 2050):

" so, few confirmations about #Turin

1. still has the resources needed to shift forward

2. it must just learn to self-celebrate less, invest more on itself

then, once it has shown that local resources are invested locally, could attract others to add their own investments

as, before it decays, it has still human and physical infrastructure and logistics that would be too expensive to build from scratch elsewhere "

Announces and requests from one side and the other will not magically generate what is needed.

They do matter- short-term: but leaders should focus on leaving something better than what they found, not just a long list of minutiae and complaints.

Each one of the main political parties in Italy is currently apparently trying to build a strategy out of such a collection of minutiae, something that could attract voters for the forthcoming European Parliament elections, but the risk is generating more entropy, not reducing it.

Unfortunately, as I wrote above, it seems that in Italy preaching to the choir still takes the lead over identifying and working for a common good- so, be it politicians, industrialists, banks and banking foundations, and all formally non-profit companies seems more interested in evolving their own positioning, by fighting battles for their own courtyard and claiming their own successes.

It takes a village- but a global village.

And it takes the willingness to look at what value can be extracted from the past that could help in positioning for the future, and then tailor a message that is appealing for those whose investments you want to attract.

_

_