Viewed 7650 times | words: 4405

Published on 2020-11-18 08:00:00 | words: 4405

This article... is actually the first of a short series.

Obviously, it is about data- but it is also about democracy and integrating different perceptions of reality into a coherent and cohesive definition of a target reality.

This is just an introduction, and therefore will share some background doubts, more than background ideas.

I will quote examples from Italy, but, frankly, the content of this series applies also to other countries.

Our belonging to shared institutions (e.g the European Union, but also OECD and WTO) that have impacts on what is considered acceptable from a regulatory perspective implies that we aren't just converging.

We are actually cross-feeding between countries also laws and regulations.

We live in a world where data are continuously quoted, and, courtesy of COVID-19, we can hear talks about statistics from the most unexpected quarters- on a daily basis.

Apparently, the level of "numeracy" on Facebook has been boosted by COVID-19.

Well... apparently.

So, it reminded me an old story- few days ago shared on Facebook a post on a funny joke/story, about when a company aiming to compete with McDonalds started offering hamburghers larger than the quarter pound variety offered by golden arches.

A catch: the advertisement talked about their own 1/3 vs. 1/4 of McDonalds- but customers were used to see a larger number as a sign of something bigger- hence, 1/3 was assumed to be smaller than 1/4.

I do not know if it is true or not- but, as I wrote not too long ago, when I returned working and living full-time in Italy, I was puzzled as continuously clerks gave me more change that I was entitled to- then and there, I discovered that, instead of talking about increasing STEM training in schools, we should actually improve the basics, as so many young adults, once they leave school, forget everything they learned, even the basics.

So, imagine now that newspapers are, on a daily basis, talking about statistics, probability, Rt, and all the paraphernalia of epidemiology.

Not that scientists and other experts, suddenly interviewed by newspapers and TVs, retained necessarily their old, boring, slow way to check and double check, and then meta-check... what had been checked by others.

Bystra is a village in Poland- but also a word in Russian that has the same meaning- it is fine if applied to a "Bistrot" (yes, ante-litteram fast-food, but also in Pompei there were "street food" places, in Ancient Rome).

Incidentally: from the wikipedia page, the village in Poland looks nice, and it has a quite interesting story, being almost at the corner of three countries. No, I never visited it- simply, I did not know it existed until I checked online if I could write a quip on "bystra"- sheer multilingual luck!

But applied to science that potentially has impacts on decisions taken by politicians and administrators impacting on millions of people? Doubtful.

I shared two days ago privately my doubts about the announce that COVID-19 was going around Italy in summer 2019 (!), when the series of tests was presented, and yesterday morning I heard an epidemiologist tearing apart the method, tools, approach, and the same today on newspapers.

The lesson, repeated at least a dozen times since March 2020 on COVID-19, is: do not overrate a single study, single method- I will leave to others more qualified (and equipped with a budget) to do a meta-study (if feasible) to cross-check the results.

My commentary is just business common sense: would you make critical choices based just on a single source that admittedly did a fast assessment that, despite the media hype, can only be called "preliminary"?

The "scientific debate" in Italy since January 2020 became so much a matter of "celebrity driven science", that reminded me of this documentary on experts and expertise

Why this introduction to the introductory article of the series? Because... this first article is more about doubts than certainties, as I said at the beginning- to build solid foundations of what will discuss, more future-oriented, in the next few articles.

Also, to keep those articles short.

In this introduction, I segmented the doubts into sections:

_ the technocratic risk of data

_ the infallibility dogma

_ the bias of all biases

_ the competency illusion

_ going smart- again

_ what's next

The technocratic risk of data

Yes, we are in a crisis- a crisis that will probably last a while, and whose impacts will last even longer.

In other countries maybe just "health" impacts, in most also "economic", but, frankly, in most democracies there will be a lot to think about.

In Italy? Well, it has been barely a couple of decades since a set of changes to the Italian Constitution expanded the powers of regional governments, and we had already pre-COVID some issues.

The emergency state started in January 2020, followed by some flip-flopping created what personally I repeatedly called "a parallel set" of decision-making circles.

When we would expect coordination, tinkering resulted more than once in regional governments making their own choices by talking horizontally with other regional governments, and then asking the Government to underwrite.

But more often than not, the opposite happened.

Result: few days ago, our three-level color-coded territory (by region) resulted in theory in yellow/orange/red with increasing levels of restrictions, but, in reality, some regions eventually decided to pre-empt and adopt stricter measures than what their color-coding required- a patchwork of measures that might be solved soon, but will hopefully generate food for thought for few PhDs in political science before... the next round of structural reforms.

If anything, in Italy and elsewhere we will need to rethink the ordinary- which, often, wasn't really "ordinary", was simply what we were used to.

Few months ago, on 2020-08-04, shared a short article (for my standards).

I would like to recap here one of the first concepts that contained:

"being able to often connect the dots before even most insiders do, as they and way too many insiders have a "tunnel vision".

In any complex organization (even informal organization), as I often say, a "systemic view" is available often only at the top- formal and informal.

Formal- e.g. for some CEOs, CFOs, CIOs- etc.

Informal- as, the more complex the organization, the more common are, in my experience, some "connectors" that enable to cover the routine timelag between the reality on the ground, and the formal organization.

Anyway, not all those CXXs have a systemic view- others are happy seeing their role as an achievement, letting others be their "vertical" filter toward reality, and never venture from their castle in the sky à la Magritte."

Yes, tunnel vision: and, frankly, as I routinely write in my commentary on local news (have a look on Facebook and Linkedin), way too many people in a crisis cling to what they know, and try to ignore reality, if that brings them outside their comfort zone.

In ordinary times, you have time and resources to chase your own tail before confronting reality, but in a crisis, moreover with a virus such COVID-19 (or, before it, e.g. the Spanish flu of 1918), tinkering your way out of the hole that you yourself have been digging is not advisable.

Hence, the title of that article was... Making it simpler? Italy, the externalization country, needs more transparency.

Now, over the last few days saw that at last I wasn't anymore one of the few stating that we need to collect minds, not balance powers, i.e. we need a new "Costituente": "Instead, what we need now is to build something thinking about structural changes that will affect (and, in most cases, paid by) future generations- exactly as it was after WWII with the "Costituente" (elected on purpose to write the Italian Constitution)".

As you probably know, on the "technical" side of my business activities (the other side was of course the "human" side, cultural and organizational change, but also negotiations, coordination, etc), I have been dealing with data and number crunching for business managers since the 1980s.

Now, having started to work in information technology in 1986 but after first political activities first, then sales to people, then serving in the army on the bureaucratic side, I have a key difference with my fellow information technology practitioners: I do not see information technology or data (or any kind of expertise) as "neutral".

I know that this is a debate as old as documented human history, but I would like to restrict to my personal business experience since the 1980s.

Choosing which data to consider is a business-political choice: you do not collect everything everywhere.

The infallibility dogma

Despite what some "big data" enthusiasts say, if instead of talking of "philosophy of data" they were to read a little bit more on the history of philosophy, they would have to acknowledge that, no matter how "big" your data pile is, it is never going to be "all the data"- but always "all the data that you decided to collect" (or that you decided that it was worthwhile to produce so that you could then routinely "harvest").

Which implies e.g. setting up systems (people, processes, technologies) to collect those data.

Then, the longer your go down your knowledge supply chain in moving from "data" to feeding morsels to decision makers, the more assumptions are done- and not necessarily communicated with an appropriate level of transparency.

Appropriate level of transparency, in my view, implies "understandable": just because you release hundreds of pages of formally correct data analysis and tables or charts, does not imply that its nuances are understandable to those that will need that information to make choices.

Sometimes this is intentional- as I was reminded in the 1980s when I was told that, as analysts following a company were "allocated" by agencies, a trick-of-the-trade was to produce annual reports that were exactly the same year after year, with tiny details, and nuances scattered in footnotes: used to read and see always the same pages, in many cases some changes were ignored.

And just yesterday was reminded that e.g. Enron, just before failing, had received prizes for its... code of conduct. True or false, it is now a collectors' item, and can fetch a decent price on ebay- you can read some fascinating quotes here.

I am obviously for more data, but only if there is more transparency about their "journey" from source to destination- otherwise, "data technocracy" is yet another form of "infallibility dogma".

And, in a democracy, there should not exist such a thing: anybody is fallible, and any decision has to be contextualized (e.g. time, resources, constraints, choices), and maybe reversed (within physics constraints, of course- albeit Italian politics pre-dates Schroedinger cat in allowing multiple possibilities).

If, for example, I say that I am (as I am) resolutely against the death penalty, I can justify that with data- but then, it is a political choice.

And it is a political choice to keep saying: no, I do not consider reversing my position- I am against death penalty, as well as I am against any form of torture.

Hence, when I was in the Army (just one year of compulsory service), as I was against the concept called in Italian "nonnismo" (i.e. a kind of informal hierarchy based on seniority, that resulted in routine humiliation of those who had just arrived by those who were about to end their 12 months of service, and tolerated by weak officers that weren't leaders, as a form of informal control structure), when it was my turn to be "senior", I explicitly fought against it (I shared in the past that some of the side-effects included a target "designed" with a bayonet on my bed linens, plus some other threats).

What matters is: if you make a choice based on data supporting your position, then when you make your choice, you should not simply hide behind the data as an excuse.

Now, if your choice is based on temporary information, not a matter of political and moral choice, you have to keep your mind open to the possibility that you will have to reverse choice.

Hypocrisy is changing your mind just because this changes the benefits that you can extract, not changing your mind because what helped you make the original choice changes.

But, if you accept my initial proposition that any data is "selective", no matter how "big", it is relatively straightforward to accept that, unless you assume to be a god that has perfect knowledge...

...human fallibility implies that, once a decision is made, and data supporting that decision are selected, you will keep being inclined to see those data that confirm your choice.

Therefore, you will need to accept an external, continuous, independent "reality check" as a safeguard.

The bias of all biases

Somebody would say that technology, e.g. Artificial Intelligence, will remove the issue, by creating "neutral" expertise.

Do you remember the movie "Blade Runner", the one from the novel "Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?".

Well, a quip about one of the most famous datasets used for image recognition is that... models that "learned" from it are inclined to think about dogs whenever they "see" images that are unexpected.

Reason? It contains a relatively larget subset of images of various breeds of dogs- helping to achieve expert-level recognition of dogs, but influencing, in case of unknowns, to default to dogs.

Before my more technically-oriented readers start thinking about rebalancing the dataset: sorry, that wasn't the point.

The point is that also a large dataset can be biased despite all the best intentions, as any human activity is, unfortunately, biased.

Why? Again: because we do not have perfect knowledge and infinite time.

Therefore, here and there we take various "shortcuts"- it is what helped us to survive, adapt, thrive as a species.

If our ancestors had decided to overthink every choice by trying to collect all the knowledge available, and then sort out what influenced to extenuating details... they would have either starved to death, or become the meal of some larger predator that they actually went out hunting for food and wasn't that much interested in the philosophy of hunting.

We are pretty much a trial-and-error species.

When I was spending my vacation time at LSE in the summer of 1994, my American professor asked if I was a critic of democracy: well, I would like people to take more seriously their right to vote.

Democracy, in my view, requires an initial investment from each citizen in at least the basics- but this is, frankly, what should be delivered by the national school system (I know, my position is not necessarily popular).

Then, it takes a continuous investment- which is in keeping informed and feeding a critical mind, not just flash-mobbing your way into "herd mentality" (which can temporarily result in positive outcomes, but long-term undermines democracy, as generates yet another self-appointed "lord of the flies").

So, I am neither an elitist who thinks that only those who invest time in learning the mechanics should be entitled to active and passive vote, nor a populist who thinks that citizenship per se generates active and passive voters.

In my view, as in other fields, it is a matter for the State to ensure equal opportunities- by giving the basics to everybody.

Which, in the XXI century, is something more than just being able to read and write.

As I shared above, but it is worth repeating, I shared online how often, since returning in Italy working full-time in 2012, I was amazed of how often I was given in shops exchange in excess, and sometimes, when I explained the mistake, I was even looked with a puzzled sight on the face as if I were trying to explain rocket science.

Ditto for what I consider the bread-and-butter of real literacy, i.e. being able to understand not just what the text says, but also the purposes of the author(s).

To say nothing about the perception of "reality as presented by social media" (and, often, by traditional media, too- in hurry to compete with social media, I see increasingly more "made" than "reported" news).

The competency illusion

If you are reading this post, probably you read my previous posts were routinely I lambast our obsession (and not just in Italy) for "leaders"- that actually we confuse with a demi-god who takes off our shoulders the need to think and choose, specifically the "charismatic leader".

In our post-industrial times, we have another quixotic myth of democracy that I equally displease: that of "electing the competent".

My usual quip, in Italian, is "competente in che cosa?"- i.e. you should qualify "competency".

Again, we are humans, so our time to acquire knowledge and experience is limited- anybody assuming to have all the knowledge is either delusional, or just a fraud.

There is always a risk that you can observe each and everyday on any talk show on any TV in any country in any Western democracy: we get somebody competent in A, package with a charismatic leadership aura, and, pronto, here you have somebody who can talk about anything anytime to anybody "with competence"- and all this never bothering to acquire any competence beside the one that originally (supposedly) had.

Well... pretended to have, in my view. Being, say, the most qualified heart surgeon, does make you the most qualified surgeon general? Or will you, anyway, have to rely on the advice of other specialists, say, those with a specialist knowledge in epidemiology or biochemistry, or the administrative and policy side of health?

And this leads to another danger for democracy in a post-modern era.

Let's just say that our societies are too complex to be really managed by a single individual.

I think that nobody would question that- then, why do we obsess with "electing competents/incompetents"?

Even a small village, nowadays, has to comply with and oversee compliance with so many laws and regulations (notably in Italy), that there is limited chance that can do so "with competence".

Even the most competent individual will either stick to what (s)he knows (a case of "if your only tool is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail"), or do "how was done in the past".

In reality, to access all the benefits that a complex society generates through standardization and pooling of resources, even the smallest village would not need somebody "competent", but somebody "competent in finding those competent, and in being kept informed of new developments".

Going smart- again

Yes, I wrote a couple of articles recently where the first part of the title was the same that I used for this section- talking about smartwork, smartcities, smartvehicles, and focusing on Turin and Italy as examples (you can read part1 from 2020-08-24 and part2 from 2020-10-01)

Anyway, for this short series I will try to keep each one of the future articles as short as possible, shifting deeper discussions (and sharing associated data and ideas inspired by the data) to future publications.

To keep a long story short: yes, data are needed to "go smart": it is a matter of informed choices.

Making choices just on intuition might be fine if you are alone and what you do has impact on nobody else.

In a complex society, you should think also about impacts.

And the wider your potential impacts (e.g. because you are making choices not just for yourself, but for thousands or millions), the more your choices should involve all the "competencies" that might make your choice an informed choice.

Or a good approximation thereof.

There will always be an element of uncertainty- but there is a not-so-subtle difference between using incomplete information to make your choices (i.e. taking risks) and using no information, or letting your biases guide your choices.

The latter was well represented by Barbara Tuchman in her "The March of Folly", "the pursuit by governments of policies contrary to their own interests" (if you are unwilling or unable to read the whole book, you can find a summary on wikipedia, along with links to book reviews).

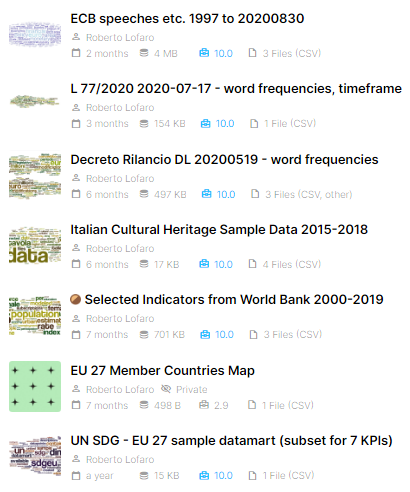

As I did since October 2019 on my Kaggle profile, and previously by including some data analysis within articles, I will keep sharing data that are actually going to be part of my future publications, so that, without waiting for my longer scribblings (a.k.a. mini-books, e.g. see those published since 2012, maybe somebody else will be able to contribute to (and maybe refute) some ideas- saving time to us all.

My approach to data is the same I used in business since 1988 whenever I had to find or extract information from sources to define new KPIs or other representations to monitor the evolution of activities.

If you define that your timeframe of interest is "from now on", these are the criteria:

1. should be foreseen a routine update by the source, if needed

2. are considered non-partisan (i.e. do not represent a specific agenda, and therefore could be more acceptable as components to indicators to both political activists and business advocates)

3. each indicator should be provided by a "domain expert source" and then collated by an acknowledged "super-partes" (again, to improve credibility and perception as non-biased)

4. last but not least: each indicator should be useful, alone or with others, to help set an agenda for action (e.g. used the indicators on access to Internet, workforce inclusion, urbanization, etc).

So, personally, after I found the COVID-19 dashboard that suited my information needs, I did not bother with joining the data science "COVID-19 dashboard vanity fair" and create my own using Shiny or other tools.

As an example, these are the criteria that I adopted to select, between hundreds of indicators within the WorldBank data, 33 that I deemed useful to my purposes (writing about business and social change while considering digital transformation and its impacts).

If interested, have a look at the "description" and "metadata" section on each one of the files that I shared on Kaggle:

You can find here a short description, release date, next update planned, as well as a link to the Kaggle dataset (where I posted both the files in CSV format, as well as Jupyter Notebooks in either R or Python with basic information, but will add proper analysis whenever I will reuse the data within a publication), and any other online material associated with each dataset.

What's next

Well, I did not talk that much explicitly about "systemic thinking", and therefore... you can read more about that in another recent article where, as in the one on 2020-08-04 that I quoted at the beginning of this article, discussed a typical italian issue that interferes with much-needed (notably in a crisis) systemic thinking, our "tribal orientation".

The article was COVID-19 : systemic impacts and parochial thinking- moving toward long-term sustainability, posted on 2020-09-01.

Now, what will be next in this series?

Few short articles, this time focused on industry (automotive/mobility, insurance/banking/financial) and the element that will aggregate, in one form (physical) or another (virtual) most of the population in industrialized countries in the XXI century, smartcities.

Because I strongly disagree with those who say that COVID-19 will kill urbanization: but I will share my view on this subject later.

The focus of the next articles in this series will be Italy, and therefore each article will have a title starting with "Going smart (with data): the Italian case".

At the end of the series, will share another publication element discussing the previous articles within the series vs. what was presented in the first version of the "Decreto Semplificazioni" presented by the Italian Government during summer 2020 (it was about streamlining the Italian State, and was part of the initiative to build proposals for the Next Generation / Recovery Plan).

Why the first version and not the latest? Because the first is a certainty, the others will evolve.

Stay tuned!

_

_